The Pennsylvania Gazette published the morning of April 21, 1790, was rimmed in black. Flags across the city, and on the ships in the harbor, fluttered at half mast, and some 20,000 people crowded the streets.

“On Saturday night last departed this life ... Dr. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, of this City,” the paper read. “His Remains will be interred THIS AFTERNOON, at four o'clock, on Christ-Church burial ground.”

It was the largest funeral the city had ever seen; nearly half of Philadelphia’s population had come out to view the beloved Founding Father’s funeral procession.

It began at the State House (now called Independence Hall), where Franklin had served as Pennsylvania’s delegate to the Constitutional Convention three years earlier, just as his health was beginning to weaken. Clergy of all faiths came first, followed by Franklin’s casket, which was carried by some of Pennsylvania’s most important men—the president of Pennsylvania, the former mayor of the city, and the president of the Bank of North America among them. Next was Franklin’s family, and finally, there were printers, members of the fire company and the Philosophical Society, judges and state assemblymen, and politicians.

Church bells were muffled and tolled as the procession wound its way from the State House to Christ Church Burial Ground at the intersection of 5th and Arch Streets. As Franklin was lowered into the ground, the militia fired their guns. The grave was filled with dirt. Some time later, a blue marble ledger tablet, weighing over 1000 pounds, was laid on top.

It was exactly what Franklin had wanted. Though he had written an elaborate mock epitaph as a 22-year-old (which began, “The Body of B. Franklin, Printer; Like the Cover of an Old Book, Its Contents Torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms”), he outlined something much simpler when he updated his will in 1788. Franklin wrote that he wanted to be buried next to his wife, Deborah, in the family plot. He asked that “a marble stone,” made by mason David Chambers, “6 feet long, 4 feet wide, plain, with only a small moulding round the upper edge,” reading “Benjamin And Deborah Franklin 178-” be “placed over us both.”

For the next 70 years, the Franklin family plot was hidden from view by the brick wall that enclosed Christ Church Burial Ground (which, at that time, was closed to the public). Then, in the 1850s, an article lamenting the condition of Franklin’s gravesite, and its lack of access, ran in newspapers across the country. “A dilapidated dark slab of stone … marks ... the spot where rest the remains of Benjamin and Deborah Franklin,” it read. “So well hidden is THIS grave, and so little frequented, that we have known many native Philadelphians … who could not direct one to the locality where it may be found.”

In response to pleas from the public, Christ Church eventually replaced a section of the wall next to the grave with a wrought-iron fence in 1858. This may have been when the Franklins’ marble marker—which some felt was too simple a memorial for such a great American—was placed in an elevated granite platform to give the site more of a monument feel.

Making Franklin’s grave visible from the sidewalk was great for the public, but not so great for the condition of the Founding Father’s ledger tablet. As decades passed, thousands of visitors stopped by, and when his name became attached to an idiom he never actually said—“a penny saved is a penny earned”—people began tossing pennies on the grave. In the 1950s, the Church made repairs to the tablet and covered the grass surrounding the graves with red bricks. All the while, the public continued to toss coins and mementos onto the grave, creating pockmarks and pitting in the tablet’s surface, while moisture gathered beneath it in the granite base.

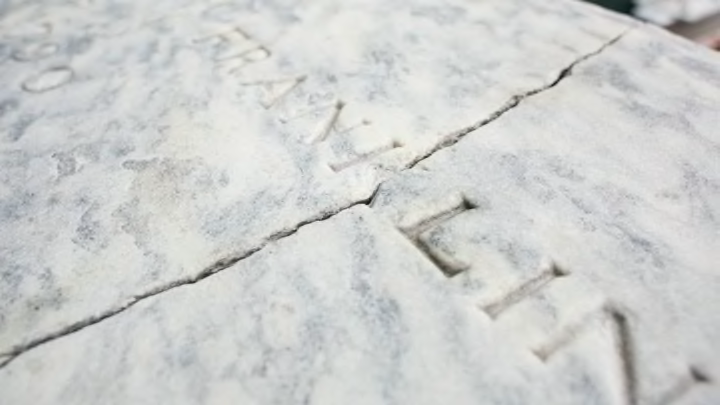

And then, one day—no one is quite sure when—a crack appeared, running right through the K in Franklin.

