Winston Churchill called it "the first world war." Fought between 1754 and 1763, the misleadingly named Seven Years' War (often called the French and Indian War in North America) pitted Europe's major colonial powers against each other in theaters across the globe, from North America and Africa to India and the Philippines. On one side of the conflict stood Great Britain and its allies, including Portugal and German states. The other camp was led by France, whose comrades included Russia, the Holy Roman Empire, and Spain.

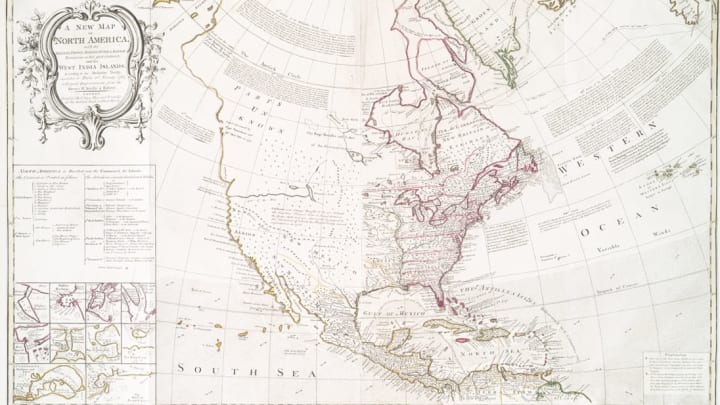

In the end, Great Britain prevailed. On February 10, 1763, representatives from Britain, France, Spain, Hanover, and Portugal met in Paris to sign a peace treaty. Few documents have shaken up global politics so dramatically. This Treaty of Paris wrested Canada from France, redrew North American geography, promoted religious freedom, and lit the fuse that set off America's revolution.

1. THE TREATY HANDED CANADA TO BRITAIN—A MOVE ENDORSED BY BEN FRANKLIN AND VOLTAIRE.

Before the war ended, some in the British government were already deciding which French territories should be seized. Many believed that Great Britain should annex Guadaloupe, a Caribbean colony that produced £6,000,000 worth of exports, like sugar, every year. France’s holdings on the North American mainland weren't nearly as valuable or productive.

Benjamin Franklin thought that securing the British colonies' safety from French or Indian invasion was paramount [PDF]. In 1760, he published a widely-read pamphlet which argued that keeping the French out of North America was more important than taking over any sugar-rich islands. Evidently, King George III agreed. Under the Treaty of Paris, Britain acquired present-day Quebec, Cape Breton Island, the Great Lakes basin, and the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. France was allowed to regain possession of Guadaloupe, which Britain had temporarily occupied during the war. Some thought France still came out on top despite its losses. In his 1759 novel Candide, the French philosopher Voltaire dismissed Canada as but a "few acres of snow."

2. FRANCE RETAINED EIGHT STRATEGIC ISLANDS.

Located in the North Atlantic off the coast of Newfoundland, the Archipelago of St. Pierre and Miquelon is the last remnant of France's North American empire. The Treaty of Paris allowed France to retain ownership of its vast cod fisheries around the archipelago and in certain areas of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In return, France promised Britain that it wouldn't build any military facilities on the islands. Today, the 6,000 people who live on them are French citizens who use euros as currency, enjoy the protection of France's navy, and send elected representatives to the French National Assembly and Senate.

3. AN EX-PRIME MINISTER LEFT HIS SICKBED TO DENOUNCE THE TREATY.

Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder had led Britain's robust war effort from 1757 to 1761, but was forced out by George III, who was determined to end the conflict. Pitt's replacement was the third Earl of Bute, who shaped the Treaty of Paris to placate the French and Spanish and prevent another war. Pitt was appalled by these measures. When a preliminary version of the treaty was submitted to Parliament for approval in November 1762, the ex-Prime Minister was bedridden with gout, but ordered his servants to carry him into the House of Lords. For three and a half hours, Pitt railed against the treaty's terms that he viewed as unfavorable to the victors. But in the end, the Lords approved the treaty by a wide margin.

4. SPAIN SWAPPED FLORIDA FOR CUBA.

Florida had been under Spanish control since the 16th century. Under the Paris treaty, Spain yielded the territory to Britain, which split the land into East and West Florida. The latter included the southern limits of modern-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and the Florida panhandle. East Florida encompassed the the territory's peninsula. In return, Spain recovered Cuba and its major port, Havana, which had been in British hands since 1762. Twenty-one years later, Great Britain gave both Florida colonies back to the Spanish after the American War of Independence.

