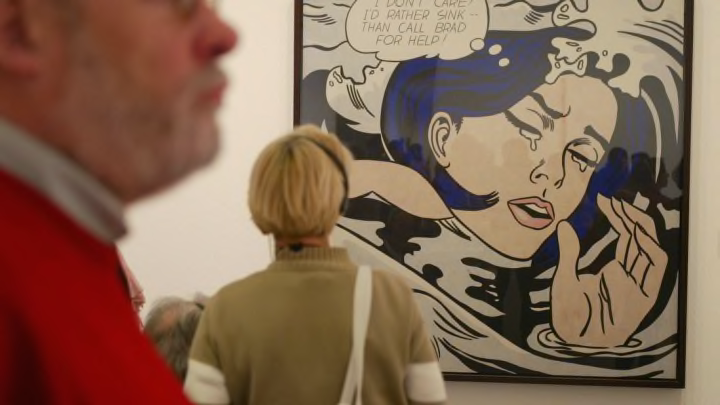

Arguably the most popular of American painter Roy Lichtenstein's works, Drowning Girl is an iconic landmark of pop art. But beneath its bold lines, clever circles, and rushing waves lies the story of a 40-something artist who finally found his calling by looking to kids stuff.

1. LICHTENSTEIN FOUND INSPIRATION IN COMIC BOOKS.

Though comic books had been overlooked by art critics, Lichtenstein, a Manhattan-born painter, relished in their bold lines, vibrant colors, and use of word bubbles to convey speech and thought. While the artist was also a sculptor and lithographer, he'd become best-known for his comic-influenced paintings, which elevated comics' low-brow aesthetic to high art.

2. HE EVEN MIMICKED THEIR PRINTING PROCESS'S LOOK.

At a glance, Drowning Girl might seem like she's printed like old-school comics. But Lichtenstein actually recreated this aesthetic with oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Brushing paint over stencils he'd perforated with a dot pattern, he mimicked the "tonal variations with patterns of colored circles that imitated the half-tone screens of Ben Day dots used in newspaper printing."

3. DROWNING GIRL IS A RIFF OFF A DC COMIC PANEL.

Lichtenstein lifted the imagery of the drowning girl and her thought bubble from the splash page of the 1962 comic Secret Hearts #83. There, a story called "Run for Love!" featured a full-page illustration with a drowning dark-haired girl in the foreground. In the background lies a small, capsized boat, and a befuddled blonde man holding on to it. For his 1963 homage, Lichtenstein cropped the image, bumped up the color, thickened the line work, and changed the thought bubble wording from "I don't care if I have a cramp! -- I'd rather sink -- than call Mal for help!" to "I don't care! I'd rather sink -- than call Brad for help!"

4. THE MAN'S NAME CHANGE WAS BECAUSE HIS DROWNING GIRL DESERVED BETTER.

"A very minor idea," Lichtenstein has said of the revision of Mal for Brad, "But it has to do with oversimplification and cliché." Or to simplify, he felt that his cartoon representation of frustrated American Womanhood demanded a boyfriend with "a heroic name." Mal just wouldn't cut it.

5. LICHTENSTEIN WAS A GROUNDBREAKER.

His peers Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns had already been bringing popular imagery into their work. But by dabbling in comic motifs as early as 1958, Lichtenstein was the first pop artist to dive into cartoons and comics, beating even Andy Warhol whose brush with comic-based pieces came in 1960.

6. BEFORE DROWNING GIRL, HE PAINTED MICKEY MOUSE AND POPEYE.

In her book Roy Lichtenstein, art historian Carolyn Lanchner pinpoints the summer of 1961 as when the painter moved away from Abstract Expressionism, which was popular at the time, and toward cartoon imagery, which was overlooked if not despised. The acclaimed artist recounted this stage in his evolution by saying, "The early (paintings) were of animated cartoons, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, and Popeye, but then I shifted into the style of cartoon books with a more serious content such as 'Armed Forces of War,' and 'Teen Romance.'" He continued, "I was very excited about and interested in the highly emotional content yet detached impersonal handling of love, hate, war, etc., in these cartoon images."

7. LICHTENSTEIN USED AN OPAQUE PROJECTOR TO COPY THE DETAILS OF THE COMICS.

This machine allows opaque objects—like a pencil sketch—to be projected onto a screen, or canvas. He once described the process thusly, "From a cartoon, photograph or whatever, I draw a small picture—the size that will fit into my opaque projector ... I don't draw a picture in order to reproduce it—I do it in order to recompose it ... I project the drawing onto the canvas and pencil it in and then I play around with the drawing until it satisfies me." This process allowed Lichtenstein to work out composition and minor details on large canvases, like Drowning Girl which measures in at 67 5⁄8 inches by 66 3⁄4 inches.

8. THESE LICHTENSTEIN PIECES ARE REGARDED AS PARODIES.

He also crafted works inspired by Cézanne, Mondrian, and Picasso, which were likewise dubbed "parodies" by art critics. But Lichtenstein rejected this description—he didn’t want viewers to think he was mocking the works of others. Instead, he insisted, "The things that I have apparently parodied I actually admire."

