Jack Keil, executive creative director of the Dancer Fitzgerald Sample ad agency, was stuck in a Kansas City airport at three in the morning when he started thinking about Smokey Bear. Smokey was the furred face of forest fire prevention, an amiable creature who cautioned against the hazards of unattended campfires or errant cigarette butts. Everyone, it seemed, knew Smokey and heeded his words.

In 1979, Keil’s agency had been tasked with coming up with a campaign for the recently-instituted National Crime Prevention Council (NCPC), a nonprofit organization looking to educate the public about crime prevention. If Keil could create a Smokey for their mission, he figured he would have a hit. He considered an elephant who could stamp out crime, or a rabbit who was hopping mad about illegal activity.

A dog seemed to fit. Dogs bit things, and the NCPC was looking to take a bite out of crime. Keil sketched a dog reminiscent of Snoopy with a Keystone Cop-style hat.

Back at the agency, people loved the idea but hated the dog. In a week’s time, the cartoon animal would morph into McGruff, the world-weary detective who has raised awareness about everything from kidnapping to drug abuse. While he no longer looked like Snoopy, he was about to become just as famous.

In 1979, the public service advertising nonprofit the Ad Council held a meeting to discuss American paranoia. Crime was a hot button issue, with sensational reports about drugs, home invasions, and murders taking up the covers of major media outlets like Newsweek and TIME. Surveys reported that citizens were concerned about crime rates and neighborhood safety. Respondents felt helpless to do anything, since more law enforcement meant increased taxes.

To combat public perception, the Ad Council wanted to commit to an advertising campaign that would act as a preventive measure. Crime could not be stopped, but the feeling was that it could be dented with more informed communities. Maybe a clean park would be less inviting to criminals; people might need to be reminded to lock their doors.

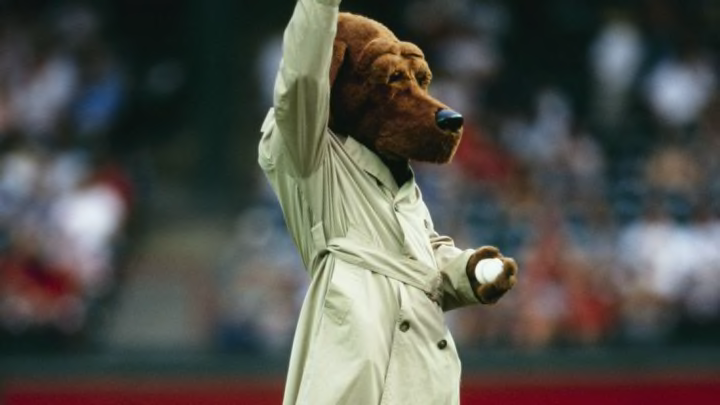

What people did not need was a lecture. So the council enlisted Dancer Fitzgerald Sample to organize a campaign that promoted awareness in the most gentle way possible. Keil's colleagues weighed in on his dog idea; someone suggested that the canine be modeled after J. Edgar Hoover, another saw a Superman-esque dog that would fly in to interrupt crime. Sherry Nemmers and Ray Krivascy offered an alternative take: a dog wearing a trench coat and smoking a cigar, modeled in part after Peter Falk’s performance as the rumpled TV detective Columbo.

Keil had designs on getting Falk to voice the animated character, but the actor’s methodical delivery wasn’t suited to 30-second commercials, so Keil did it himself. His scratchy voice lent an authoritarian tone, but wasn't over-the-top.

The agency ran a contest on the back of cereal boxes to name the dog. “Sherlock Bones” was the most common submission, but "McGruff"—which was suggested by a New Orleans police officer—won out.

Armed with a look, a voice, and a name, Nemmers arranged for a series of ads to run in the fall of 1980. In the spots, McGruff was superimposed over scenes of a burglary and children wary of being kidnapped by men in weather-beaten cars. He advised people to call the police if they spotted something suspicious—like strangers taking off with the neighbor’s television or sofa—and to keep their doors locked. He sat at a piano and sang “users are losers” in reference to drug-abusing adolescents. (The cigar had been scrapped.)

Most importantly, the NCPC—which had taken over responsibility for McGruff's message—wanted the ads to have what the industry dubbed “fulfillment.” At the end, McGruff would advise viewers to write to a post office box for a booklet on how to prevent crime in their neck of the woods.

A lot of people did just that. More than 30,000 booklets went out during the first few months the ads aired. McGruff’s laconic presence was beginning to take off.

By 1988, an estimated 99 percent of children ages six to 12 recognized McGruff, putting him in Ronald McDonald territory. He appeared on the ABC series Webster, in parades, and in thousands of personal appearances around the country, typically with a local police officer under the suit. (The appearances were not without danger: Some dogs apparently didn't like McGruff and could get aggressive at the sight of him.)

As McGruff aged into the 1990s, his appearances grew more sporadic. The NCPC began targeting guns and drugs and wasn’t sure the cartoon dog was a good fit, so his appearances were limited to the end of some ad spots. By the 2000s, law enforcement cutbacks meant fewer cops in costume, and a reduced awareness of the crime-fighting canine. When Keil retired, an Iowa cop named Steve Parker took over McGruff's voice duties.

McGruff is still in action today, aiding in the NCPC’s efforts to raise awareness of elder abuse, internet crimes, and identity theft. The organization estimates that more than 4000 McGruffs are in circulation, though at least one of them failed to live up to the mantle. In 2014, a McGruff performer named John Morales pled guilty to possession of more than 1000 marijuana plants and a grenade launcher. He’s serving 16 years in prison.