If you were a grand gentlemen of the Georgian era, having a huge country house with lavishly landscaped grounds wasn’t enough to impress your visitors. No, you needed a little something extra. You needed an ornamental hermit.

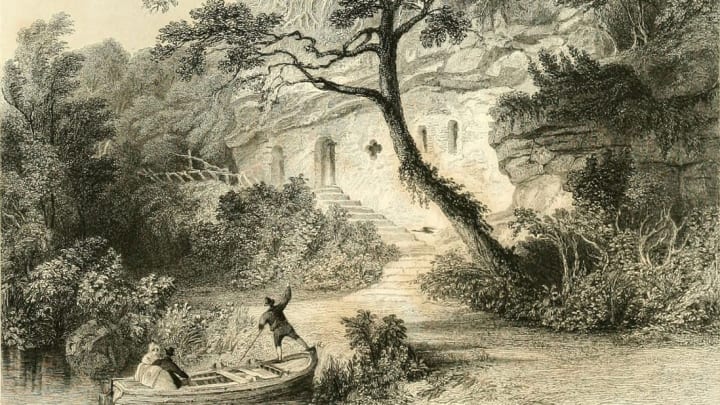

True hermits, those who shun society and live in isolation to pursue higher spiritual enlightenment, had been a part of the religious landscape of Britain for centuries. The trend of adding hermits to estate grounds for aesthetic purposes arose in the 18th century out of a naturalistic influence in British gardens. Famed landscape gardener Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1715-1783) was a leading proponent of this naturalistic approach, which shunned the French-style formal gardens of old (think neatly trimmed lawns, elaborately shaped box hedges, and geometric gravel paths) in favor of serpentine paths that meandered past romantic-looking lakes, rustic clumps of trees, and artfully crumbling follies. This new style of garden frequently also featured a picturesque hermitage constructed of brick or stone, or even gnarled tree roots and branches. Many were decorated inside with shells or bones to create a suitably atmospheric retreat.

With the new fashion for building hermitages in country estates, the next logical step was to populate them with an actual hermit. It’s not clear who first started the trend, but at some point in the early 18th century, having a resident hermit quietly contemplating existence—and occasionally sharing some golden nugget of wisdom with visitors—came to be seen as a must-have accessory for the perfect garden idyll.

Real hermits were hard to find, so wealthy landowners had to get creative. Some put advertisements in the press, offering food, lodging, and a stipend for those willing to adopt a life of solitude. The Honorable Charles Hamilton placed one such ad after buying Painshill Park (an estate in Cobham, Surrey) and extensively remodeling the grounds. Hamilton created a lake, grottoes, Chinese bridge, temple, and a hermitage on his estate, then placed an ad for a hermit to live there for seven years in exchange for £700 (roughly $900, or $77,000 in today’s money). The hermit was not allowed to speak to anyone, cut their hair, or leave the estate. Unfortunately, the successful applicant was discovered in the local pub just three weeks after being appointed. He was relieved of his role and not replaced, perhaps demonstrating the difficulty of attracting a serious hermit.

One of the more famous Georgian hermits was Father Francis, who lived at Hawkstone Park in Shropshire in a summer hermitage made with stone walls, a heather-thatched roof, and a stable door. Inside, he would sit at a table strewn with symbolic items, such as a skull, an hourglass, and a globe, while conversing with visitors, offering spiritual guidance and ponderings on the nature of solitude. So popular was the attraction of a meeting with a real-life hermit that the Hill family, who owned the park, were obliged to build their own pub, The Hawkstone Arms, to cater to all the guests.

But while some estate owners struggled to find a good hermit, taking on the role did have some appeal, as evidenced by this 1810 ad in the Courier:

“A young man, who wishes to retire from the world and live as a hermit, in some convenient spot in England, is willing to engage with any nobleman or gentleman who may be desirous of having one. Any letter addressed to S. Laurence (post paid), to be left at Mr. Otton's No. 6 Coleman Lane, Plymouth, mentioning what gratuity will be given, and all other particulars, will be duly attended.”

Sadly, it is not known whether or not the would-be hermit received any replies.

When a nobleman was unable to attract a real hermit to reside in his hermitage, a number of novel solutions were employed. In 1763, the botanist Gilbert White managed to persuade his brother, the Reverend Henry White, to temporarily put aside his cassock in order to pose as a wizened sage at Gilbert’s Selborne estate for the amusement of his guests. Miss Catharine Battie was one such guest, who later wrote in her diary (with a frustrating lack of punctuation) that “in the middle of tea we had a visit from the old Hermit his appearance made me start he sat some with us & then went away after tea we went in to the Woods return’d to the Hermitage to see it by Lamp light it look’d sweetly indeed. Never shall I forget the happiness of this day ...”

If an obliging brother was not available to pose as a hermit, garden owners instead might furnish the hermitage with traditional hermit accessories, such as an hourglass, book, and glasses, so that visitors might presume the resident hermit had just popped out for a moment. Some took this to even greater extremes, putting a dummy or automaton in the hermit’s place. One such example was found at the Wodehouse in Wombourne, Staffordshire, England [PDF], where in the mid-18th century Samuel Hellier added a mechanical hermit that was said to move and give a lifelike impression.

Another mechanical hermit was apparently used at Hawkstone Park to replace Father Francis after his death, although it received a critical review from one 18th-century tourist: “The face is natural enough, the figure stiff and not well managed. The effect would be infinitely better if the door were placed at the angle of the wall and not opposite you. The passenger would then come upon St. [sic] Francis by surprise, whereas the ringing of the bell and door opening into a building quite dark within renders the effect less natural.”

The fashion for employing an ornamental hermit was fairly fleeting, perhaps due to the trouble of recruiting a reliable one. However, the phenomenon does provide some insight into the growth of tourism in the Georgian period—the leisured classes were beginning to explore country estates, and a hermit was seen as another attraction alongside the temples, fountains, and sweeping vistas provided in the newly landscaped grounds.

Today, the fascination with hermits still exists. At the end of April 2017, a new hermit, 58-year-old Stan Vanuytrecht, moved into a hermitage in Saalfelden, Austria, high up in the mountains. Fifty people applied for his position, despite the lack of internet, running water, or heating. The hermitage, which has been continuously inhabited for the last 350 years, welcomes visitors to come and enjoy spiritual conversation with their resident hermit, and expects plenty of guests.