Hurricanes are among the largest and most intense storms nature can produce. Today, we know more about these systems and have an easier time measuring and predicting them than ever before. But there’s more than meets the eye when it comes to hurricanes. As hurricane season kicks off (it runs from June 1 through November 30 each year), here are some things you might not know about these dangerous storms.

- Hurricanes are only “hurricanes” around North America.

- Hurricanes come in all shapes and sizes.

- The greatest danger in a hurricane is in the eyewall.

- The eye of a hurricane is very warm.

- You can tell a lot about a hurricane by its eye.

- Some hurricanes have two eyes.

- The strong winds that a hurricane creates are only part of the danger.

- California rarely sees tropical cyclones.

- Hurricane hunters fly planes into storms.

- Hurricane hunters drop sensors to measure waves.

- We started naming hurricanes to keep track of them.

- Hurricane names are retired if the storm was especially destructive.

Hurricanes are only “hurricanes” around North America.

A tropical cyclone is a compact, low-pressure system fueled by thunderstorms that draws energy from the heat generated by warm ocean waters. These tropical cyclones acquire different names depending on how strong they are and where in the world they form. A mature tropical cyclone is called a hurricane in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific oceans. The same storm is called a “typhoon” near Asia and simply a “cyclone” everywhere else in the world.

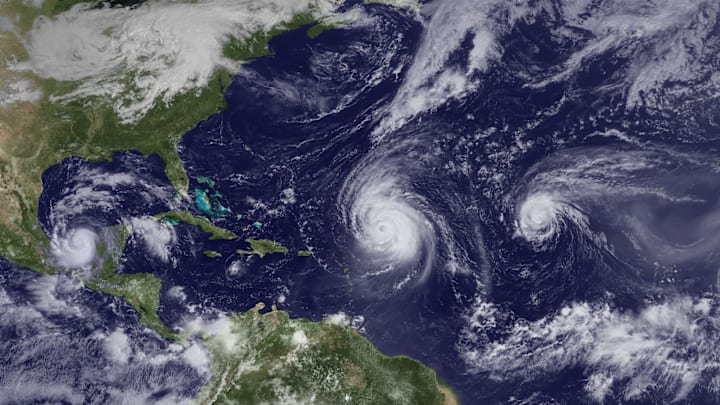

Hurricanes come in all shapes and sizes.

Not all hurricanes are picture-perfect. Some storms can look so disorganized that it takes an expert eye and advanced technology to spot them. A full-fledged hurricane can be as small as a few dozen miles across or as large as one-half of the United States, as was the case with Typhoon Tip in the western Pacific Ocean in 1979. The smallest tropical cyclone on record was 2008’s Tropical Storm Marco, a tiny storm in the Gulf of Mexico that almost made it to hurricane strength. Marco’s strong winds only extended 12 miles from the eye of the storm—a distance smaller than the length of Manhattan.

The greatest danger in a hurricane is in the eyewall.

The spiraling bands of wind and rain that radiate from the center of a hurricane are what give these storms their distinctive buzzsaw shape. These bands can cause damage, flooding, and even tornadoes, but the worst part of a hurricane is the eyewall, or the tight group of thunderstorms that rage around the center of the storm. The most severe winds in a hurricane usually occupy a small part of the eyewall just to the right of the storm’s forward motion, an area known as the right-front quadrant. The worst damage is usually found where this part of the storm comes ashore.

The eye of a hurricane is very warm.

The core of a hurricane is very warm—they are tropical, after all. The eye of a hurricane is formed by air rushing down from the upper levels of the atmosphere to fill the void left by the low air pressure at the surface. Air dries out and warms up as it rapidly descends through the eye toward the surface. This allows temperatures in the eye of a strong hurricane to exceed 80°F thousands of feet above the Earth's surface, where it’s typically much colder.

You can tell a lot about a hurricane by its eye.

Like humans, you can tell a lot about a hurricane by looking it in the eye. A ragged, asymmetrical eye means that the storm is struggling to strengthen. A smooth, round eye means that the storm is both stable and quite strong. A tiny eye—sometimes called a pinhole or pinpoint eye—is usually indicative of a very intense storm.

Some hurricanes have two eyes.

An eye doesn’t last forever. Storms frequently encounter an “eyewall replacement cycle,” which is where a storm develops a new eyewall to replace the old one. A storm weakens during one of these cycles, but it can quickly grow even more intense than it originally was once the replacement cycle is completed. When Hurricane Matthew scraped the Florida coast in October 2016, the storm’s impacts were slightly less severe because the storm underwent an eyewall replacement cycle just as it made its closest approach to land.

The strong winds that a hurricane creates are only part of the danger.

While strong winds get the most coverage on the news, wind isn’t always the most dangerous part of the storm. More than half of all deaths that result from a landfalling hurricane are due to the storm surge, or the sea water that gets pushed inland by a storm’s winds. Most storm surges are relatively small and only impact the immediate coast, but in a larger storm like Katrina or Sandy, the wind can push deep water so far inland that it completely submerges homes many miles from the coast.

California rarely sees tropical cyclones.

It can seem odd that California occupies hundreds of miles of coastline but always seems to evade the hurricane threat faced by the East Coast. California almost never sees tropical cyclones because the ocean is simply too cold to sustain a storm. Only a handful of tropical cyclones have ever reached California in recorded history—the worst hit San Diego in 1858. The San Diego Hurricane was an oddity that’s estimated to have reached category 1 intensity as it brushed the southern half of the Golden State.

Hurricane hunters fly planes into storms.

Aside from satellite and radar imagery, it’s pretty hard to know exactly what a hurricane is doing unless it passes directly over a buoy or a ship. This is where the Hurricane Hunters come in, a brave group of scientists with the United States Air Force and NOAA that flies specially outfitted airplanes directly into the worst of a storm to measure its winds and report back their findings. This practice began during World War II and has become a mainstay of hurricane forecasting in the decades since.

Hurricane hunters drop sensors to measure waves.

The Hurricane Hunters assess the storm with all sorts of tools that measure temperature, pressure, wind, and moisture, and have weather radar onboard to give them a detailed view of the entire storm. They regularly release dropsondes to "read" the inside of the storm. Dropsondes are like weather balloons in reverse: instead of launching weather sensors from the ground into the sky, they drop them down through the sky to the ground. The Hurricane Hunters also have innovative sensors that measure waves and sea foam and use the data to accurately estimate how strong the winds are at the surface.

We started naming hurricanes to keep track of them.

Meteorologists in the United States officially started naming tropical storms and hurricanes in the 1950s to make it easier to keep track in forecasts and news reports. Since then, naming tropical cyclones has become a worldwide effort coordinated by the World Meteorological Organization, the United Nations agency responsible for maintaining meteorological standards. Today, the Atlantic Ocean and eastern Pacific Ocean each receive a list of alternating masculine and feminine names that are reused every six years.

Hurricane names are retired if the storm was especially destructive.

If a storm is particularly destructive or deadly, the WMO will “retire” the name from official lists so it’s never used again out of respect for the families of the storm’s victims and survivors. When a name is retired, another name starting with the same letter takes its place. More than 80 names have been retired from the Atlantic Ocean’s list of names since 1954. For example, the names Florence and Michael have been retired as a result of the damage they caused during the 2018 hurricane season; they have been replaced with Francine and Milton in the 2024 list.

Read More Stories About Weather:

This piece originally ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2024.