By Caity Weaver

Illustrations by Celine Loup

The name Gertrude sounds hard—and that’s intentional. It comes from the Germanic roots ger (“spear”) and þruþ (“strength”). No wonder ladies with the moniker are brutish, unapologetic enforcers! The next time you’re going into battle, make sure you have one by your side.

1. The Gertrude Who Made Boxcars Exciting: Gertrude Chandler Warner

Born on April 16, 1890, Gertrude Chandler Warner grew up across the street from the Putnam, Conn., train station; the tracks were so close that her family’s windowsills were constantly covered in soot from the trains. As children, Warner and her two siblings spent their free time spying on trains from their windows, and they quickly became fascinated by the bare-bones living quarters housed in cabooses.

By her sophomore year, Warner was forced to drop out of high school due to poor health. But during World War I, when many of her school district’s teachers were called to serve overseas, she was asked (“begged,” as she told it) to take up a position teaching first grade. Despite her lack of experience, Warner accepted the job and took to it well—so well she continued to teach for the next 32 years.

It was the combination of all these things—Warner’s train-filled childhood, her love of teaching, and, most importantly, her recurring health problems—that led to the creation of one of the most beloved series of children’s books. The conceit of the Boxcar Children came to Warner one day when she was home sick from her teaching job. Confined to her bed, she decided to write a story to share with her students upon her return to class. Though she’d already published a few educational works, including a children’s astronomy guide, this time Warner decided to create a fictional world with young protagonists, and she crafted an adventure about four siblings who set up shop in a boxcar. To keep the kids’ attention, she did something bold: She cut out the parents.

This seemingly innocent act of editing brought plenty of ire. Librarians criticized Warner for glamorizing the mystery-solving lifestyle of unaccompanied minors. But Warner brushed off the remarks and stood firm. She knew a big part of the reason that children loved the books was that there were no pesky adults reminding Henry, Jessie, Violet, and Benny to wash their hands. Or to put on a sweater before going outside. Or to be careful when investigating that case of suspected arson near the family uranium mine (Boxcar Children #5, Mike’s Mystery).

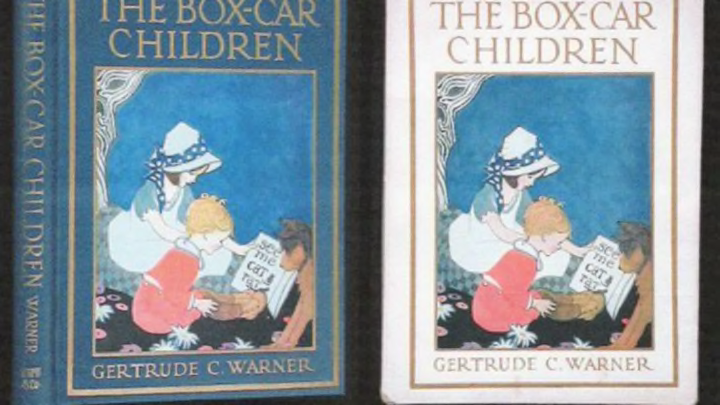

The first version of Warner’s book was published by Rand McNally in 1924 as The Box-Car Children, but it wasn’t until 1942, when another publisher released a simplified version of the text—aimed at poor readers and children learning English—that the series took off. Today, there are more than 150 Boxcar books, including both mysteries and “specials.” Only the first 19 books in the series were written by Warner herself, each one personally revised by the author at least four times. A stickler for details, Warner kept editing until each book said just what it needed to. In 1979, Warner died in the same town she’d grown up in, unmarried with no children. Her book series lived on, Baby-Sitters Club–style, with story lines updated by a team of ghostwriters. In 2012, the Boxcar children even got their own after-the-fact prequel: the sign of a true literary juggernaut.

2. The Gertrude Who Built Iraq: Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell

There's an old photo of 1921’s Cairo Conference that perfectly captures the era’s colonial mood: Three dozen mostly white men are positioned, formal-portrait-style, around a set of stairs, their serious mugs framed by a backdrop of lush palm fronds. Out front, a supine lion cub swats at a blurry shape, possibly a hyena.

The conference had been called out of necessity. One year earlier, unhappy Iraqis had set aside their Sunni and Shia differences to stage an uprising. The revolt was unsuccessful, but the fracas proved expensive enough that the British decided to rethink their Middle East strategy. Delegates to the summit included luminaries such as then-Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill and his special adviser T. E. Lawrence.