The staff at Christ Church Burial Ground monitored the crack for decades until, in 2016, they knew they had no choice but to act. Growth of the fissure was still accelerating, putting one of the most important gravesites in the United States at risk of being lost forever. Keeping the crack from getting worse would require the expert work of conservationists, funds from the public—and a little help from a rock star.

There are more than 4000 people interred at Christ Church’s 2-acre burial ground, which is located in Philly’s Old City neighborhood not far from Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell. There are five signers of the Declaration of Independence and two signers of the Constitution interred there, but Franklin is by far its most popular resident: Hundreds of thousands of people file by the fence next to his grave each year, and 60,000 pay an entry fee to come into the burial ground itself to pay their respects.

Also watching over Franklin is John Hopkins, who has served as caretaker of the Christ Church Burial Ground for 15 years. In addition to maintaining the stones and deciding which will be fixed, Hopkins manages a staff of tour guides, runs the tourism program, deals with upkeep of the grounds, and handles interactions with descendants of the people interred there. By his estimation, he’s spent more time with Franklin than the people who knew the Founding Father when he was alive. He’s a bit of a Franklin obsessive, able to drop idioms and facts at random. There’s an incredibly detailed Franklin action figure, which holds a hawk feather, on his desk. (It’s joined by photos of Edgar Allan Poe, a banner bearing the names of burial ground residents, and a red fedora adorned with the Phillies logo.)

Hopkins has had his eye on the crack from the moment he became caretaker. “Every year, I’d get a ruler and measure it,” he says. For most of his tenure, growth of the crack was slight but steady, “enough to cause concern.” The Franklin marker had long been on his list of stones to fix, but because it wasn’t a safety issue—“repairing any stones that may fall and hurt a visitor” is the number one priority, he says—Hopkins had to put it off.

Materials Conservation, a Philadelphia-based company that specializes in restoring architecture, art, and gravestones, works its magic on about 20 Christ Church markers chosen by Hopkins each year. Marco Federico, senior conservator at the company, became concerned about the fissure in Franklin’s tablet around five years ago. Based on what he and his team knew about historic materials, he says, they explained to the Christ Church Preservation Trust that the combination of marble ledger tablet and granite base was a very bad one. “Marble is calcium carbonite, a metamorphic [rock], and it needs to breathe. When it’s wet, it needs to dry out,” Federico says. “Granite, which is an igneous rock, does not readily allow moisture to pass through it.”

Marble, he explains, expands when it’s wet and contracts when it’s dry. When the stone can fully dry out, it’s not a problem—but when the top of the marble dries and the bottom half is still wet, it causes the stone to warp. “If only half the stone is drying out while the bottom continually remains saturated,” Federico says, “fatigue failure will eventually occur and it will shear in half.”

Which is precisely what happened with Franklin’s marker: Much like a bathtub, the granite base the tablet sat in was holding water, and with no way to drain, that water sat until it dried up on its own—which could take weeks or months. The water kept the marble from drying out completely until the stone was so warped and stressed that it cracked. With repeated wet/dry cycles, Federico says, “we knew that crack would start to get bigger and bigger.”

And get bigger it did. In the past couple of years, growth of the crack accelerated—and it became clear to Hopkins and Federico that the time had come to deal with it, or risk the damage becoming too great to save the stone.

The Christ Church Preservation Fund secured $70,000 worth of grants to repair the tablet, but it wasn’t enough to cover the full costs; they’d need an additional $10,000 to get the job done. That’s a lot of pennies, but Hopkins had an idea about how to get the funds.

In the early 1750s, Franklin managed a lottery to fund the construction of the building’s steeple, selling tickets to Philadelphia’s citizens until the church had enough money. “Some of us jokingly believe he probably had some ulterior motives, to do some experimenting with the electricity and the height of the building,” Hopkins says. “There were a lot of people involved in the lottery, but Franklin was the big loud guy that could talk you into buying the tickets.”

Franklin, Hopkins reasoned, had been the ultimate community guy, one who was "kickstarting" long before Kickstarter—so why not follow his example and start a GoFundMe to raise money for the restoration of his grave?

