J.S. Allen sensed trouble in the air. It was September 7, 1876, and the Northfield, Minnesota hardware store owner had noticed three mysterious men loitering in front of Lee & Hitchcock Dry Goods Store, right next door to the First National Bank—a strange mid-afternoon scene for the small town's main street.

Once the suspicious trio rose and entered the bank, Allen decided to investigate the scene for himself. Little did he know he'd soon be staring down the barrel of a gun wielded by a member of the infamous James-Younger Gang.

Clell Miller, along with Cole Younger, had been standing guard for the surprise heist. As Allen approached the bank, Miller grabbed his collar. "You son of a b****, don't you holler," Miller growled, pointing his revolver at Allen.

Allen managed to squirm free from the bandit's grasp. He raced around the corner, yelling, "Get your guns, boys; they're robbing the bank!" The people of Northfield heeded Allen's call to arms and grabbed their weapons. Amid a flurry of bullets, the James-Younger Gang was suddenly outnumbered. The incident would go down in history as the Wild West's most famous failed bank robbery, and would indirectly leave a much longer legacy: the founding of the longest-running penal newspaper run solely by inmates.

The James-Younger Gang was a hardscrabble band of Confederate guerillas-turned outlaws, led by brothers Jesse and Alexander Franklin "Frank" James and siblings Cole, Bob, and Jim Younger. During the latter half of the 19th century, the men became household names as they held up trains, robbed banks, and generally terrorized the West, from Texas to Kentucky to their native Missouri.

Of the eight gang members who took part in the Northfield robbery, three had ridden into town ahead of the others. Before their arrival, Cole Younger later recounted, these men had split a bottle of whiskey. The faction had been told to wait for backup before entering the bank, but they reportedly disregarded this command. As the trio saw the other five gang members approaching, they barged into the bank too early. "When these three saw us coming, instead of waiting for us to get up with them they slammed right on into the bank regardless, leaving the door open in their excitement," Cole wrote in his memoirs.

Inside the bank, the trio clumsily fumbled through the motions as they ordered acting cashier and town treasurer Joseph Heywood to open the safe. (Later, a bank teller would recall that he smelled liquor on the men.) Heywood told the robbers that the safe's door had a time lock, and could only be opened at a specific time.

But after Allen interrupted the robbery, the James-Younger Gang's days were numbered. As a gunfight erupted on the street, Cole rode to the bank and yelled for the three to hurry and get out. One member shot Heywood in the head, killing him, and both Miller (the one who'd assaulted Allen) and bandit Bill Chadwell died in the standoff outside. The rest of the gang were wounded, with the exception of the James brothers. Against the odds, the surviving bandits managed to flee town—but their freedom wouldn't last long.

A search party apprehended the three Younger brothers, along with a gang member named Charlie Pitts, close to the Iowa border. Pitts was killed in the ensuing standoff. Only Jesse and Frank James made it out.

Jesse James would go on to recruit new outlaws and continue his life of crime. He'd die six years later in 1882, at the hands of fellow gang member Robert Ford, and Frank James would turn himself in shortly after his brother's death, eventually living out the rest of his days performing odd jobs ranging from burlesque ticket taker to a berry picker before returning to his family farm in Missouri (though Frank spent some time in jail, he was acquitted on all charges and never served time in prison). But for all intents and purposes, the cabal of ruthless robbers was no more.

In November 1876, the Youngers pleaded guilty in court to escape a near-certain death penalty. They were sentenced to a lifetime of hard labor at the Minnesota State Prison. (The facility no longer exists; in 1914, it was replaced by the Minnesota Correctional Facility–Stillwater in neighboring Bayport [PDF].)

At the Minnesota State Prison, inmates were leased as laborers for private businesses. They worked nine to 11 hours each day and were paid a daily salary of 30 to 45 cents. Prison seemed to have a sobering effect on both Cole and the other two Youngers, and they eventually received more prestigious jobs: Cole was made the prison's librarian; Jim became the "postmaster," who delivered and sent inmates' approved letters; and Bob worked as a clerk.