9. DROWNING GIRL HAS HIGHBROW INSPIRATIONS AS WELL.

The pastiche-loving pop artist confessed that his use of blacks and blues to create the waves and the curls of the girl's hair was influenced by Japanese printmaker Hokusai's world-famous wood-block print The Great Wave off Kanagawa. "In the Drowning Girl the water is not only Art Nouveau," Lichtenstein explained, "But it can also be seen as Hokusai. I don't do it just because it is another reference. Cartooning itself sometimes resembles other periods in art—perhaps unknowingly ... They do things like the little Hokusai waves in the Drowning Girl. But the original wasn't very clear in this regard—why should it be? I saw it and then pushed it a little further until it was a reference that most people will get ... it is a way of crystallizing the style by exaggeration."

10. BRAD WAS A RECURRING CHARACTER.

While that cad Brad doesn't make into the frame of Drowning Girl, the mentioned boyfriend can be found in Lichtenstein's 1962 painting Masterpiece. There, a blonde woman says through speech bubble, "Why, Brad darling, this painting is a masterpiece! My, soon you'll have all of New York clamoring for your work!" But between the scenes something bitter must have befallen this mysterious beau. In 1963's I Know How You Must Feel, Brad ...”, he's out of frame, leaving a brooding blonde girl thinking, "I know how you must feel, Brad…"

11. CROPPING AND TWEAKING COMIC PANELS MAKES THEM UNIQUELY LICHTENSTEIN'S.

The provocative painter became known for focusing in on expressions of comic panels, and revamping their thought bubbles to play to a new context. In a recent re-assessment of Drowning Girl, Expressionist artist Vian Shamounki Borchert felt Lichtenstein's cropping suggests a woman drowning in her own tears over that dreadful Brad. Meanwhile, art critic Kelly Rand saw the hurt heroine as being "in a suspended state of distress," pointing out that the lack of any context leads the viewer to ask what’s happening. Had the boat and the heroine's lamentable beau been left in the frame, the meaning of the image would have shifted to a far more literal sense of peril.

12. APPROPRIATION FROM COMICS MADE DROWNING GIRL.

Drowning Girl had a coveted spot in some of Lichtenstein's early '60s art shows, and over the years has become one of his most adored creations. But even as his comic-inspired pieces made him famous in his 40s, a debate raged over whether this comic appropriation or parody was art at all. In 1963, New York Times critic Brian O'Doherty infamously declared Lichtenstein "one of the worst artists in America," bristling that the painter won praise as he "briskly went about making a sow's ear out of a sow's ear." Then in 1964, Life magazine covered the brewing art scene kerfuffle with the hurtful headline “Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?”

13. THE TIDE TURNED FOR DROWNING GIRL.

Critics may have initially huffed, but over the decades, no one could deny that Lichtenstein's comic-influenced works had a lasting allure. Art collectors paid out enormous amounts to claim them as their own. Drowning Girl was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in 1971, and has been a proud part of their permanent collection ever since. Lichtenstein won redemption in 1986, when Life re-evaluated his works, declaring him "always the most thoughtful of the pop artists ... [who] had the most to say. Those cartoon blowups may have disturbed the critics, but collectors, tired of the solemnity of abstract expressionism, were ready for some comic relief. Why couldn't the funny pages be fine art?'' Ultimately, this daring artist's re-interpretation challenged art critics and broader audiences to examine their own biases. As his work grew in popularity, so did the art community's respect for comics and cartoons. Lichtenstein—who lived until 1997 and the ripe age of 73—had the chance to see the sea change he'd begun in the world's understanding of art.

14. WOMEN IN PERIL BECAME A THEME FOR THE PAINTER.

Now heralded as a "masterpiece of melodrama," Drowning Girl is by far the most famous of these. Other titles from this unofficial series include Crying Girl (1963), Crying Girl (1964), Hopeless, In the Car, and Oh, Jeff...I Love You, Too...But.... Each painting hints at a story, which the viewer is urged to imagine. It's believed this invitation to collaboration is a major part of what has made Lichtenstein's comic art, and particularly Drowning Girl, remain a popular attraction to museum visitors, even decades later.

15. LICHTENSTEIN BECAME CELEBRATED AS NOT JUST A PAINTER, BUT A STORYTELLER.

In 2012, Washington's National Gallery of Art helped put together a rousing Lichtenstein retrospective which did not shy away from his comic-inspired art, but rather relished in it. More specifically, a conversation emerged about the carefully selected images Lichtenstein plucked from comics. National Gallery curator Harry Cooper told NPR the artist "really looked hard for these comics that had a kind of crux of the story in them," then applied his unique perspective to them to open them up to an audience who might never touch a comic book, but could nonetheless be enchanted with their stories. With that, he helped elevate pop art to a place where it could not be ignored or written off as a "just a gimmick, just a joke." Though Lichtenstein experimented in many forms of art and style over his long career, it was his embracing of comics in works like Drowning Girl that secured his legacy as a painter, a pop art pioneer, and a visual storyteller in his own right.