The campaign went live in November 2016, and the public stepped up right away, leaving messages along with their donations. “The embodiment of freedom and enlightenment. Thank you Ben Franklin for inspiring the ages!” wrote one supporter. “A true Philadelphia landmark that should be preserved!” wrote another. (Our personal favorite: “Fart proudly, neighbor!” Franklin loved a good fart joke.) Even the Philadelphia Eagles got in on the action, donating $1000—which delighted Hopkins, an enthusiastic Philly sports fan.

But the single biggest donation came from a seemingly unlikely source: New Jersey-born musician Jon Bon Jovi and his wife Dorothea. “I didn’t realize he was a big history buff,” Hopkins says. “He gives a lot of money to different organizations in Philadelphia. The fact that he was interested in our project was really cool and brought more attention to it.”

The GoFundMe reached its goal in just a day, eventually raising more than $14,000. The restoration was a go—which meant that Federico and his team had to get to work.

Before they could get started, the Materials Conservation and Christ Church teams had to come up with a plan of attack. They decided that, after lifting the marker, they’d sand down the edge of the granite base and add weep holes for water to drain; raised granite plinths would be placed on the base, and the tablet set back on those—leaving a small gap between the underside of the marker and the granite base. Water would drip off the tablet or drain through the weep holes, allowing the marker to fully dry out.

“We want to do as little as possible, basically,” Federico says. “We don’t want to do 100 percent restoration and have a brand-new-looking stone—we want to conserve the object as it is, and allow this historic resource to have a vastly increased lifespan.” Without the restoration, Federico estimates that the tablet would have cracked completely in three to five years. The restoration could allow the stone to remain on view for another 100 years.

Federico wasn’t sure how bad the crack was—there was no way of knowing until they had lifted the tablet—but he knew there was a chance the tablet would break as they were removing it from the base. He believed he could get under the stone via two broken corners, which provided the most access, and bridge the crack with a piece of stainless steel, then block the tablet up on wood a little bit at a time: a sixteenth of an inch at a time and then a quarter-inch at a time.

That’s exactly what Federico’s team tried—until the stone, still saturated, began to bend at the crack.

The team changed their approach. They fabricated stainless steel s-hooks and used compressed air to blow out debris (mud and “dirty little pennies”) from the area under the stone. They slid the tiny steel levers between the gap of the ledger tablet and the granite base. And then, they began to lift.

Federico kept his eye on the crack as two assistants used levers and a fulcrum to lift from the side. They proceeded carefully, lifting in small increments. Finally, after a tense hour, they had hoisted the ledger tablet high enough to slip a 2-by-4 piece of wood under each end, which allowed them to lift while spreading the load over the crack. “Once we were able to do that, it just became standard procedure,” Federico says. They lifted again, added a piece of wood, lifted again, added a piece of wood, until the tablet was raised around 8 inches off the granite base, supported on either end by a stack of wood.

But they still weren’t finished. The next step was to bolt two longer pieces of wood to the lateral pieces on either end, creating a frame—which is what they’d lift when they moved the tablet for real. With that task finished, they took off for the weekend, leaving the tablet sitting on foam-wrapped wood. The final piece of heavy lifting would happen on Monday.

Federico has conserved many gravestones during his 10 years as a conservator, but none are quite like this one. “If you’re looking for, like, the most iconic figure in American history, it’s hard to top Franklin,” he says. “There is only one Ben Franklin, and there’s only one Ben Franklin marker, and the way that Philadelphians and tourists interact with that marker—there's a very public connection. I wouldn’t say there was extra pressure, because we’re used to working on objects and materials of tremendous historical and cultural significance. But it’s not like the run of the mill thing, either.”

Finally, the day came to really lift the tablet: April 17, the anniversary of Franklin’s death. A green tarp had been secured over the wrought iron fence that faced the street, but Federico and his team still had an audience—the Bon Jovis. “I hate having an audience when I think that there's a chance for catastrophic failure, because no matter how many precautions you take, things break,” he says. “Catastrophic failure can happen at any time for any number of reasons.”

Redundancy is your friend when you’re dealing with a very heavy priceless object, so all of the equipment used to lift Franklin’s marker was built to handle as much of a load as possible. “Usually when you’re lifting a load, you want to be sure that all your straps, chains, and clevises, are rated for twice the load you’re lifting,” Federico says. “It’s better to be at triple knowing you have an audience and your mistakes could easily turn you into an eternal meme for failure!”