Then, nearly a decade into their sentence, the three became newspaper founders, thanks to another prisoner named Lew P. Shoonmaker (or Schoonmaker).

Many key facts about Shoonmaker have been lost over the years, although the Minnesota State Archives did recently re-discover his prison records. They note that Shoonmaker was a onetime bookkeeper from Wisconsin who was sentenced to a two-year term in 1886 for forgery. He was released in August of the following year for "good conduct," and a remark in an 1887 newspaper indicated that he went on to edit a paper in Waupun, Wisconsin. But earlier in 1887, while still incarcerated, the enterprising inmate approached Cole Younger and told him that he wanted to launch a prison publication.

The paper was to be the first in the nation to be funded, written, edited, and published entirely by inmates. And after several months of trying to convince the prison's skeptical warden, Halvur Stordock, to approve the publication, Shoonmaker had finally received the go-ahead. Now, all he needed were willing investors—and he wanted Cole to be one of them.

The deal would benefit both men. Shoonmaker would sell more papers if a notorious name like Cole Younger's was attached to the project. And Younger was likely intrigued by the plan's business model, which would ultimately funnel money directly into the prison's library once the investors were paid back. The newspaper's investors would become shareholders and be reimbursed with 3 percent interest per month; once their investments were recouped, the library would own the paper and its profits would pay for new books and periodicals.

Shoonmaker and a handful of other inmates contributed to the cause, but the biggest investors ended up being the Younger brothers: Together, the three shelled out $50, one-fourth of the required start-up capital. Shoonmaker, who assumed the position of editor, also hired Cole, making him the associate editor and "printer's devil"—an old-fashioned term for a printer's assistant.

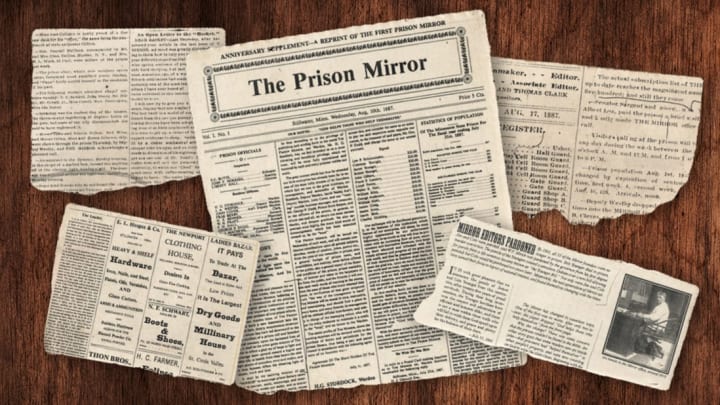

On August 10, 1887, The Prison Mirror was born. It cost 5 cents per issue, with yearly subscriptions going for $1, and issues were sold to prisoners and non-prisoners alike. Local merchants like wholesale grocers and various clothiers and tailors also purchased advertisements, which helped pad the editors' coffers.

Historians don't know how Shoonmaker became inspired to start the first prison newspaper west of the Mississippi, and the nation's only paper to be produced by inmates. But as James McGrath Morris, author of Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars, tells Mental Floss, the paper's founding fit with the idea of prison reform, a burgeoning national trend, while also pioneering a new form of penal journalism.

The first-known prison newspaper was technically founded in 1800, when a New York lawyer named William Keteltas fell upon hard financial times and was imprisoned in debtors' prison. The attorney made a case for his release by publishing Forlorn Hope, an advocacy newspaper that lambasted the criminalization of poverty and called for legal change. However, modern prison journalism's true roots can be traced back to the late 19th century, an era in which corrections officials "believed earnestly that prisons were intended to make better people of their inmates and release them into society," Morris tells Mental Floss.

