By fusing two imaging techniques, researchers at Northwestern University have illuminated ancient Roman texts that had been hidden inside the binding of another book since the 1500s.

From the 1400s up until the 1700s, it was common for book binders to recycle parchment to create new books, leaving behind fragments of text from the original book hidden within the bindings. While researchers are aware that these hidden texts exist, they cannot be viewed without destroying part of the books.

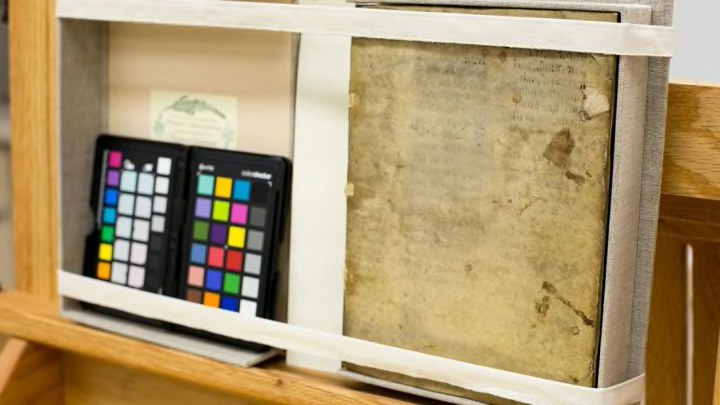

The book at hand, a 1537 copy of Works and Days by the Greek poet Hesiod, has been at Northwestern since 1870. The book still contains its original binding, and researchers studying it noticed still-visible writing on the book board that the book binder had clearly tried to wash or scrape away. The board was covered with a parchment cover, but the ink had degraded the parchment over the years, so that the writing began to peek through.

They sent the book to Cornell University to be examined by a powerful, high-intensity x-ray called the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source, or CHESS. The x-ray revealed text that a historian identified as a piece of the 6th-century Roman legal code Institutes of Justinian, with notes and analysis written along the margins.

However, the researchers hoped to create a way to image similar books without sending them to another institution for analysis. Other scholars might not have the resources to send their books off for study, and some books are too delicate for travel, anyway. They wanted to find an in-house way to come up with similar results.

They began by using two different imaging techniques. One, using macro x-ray fluorescence, is sensitive to the metal in the ink, so it provides good contrast in an image—but it also has poor resolution and is a slow process. The other, using hyperspectral imaging in the visible range, is faster and offers good spatial resolution, but lacks contrast. "Using these two techniques alone, we could not read the text," study co-author Emeline Pouyet tells Mental Floss.

That's when they used a machine-learning algorithm to discover that by "fusing the data" from the techniques, they could create an image of the text that was nearly as readable as the one produced at Cornell. That means "we can use these instruments on site and analyze similar collections using this approach," says Pouyet.

The authors published their results in the August edition of the journal Analytica Chimica Acta.

The technique could yield many more finds within the recycled bindings of medieval books. "We've developed the techniques now where we can go into a museum collection and look at many more of these recycled manuscripts and reveal the writing hidden inside of them," explains co-author Marc Walton, of the Northwestern University-Art Institute of Chicago Center for Scientific Studies, in a university press release.