5. THE DOCUMENT GAVE FRENCH CANADIANS RELIGIOUS LIBERTY.

French Canada was overwhelmingly Catholic, yet overwhelmingly Protestant Britain did not force religious conversions after it took possession of the territory. Article Four of the Treaty of Paris states that "His Britannic Majesty, on his side, agrees to grant the liberty of the [Catholic] religion to the inhabitants of Canada … his new Roman Catholic subjects may profess the worship of their religion according to the rites of the [Roman] church, as far as the laws of Great Britain permit."

The policy was meant to ensure French Canadians' loyalty to their new sovereign and avoid provoking France into a war of revenge. As anti-British sentiment emerged in the 13 American colonies, historian Terence Murphy writes, Great Britain needed to bring the French Canadians into the fold because they were "simply too numerous to suppress." This provision in the Treaty of Paris probably influenced the U.S. Constitution's guarantee of religious freedom.

6. A SECOND, SECRET TREATY GAVE HALF OF LOUISIANA TO SPAIN.

By the 1760s, the French territory of Louisiana stretched from the Appalachians to the Rocky Mountains. Faced with a likely British victory in the Seven Years' War, France quietly arranged to give the portion of Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, including the city of New Orleans, to its ally, Spain, in 1762. (The rest eventually went to Great Britain.) The deal was struck in the Treaty of Fontainebleu. This arrangement wasn't announced to the public for more than a year, and Britain's diplomats were completely unaware that it had taken place while they negotiated the Treaty of Paris. By ceding so much territory to Spain, French foreign minister Étienne François de Choiseul hoped to compensate that country for its forfeiture of Florida.

7. CHOISEUL PREDICTED THAT THE TREATY WOULD LEAD TO AMERICAN REVOLT.

Before the Treaty of Paris, the threat of a French Canadian invasion had been keeping Britain's colonies loyal to the crown. When Canada became British, king and colonies no longer shared a common enemy, and the colonists' grievances with Britain came to the fore.

Choiseul predicted this chain of events, and saw it as an opportunity for France take revenge on Britain. Before the Treaty of Paris had even been signed, he'd started rebuilding France's navy in anticipation of a North American revolt. He also sent secret agents to the American colonies to report signs of growing political upheaval. One of these spies, Baron Johan de Kalb, later joined the Continental Army and led American troops into numerous battles before he died in action in 1780.

8. THE TREATY HAD A MAJOR IMPACT IN INDIA.

In the early 1750s, the British East India Company and its French counterpart, the Compagnie Française des Indes, clashed regularly over control of lucrative trade on the Indian subcontinent. Once the Seven Years' War began, this regional tension intensified. France's most vital Indian trading post was the city of Pondicherry, which British forces captured in 1761.

The Treaty of Paris returned to France all of its Indian trading posts, including Pondicherry. But, it prohibited France from fortifying the posts with armed troops. That allowed Britain to negotiate with Indian leaders and control as much of the subcontinent as it could, dashing France's hope of rivaling Great Britain as India's dominant colonial power.

9. IT TRIGGERED A HUGE NATIVE AMERICAN UPRISING.

For decades, French leaders in the eastern Louisiana Territory had developed alliances with native peoples. However, when that land was transferred to the British, some Native Americans were shocked at the French betrayal. Netawatwees, a powerful Ohio Delaware chief, was reportedly "struck dumb for a considerable time" when he learned about the Treaty of Paris. In 1762, the Ottawa chief Pontiac forged an alliance between numerous tribes from the Great Lakes region with the shared goal of driving out the British. After two years, thousands of casualties, and an attack with biological weapons, Pontiac and representatives of Great Britain came to a poorly enforced peace treaty in 1766.

10. THE TREATY CAME TO AMERICA AFTER 250 YEARS.

Once the Treaty of Paris was signed in that city, it stayed put. In 2013, the British government lent its copy—the first time the document would be displayed outside Europe—for an exhibit in Boston, Massachusetts, commemorating the 250th anniversary of the signing. The Bostonian Society's "1763: A Revolutionary Peace" exhibited the document alongside other artifacts from the Seven Years' War. Afterward, the manuscript returned to Great Britain.