Morris explains in Jailhouse Journalism that as imprisonment gradually replaced corporal and capital punishment, groups like the Quakers of Pennsylvania called for new jails that would shield inmates from corrupting influences, thus restoring their morality. These calls for change led to the first-ever American Prison Congress in 1870, in Cincinnati, Ohio. In attendance were officers and reformers from around the country, including a man named Joseph Chandler. He was a former congressman, and a member of the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons. More importantly, Chandler had once been a newspaper publisher.

Chandler noted that inmates clamored for newspapers, viewing them as a means of social communication and a window to the outside world. But these publications were filled with salacious details of crimes, which could lead a prisoner's recovering conscience astray. Chandler proposed the idea of a sanitized newspaper written specifically for those in prison. That way, inmates could stay abreast with the changing times, allowing them to re-enter society as informed men.

The American Prison Congress led to the formation of the National Prison Association, which would later become the American Correctional Association. Two years later, in 1872, a similar international convention was held in London. In the meantime, officials around the world began putting these new, enlightened ideals into practice, creating new types of prisons called "reformatories." One such institution was the Elmira Reformatory in New York, run by influential reformist Zebulon Reed Brockway.

Brockway had been at the 1870 American Prison Congress. Influenced by Chandler, Brockway hired an Oxford-educated inmate—whose name today is only remembered as Macauley—to run a newspaper called the Summary. First published in November 1883, the Summary was a news digest filled with carefully culled news items, coverage of prison happenings, and submissions from inmates and reformers. It was uplifting, laudatory, and above all, free from controversy. Across America, advocates clamored for more.

Soon, other reformatories began producing their own imitations of the Summary. These newspapers printed prisoners' edited articles, but officials—not inmates—technically ran the show. This would change in 1887 with The Prison Mirror.

The Prison Mirror's maiden issue was four pages long, 14 by 17 inches. It contained introductions, a reprint of the shareholders' business plan, and florid declarations of intent. Written collaboratively by the paper's founders, the opening article began:

"It is with no little pride and pleasure [that] we present to you, kind reader, this our initiative number of THE PRISON MIRROR, believing as we do, that the introduction of the printing press into the great penal institutions of our land, is the first important step taken toward solving the great problem of true prison reform."

The Mirror, they continued, would contain both humorous and literary submissions, and "a general budget of prison news, and possibilities, and realities, never before offered to the public." The authors promised to "encourage prison literary talent," "instruct, assist, encourage, and entertain," and "scatter words of warning to the outside world, whose reckless footsteps may be leading them hitherward."

Above all, the paper concluded, the Mirror would provide the prisoners with an independent voice, free from official interference: "This, we believe is the only printed sheet now in existence organized, published, edited, and sent forth to the world by prisoners confined within the walls of a penitentiary."

Also included in this first issue of the Mirror was a letter from the new warden, Halvur Stordock, who had been appointed by Governor Andrew R. McGill earlier that year. Stordock reassured outside readers that taxes didn't fund the Mirror and that the project had his full permission. "If it shall prove a failure, then the blame must all rest on me," he wrote. "If it shall be a success then all credit must be given to the boys who have done all the work."

It's unclear why, exactly, Stordock gave the prisoners such unprecedented free rein. Some critics later claimed that the warden used the Mirror as a publicity stunt; others said that he actually secretly edited the paper. The most likely explanation, however, is that unlike the reformers who founded the Summary, Stordock—a onetime farmer who had been appointed to his new position as a political favor after running for Minnesota Secretary of State—likely knew nothing about penology, or the complications or risks of running a prison.

