All spiders have eight legs, but that’s where most of their similarities end. Scientists frequently discover new species with unexpected talents—be it a flair for cartwheels or the ability to turn itself into a disco ball. Researchers have also found plenty of specimens that are just plain weird-looking. Here’s a list of 10 fascinatingly freaky arachnids.

1. CEBRENNUS RECHENBERGI // THE FLIC-FLAC SPIDER

A native of the Erg Chebbi desert in southeastern Morocco, Cebrennus rechenbergi—also known as the flic-flac spider—has the remarkable ability to cartwheel its way out of danger. When threatened by a predator, it will leap off the ground and do a series of high-energy somersaults to make a quick exit. An alarmed flic-flac spider can tumble forward at a rate of 6.6 feet per second—twice as fast as its maximum walking speed. If pressed, it can even cartwheel uphill. Such talents did not go unappreciated by this spider’s discoverer, bionics expert Ingo Rechenberg, who has built a somersaulting robot based on the flic-flac’s locomotion.

2. BAGHEERA KIPLINGI // A JUMPING SPIDER

Those who have read Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book may have already figured out that this species was named after the panther who helps raise Mowgli. But its pop culture connection is not Bagheera kiplingi’s only claim to fame. It has a plant-based diet, unlike nearly all other spiders, which subsist predominantly on meat. B. kiplingi feasts on the nutritious nubs of Central American acacias, which the trees produce to feed their colonies of guard ants. The ants protect the trees from predators, but the spiders have learned how to swoop in and steal the nubs without providing any symbiotic benefit. The spiders will also eat nectar and ant larvae, and when times are tough, they’ve been known to practice cannibalism.

3. ARACHNURA HIGGINSI // THE SCORPION-TAILED SPIDER

Two phobias for the price of one! Found only in Australia, the scorpion-tailed spider is so named because adult females have a long, thin appendage on the tip of their abdomens. (Males and juveniles lack this structure.) The females can arch this bendable tail over their backsides, which gives them the appearance of irate scorpions and prompts would-be attackers to keep their distance. But it’s all an act: The tail cannot sting and Arachnura higginsi is mostly harmless to humans.

4. CAEROSTRIS DARWINI // DARWIN’S BARK SPIDER

The male Darwin’s bark spider is eager to please. Really, really eager. The diminutive males exhibit what some scientists have called “a rich sexual repertoire” to their much larger mates. During sex, males nibble on their partners’ genitals or immobilize them with a web of silk before getting busy. Males will also detach their own sexual organs inside their mates to prevent females from mating with others. Researchers muse that this unusual behavior grew out of males’ survival instinct: A female Darwin’s bark spider is liable to eat her partner after mating.

5. GENUS SCYTODES // SPITTING SPIDERS

Using webs to catch prey is all well and good, but it almost seems tame compared to what spitting spiders do to their victims. To subdue a target, the killers take aim and fire twin streams of venom-drenched silk out of their fangs. At a top speed of 62 miles per hour, the fibers move in a wide-arced, zig-zag pattern. In addition to being coated with poison, this silk drips with a super-sticky glue. Once victims are enmeshed, the glue-covered fibers will shrink, constricting the unfortunate prey. Eventually, the spitting spider will administer a venomous bite and put the trapped entrée out of its misery.

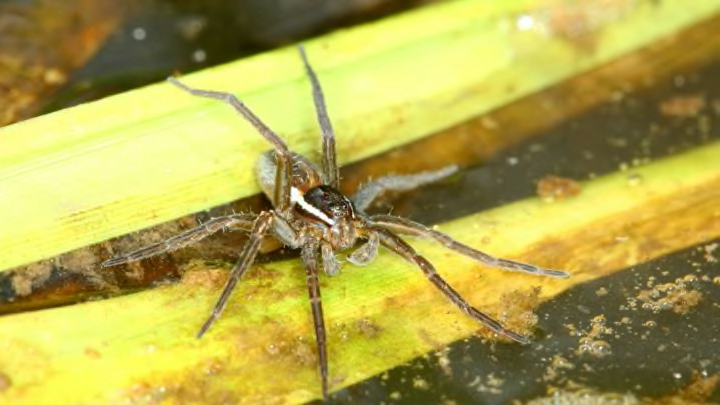

6. GENUS DOLOMEDES // FISHING SPIDERS

Hydrophobic coats and a knack for exploiting surface tension allow these predators to walk on water. Fishing spiders lurk in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. To hunt tadpoles, aquatic insects, and even small fish, many species of fishing spiders will splay themselves over the surface of freshwater lakes or streams. Then, using hundreds of ultra-sensitive leg hairs, they monitor aquatic vibrations. When prey swims by, the spider homes in on its precise location and dives for the victim, sometimes as much as 18 centimeters below the water’s surface.

7. CYRTARACHNE INAEQUALIS // A “DISCO SPIDER”

This little fellow—which arachnologist Joseph Koh believes is Cyrtarachne inaequalis, a member of the Cyrtarachne orb-weaver spider genus—made a vivid impression on photographer Nicky Bay, who captured its singular light show on film. The orb-weaver’s abdomen exhibits a pulsating movement that appear to show its internal organs working under a translucent membrane, Bay writes. Scientists have suggested that the spiders’ display attracts prey or scares off predators, but how and why C. inaequalis puts on its tiny disco act remains a mystery.

8. GENUS MYRMARACHNE // ANT-MIMICKING JUMPING SPIDERS

Found in tropical and temperate zones all over the world, Myrmarachne spiders pretend to be ants—which predators view as aggressive and not worth the effort—to stay alive. With their elongated heads and hourglass-shaped thoraxes, the arachnids look a lot like various ant species (their Latin name even means “ant-spider”). To help sell the illusion, they’ll wiggle their front legs like an ant’s writhing antennae. Of course, a good actor knows when to break character. If certain Myrmarachne species come across predators that eat ants, they’ll drop the ruse.

9. SUPERFAMILY PALPIMANOIDEA // ASSASSIN SPIDERS

Assassin spiders are so named because most of them eat smaller, sometimes poisonous spiders. To keep their food from biting back, Palpimanoidea have evolved long, skinny, giraffe-like necks. Their tiny heads sport huge sets of jaws. When an assassin spider finds a meal, those jaws impale the target and swing forward at a 90-degree angle. That keeps victims a safe distance away from any of the assassin spider’s sensitive body parts. Before long, the skewered prey will die on one of the distended jaws. Then the feasting can begin.

10. GENUS SELENOPS // SPIDERS THAT GLIDE

Our planet is home to more than 40,000 different kinds of spiders, and luckily for arachnophobes, none of them can fly. But at least one genus can free-fall like champion parachutists. In a 2015 study, biologists documented this unusual behavior by systematically dropping 59 tree-dwelling spiders of the genus Selenops from “either canopy platforms or tree crowns in Panama and Peru.” Ninety-three percent of these arachnids steered themselves towards nearby trees to land safely on the trunks. The researchers speculate that such gliding descents happen all the time in nature. After all, the spiders predominantly reside in trees—and the ability to parachute from one trunk to the next would be a huge asset.