The goal was to lift the frame holding Franklin’s marker off the wood blocking and place both frame and tablet safely on a nearby metal frame table. Using a chain hoist on an I-beam, they slowly lifted the tablet and swung the stone 3 feet to the side. Federico was “hyper-aware, with every sense of my being focused on the slightest movement.” Then they carefully lifted it 3 feet off the ground.

Success. They wheeled the table underneath the marker and safely set it down. The whole process took about six hours. “When Benjamin Franklin’s grave marker is dangling by a chain and you acknowledge that chain’s performance will define your life’s work, yeah, it feels good to know it’s safe and sound on a table,” Federico says.

Plus, it was pretty cool to have Bon Jovi there. Not only did it give Federico’s team an excuse to really take their time, but “Mr. Bon Jovi was really as low-profile about it as he could have been,” Federico says. “He was very interested in how the tablet was made, and what the conditions were, and how we were going to repair it and what it would look like when it was repaired. His interest is really sincere and genuine, and so we appreciated that.”

It’s a gray day in late April, and the tarp is still up over the fence at Christ Church Burial Ground. The barrier gives the Materials Conservation team privacy to get their work done. “The most common question we get when we’re working in the graveyard,” Federico says, “is ‘Are you digging them up?’” (For the record, the answer is always no.) A worker uses a wet saw with a diamond blade on a track to precisely cut down the edges of the granite base, one-sixteenth of an inch at a time; at one end of the base—where the top of Franklin’s tablet used to sit—is wet granite dust and three-quarters of an inch of milky water from yesterday’s rain.

A few feet away, under a tent, Franklin’s tablet sits on a 4-by-4 wood frame. Federico has spread sample pucks full of composite repair mortars in various shades of gray on top, which he’ll eventually use to fill in the crack. “We’re going to match the composite mortar to the lighter color of the tablet,” he says, “and then we’ll use a mineral stain to go over the lighter area to continue these dark striations.”

The conservator has his work cut out for him. When they lifted the tablet out of its granite base, the team realized that the slab was cracked all the way through up until the bottom third of the stone. In addition to stabilizing the crack, Federico will also need to repair the two corners that had broken off, and treat the stone with a consolidant. “We look at stone as a monolithic thing, but it’s actually sort of like grains within a matrix,” he says. “The stone consolidant works its way into the matrix and strengthens these intergranular bonds.”

Federico began the restoration by treating the underside of the tablet with composite repair mortar, a cementitious material that he applied using a brush while lying on his back under the tablet, “like painting the Sistine Chapel.” Then he carefully drilled into the tablet on either side of the crack—“on the underside,” he jokes, because “it’s Franklin, not Frankenstein”—to make holes for seven stainless steel sutures that will sit flush with the tablet and bridge the crack to keep it from getting wider.

Next, he’ll need to clean the fissure. “You can see all the dirt in there—this has been open for a long time,” he says. “Not just water, not just dirt—little things crawl in there and make their homes. I don’t know who’s going to fall out of there when we open that up.” He also needs to remove and reset a big chunk of marble that’s currently sitting loose in the crack.

Then, using a syringe, he’ll fill the voids beneath the surface of the stone with a lime-based injection grout. The bottom “is so small that I can’t fill it,” Federico says, “but the top part of the crack will get filled. The underside has already been prepared, so whatever we inject will just flow down to that side and sit in there.” Finally, he’ll apply composite repair mortar on top of the grout with a micro spatulum and use the mineral stain to make it match. “The crack will still read as a crack, if you know where to look,” Federico says, “but it’s going to be greatly reduced in visibility.”

The crack runs directly through the K in Franklin, and Federico will fix that letter, too—but he’ll have Franklin’s final wishes in his mind as he does it. “I want to mess with this inscription as little as possible,” he says, “because as far as we know, this has not been recarved, this has not been touched up. The spacing of the lettering, all those marks are from when they were cut back in 1790.” After he’s filled the crack there slightly, he’ll go back during aesthetic integration and use mineral stain to do what he calls in-painting. “Once we treat it with mineral stain,” he says, “it’ll look and shade just the way the K initially had.”