The Mirror's first issues contained bits of prison news ("The stone steps leading into the new main cell building is a great improvement"), accounts of visitors, summaries of talks given at the prison, and letters from readers. Also included were vignettes from prison life. Some humorous ones featured printer's devil Cole Younger, whom the paper referred to as the staff's "Satanic member." In the inaugural issue, the Mirror published the below anecdote:

"A feat of activity occurred a few evenings since, in the prison cell room which is seldom ever equaled. The Satanic member of The Mirror force, carelessly laid upon the bench whereon he was sitting, a lighted cigar, officer A__n of the night force came up and with the dignity of a modern hero cooly seated himself upon the inoffensive little 'snipe'—a moment only, and the deed was done. Mr. A___ arose with the velocity of a Dakota cyclone, and it is needless to remark a sorer, if not a wiser man, but the fire was quenched. We do not wonder that the Warden is enabled to save the State seven or eight hundred dollars per year, on insurance, when he is provided with such an available fire extinguisher."

Soon after, however, both the paper's "Satanic member" and founding editor Shoonmaker would jump ship. In the Mirror's second issue, Shoonmaker resigned (presumably because he was due to be released on August 30) and handed over his responsibilities to a reluctant inmate named W.F. Mirick. ("I am afraid … that my fellow unfortunates, and the public outside have been led to expect at my hands more than they will receive," Mirick admitted in the paper's third edition, published on August 24, 1887.) Younger also resigned from the paper, perhaps because the job took his time and attention away from the prison library.

Stripped of its famous staffer, the paper now had to make its own name. This turned out to be a rather easy exercise, as its writers took on the unprecedented task of criticizing prison life, politicians, and even other newspapers.

Articles elicited compliments and condemnation from the outside world, and the Mirror printed them with relish. Newsmen debated among themselves whether inmates should be entrusted with the privilege of producing their own paper.

"The editor of the Taylors Falls Journal is having a controversy with THE PRISON MIRROR, a new paper printed inside the state penitentiary," the Rush City Post wrote in 1887. "We haven't seen THE MIRROR, but from the way the Journal squirms, we should judge it to be a lively paper."

And holding to the Mirror's promise to "speak the truth, whatever we conceive it to be," reform-minded journalists viewed the publication as a rare window into the depravities of prison life. In 1887, the Chicago Herald wrote:

"If the Minnesota project is to succeed, it must have a little life in it, and instead of praising the warden, guards, and keepers, it must show them in their hideous deformity. A journal published by jail-birds should be candid, sincere, bold, and even defiant … The reader should hear, or at least he should imagine that he hears, the clank of a ball and chain or the rude swoop of a manacled fist."

In the fall of 1887, The Prison Mirror became entangled in a highly political feud. The permissive Warden Stordock had replaced a warden named John A. Reed, who'd held the position for nearly 13 years. He was well respected but ousted on charges of allegedly mismanaging prison funds. When Stordock took over, "two of the three prison inspectors resigned because of Stordock's appointment, which they correctly thought was [Governor] McGill trying to make place for some of his political friends," according to a historical account provided by Brent Peterson, executive director of the Washington County Historical Society.

Several months after Warden Reed was dismissed, Stordock and new prison inspectors opened an investigation into his administrations. No one quite knows what sparked the scrutiny, but rumors swirled as the governor assembled an oversight committee.

"There were rumors about [Reed] using materials from the prison for his personal use," Peterson tells Mental Floss. "Then, there was even more of a bombshell: He was doing inappropriate things with female convicts and the matron. All of this was played out in the newspapers, and it turned out to be just wrong. False." (During this period in history, a handful of women were housed in the Stillwater Prison, in their own separate quarters.)

The rumors allegedly drove Reed to attempt suicide, according to Peterson. Meanwhile, the Mirror sided with their ally Stordock, and reprinted the accusations. This invoked the wrath of one of the state's most influential papers: The Minneapolis Tribune.

In a Sunday editorial published in October 1887, the Tribune went on the offensive: "A careful examination of the recent issues of the Prison Mirror … compels the frank opinion that it ought to be summarily suppressed or else reformed in all its departments," the Tribune wrote. They lambasted the Mirror for printing "the most offensive and adverse comments upon ex-Warden Reed's pending investigation," and for also commenting "freely and in shockingly bad taste upon inside prison matters."

"Men in the penitentiary are not as men at liberty," the Tribune concluded. "Among the other things denied them should certainly be the privilege of running a newspaper without restriction or responsible control."

Warden Stordock and other officials considered this advice. But before they could make moves to shut down the Mirror, another local paper—the St. Paul Daily Globe—chimed with an editorial titled "Don't Do It":

"It is said that Warden Stordock intends to suppress further publication of the Prison Mirror because a paragraph slipped into the columns of a recent issue alluding to the Reed-Stordock squabble … [the Mirror] has been the means of furnishing the convicts with a great deal of reading matter that they would not otherwise have had, and has in many ways been a source of light and comfort to lives, which, God knows, are cheerless enough at best. It is in the interest of humanity that the Globe appeals to the authorities of the Stillwater prison not to suppress the publication of this little paper."

Somehow, The Prison Mirror weathered the storm and stayed afloat. Later, the inmates admitted (but didn't apologize for the fact) that the Reed gossip had been inappropriate for their pages. After reaffirming their commitment to free speech, they resolved to forge on as normal. All this occurred within the first four or so months of the paper's existence—a time span that would ultimately prove to be the most vibrant in their history.

The Mirror continued printing monthly, but by 1890, it had lost the majority of its lifeblood: the original founders who first brought it to life. Just five members out of the original 15 remained in prison. Mirick, a convicted murderer, had been pardoned and released, and in 1901, Cole and Jim Younger were paroled after 25 years in prison. (Bob Younger had died in prison from tuberculosis.)

The Mirror also changed once Stordock retired and a new warden took over the position. Authorities now reviewed proofs of the paper, and over the years its tone, subject, and length shifted along with staff turnover and the current political climate. "Life is not static, it is dynamic," Martin Hawthorne, a vocational instructor at the prison who is also The Prison Mirror's supervisor, tells Mental Floss. "So too must be The Prison Mirror."

The Mirror—which recently celebrated its 130th anniversary—is still a vital cornerstone of prison life. In addition to the occasional hard-hitting investigation, each 16-page issue of the monthly publication offers a variety of features and recurring columns, like "Ask a Lawyer." Currently, 2225 copies are printed per month, with most going to inmates. Around 200 copies are regularly sent to prison advocacy groups, law schools, and other organizations and institutions.

"Since we publish events that touch or feature offenders that are incarcerated here," Hawthorne says, "they feel that it is their newspaper. It is almost like a small neighborhood paper. There is never an issue where someone doesn't know someone featured in the paper."

But unlike the 19th century Mirror, today’s product is heavily censored—both by authorities and the inmates themselves. To avoid retribution from sources or rebuke from authorities, contributors are forced to walk a delicate line between intrepid reporter and circumspect prisoner. They're unlikely to print anything that could place themselves in danger's way, or result in an issue being pulled. Then, the final product is reviewed by a host of critical eyes, including Hawthorne, the prison's education director, the associate wardens, the Office of Special Investigation, and finally, by the warden himself.

"In a correctional environment, we are always sensitive to any subversive illegal activities or gang references, so if any of these are noticed they are asked to remove them," Hawthorne explains. "We are also sensitive to victims’ rights. So if there is anything mentioned that may have an impact or reference on that, they are asked to remove it. Outside of those considerations, they are free to write about whatever they feel needs to be addressed at the time."

While limited by these constraints, the Mirror still manages to perform important journalism: In 2012, for example, an investigation conducted by paper editor Matt Gretz discovered that Minnesota lawmakers had taken $1.2 million in profits from the Stillwater prison canteen to balance out budget cuts in 2011. Typically, this money is used for inmate programs and recreational materials [PDF].

While not the freewheeling pioneer of free press it once was, the Mirror continues to serve as a vehicle for prisoners to let their voices be heard, just as it did in 1887. "Ours isn't a pretty history," reflected editor Gretz in 2012, in a commemorative issue celebrating the paper's 125th anniversary. "But we sure do have stories to tell."

This piece was updated on January 4, 2018 with new information from the Minnesota State Archives.