But even once the crack is stabilized, and the tablet is back in place, it won’t be out of danger entirely. “The pennies!” Federico says. “God help us, the pennies.”

Those who pay their respects to Franklin by throwing pennies on his grave are doing it in honor of a phrase he didn’t even coin. (Sorry not sorry for those puns.) Variations on “a penny saved is a penny earned” date back to the 1600s; Thomas Fuller, for example, wrote “a penny saved is a penny gained” in 1662. Franklin put his spin on it, “a penny saved is a penny got,” in his 1758 issue of Poor Richard’s Almanack, and by the late 1830s, was erroneously credited as the originator of the quote “a penny saved is a penny earned.” (Nevermind that, as Blaine McCormick and Burton Folsom point out at Forbes, Franklin—an experienced businessman—“knew that a penny unspent in the competitive marketplace could never be equivalent to a penny earned in revenue.”) Two decades later, Christ Church opened up the wall beside Franklin’s grave, and, at some point, the penny throwing tradition began—and now, that tradition is having disastrous consequences for the tablet.

Marble, though it’s stone, is actually pretty soft. “That’s why [artists] carve things out of it,” Federico says. Get him started on the pennies, and he quickly becomes heated. “If you were to walk into the Philadelphia Museum of Art and just start throwing pennies at things, it would be completely unacceptable,” he says. “For us, it would also be completely unacceptable to be throwing any object at a historic monument like a grave marker.”

It might be hard to tell from afar, but up close, it’s easy to see, and to feel: The surface of Franklin’s tablet, especially the side closest to the street, is pockmarked and pitted from years of impacts—not just from pennies, but from nickels and quarters, souvenirs and mementos. “We can’t really protect the stone at night,” Hopkins says. “People use sticks to try to steal the pennies off the tablet.”

The tablet didn’t crack because of the pennies, but they do damage nonetheless. A close inspection of the stone reveals bright white flecks, evidence that the surface is degrading. Sadly, there’s nothing that can be done about that damage. “There's no good way to treat all of the pitting on the stone,” Federico says. “You just hope it weathers well and that it doesn’t continue to happen with such intensity that you cause areas where the water pools up on the stone, because as people continue to throw pennies on this, eventually that’s what's going to happen.”

Hopkins says that he removes between $3000 and $4000 worth of pennies from Franklin’s grave annually, funds that go right back into the preservation of the graves in the burial ground. But the benefits of the tradition don’t outweigh the cost. “As the caretaker of this burial ground, I take it very personally,” he says. “None of these other stones we even let people touch, let alone throw something on.” Tour guides who aren't affiliated with the Church stand by the fence and encourage people to throw pennies. “This is one of the greatest Americans of all time, and that’s all you can say about him?” Hopkins says. “And you don’t even mention his wife? I take it personally.”

So Hopkins is trying to educate the public in the hopes that they’ll quit throwing pennies. And if they don’t, the situation will one day reach a point of no return: “Once water starts pooling on top of it, with that crack, it’s really going to shorten the lifespan of the marker,” Federico says. “That’s when we may have to say, ‘Time to take it out of public view.’ And nobody wants that to happen.”

When he died at the age of 84 in 1790, Philadelphia’s Federal Gazette called Franklin a “FRIEND OF MANKIND” who possessed “singular abilities and virtues,” writing, “it is impossible for a newspaper to increase his fame, or to convey his name to a part of the civilized globe where it is not already known and admired.”

That was not exaggeration: Across the ocean, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Count of Mirabeau proclaimed to the French National Assembly that Franklin was “a mighty genius” who “was able to restrain alike thunderbolts and tyrants.” The Frenchmen wore black armbands; at home, members of the House of Representatives wore mourning colors for a month.

From the devices he invented to the republic he helped create, it’s impossible to quantify all that Franklin has given us. With this conservation, the team at Christ Church and Materials Conservation have done their part to keep the Founding Father’s legacy alive, and his ledger tablet around for generations to come. “I can rest easily in the grounds knowing that [his tablet] is going to be preserved beyond my years,” Hopkins says.

But how the tablet fares after this is up to the public. So the next time you're walking down Arch Street and pass Franklin's grave, stop to honor the man, admire the hard work that went into preserving his final resting place—and keep those pennies in your pocket.