But there’s one figure in the pack that stands out: a pale, thin woman in a fur stole and wide-brimmed hat. This is Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell, the woman responsible for drawing the borders of Iraq. Churchill and Lawrence of Arabia? They’re just her coworkers.

Born in 1868 to the sixth-richest family in England, Gertrude Bell displayed a fierce intelligence at a young age. At 17, the gutsy redhead was one of the few women admitted to Oxford University, where she became the first woman to earn a first-class-honors degree in modern history. After graduating, Bell traveled the globe hunting adventure. She found it, repeatedly.

In 1902, she survived 53 hours hanging off a rope on the Bernese Alps’ highest peak during a blizzard. She taught herself Persian and trekked through Iran, taking photos and publishing a travel book about the experience. She picked up Arabic as she surveyed the Arabian Desert by camel, documenting ancient ruins and cultivating friendships with tribal leaders and kings.

Before long, the British government realized she could be an asset. The brassy adventurer had acquired an extraordinary amount of rare and valuable knowledge—from deciphering the region’s complicated tribal politics (something governments had been struggling to figure out) to mapping the land’s geographic features. In 1915, Bell became the first female officer hired by British military intelligence. Working under the vague title “adviser” and tapped to collect information as a British spy, she was placed on staff alongside T. E. Lawrence at the Arab Bureau in Cairo. Two years later, she was installed in Baghdad under British high commissioner Percy Cox—a position that would catapult her into the thorny task of nation-building. Bell was up for the challenge.

In 1921, after the devastating Sunni-Shiite revolt, Bell and her former Arab Bureau colleagues found themselves at the Cairo Conference, where the chief goal was to determine the most British-friendly political and geographical structure for the country that would become Iraq. Bell led the charge, plotting territorial boundaries to fit British needs. The lines she drew respected tribal borders while ensuring the new state would be rich in oil. As she worked to finish the map, the conference handpicked the new nation’s first king: a non-Iraqi named Faisal bin Hussein.

Installing a puppet king proved disastrous. Despite ties to Mecca— his father was sharif of Mecca, and he hailed from a long line of Hashemite rulers—Faisal was regarded as little more than a foreign monarch installed by a foreign monarchy. In fact, prior to becoming king, he had never traveled to the region. He relied on Bell for explanations on everything from local business practices to the customs of Iraq’s nomadic tribes.

Despite the obvious challenges, Bell defended the group’s choice, writing several months after the conference: “I don’t for a moment hesitate about the rightness of our policy. We can’t continue direct British control, though the country would be better governed under it.”

Still, the work wore her down. For a plucky woman who’d spent her life breezing through challenges, waltzing through conflict-ridden deserts and holding her own in the company of fierce intellectuals, nation-building took its toll. As she told her father, “You may rely upon one thing—I’ll never engage in creating kings again; it’s too great a strain.” Instead, she turned her energy to another cause: preserving the region’s cultural heritage. Always an archaeologist at heart, Bell fought to keep Mesopotamian artifacts in Iraq instead of allowing them to be whisked off to foreign museums. She even created an endowment to fund future digs in Iraq. In 1926, Bell opened the Baghdad Archaeological Museum. That same year, she passed away at age 57. The shaky monarchy Bell helped install lasted two generations before being brutally overthrown in a coup d’etat in 1958. The lines she drew on maps lasted longer: The Iraq boundaries Gertrude Bell created are still used to this day.

3. Gertrude Stein: The Gertrude Who Vouched for Picasso

Gertrude Stein’s Paris apartment was “smaller than most people’s dining rooms.” Chairs littered the floors and lined the edges of tables. They were clustered in groups and shoved into corners. But all those chairs had a purpose—they let visitors know it was OK to linger, whether you hoped for discussion or simply wanted to savor the view. The walls, after all, were the real attraction. Walking into Stein’s dark living room, visitors were confronted with hundreds of paintings jammed frame to frame—all purchases, trades, and gifts from Stein’s friends. Since her apartment didn’t initially have electric lighting, visitors lit matches to catch a better glimpse of the artwork in the corners. Though many of the artists were unknown then, today the names—Picasso, Cézanne, Matisse, Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec—carry a little more cachet.

Stein, a Pennsylvania native who gained fame as a Left Bank lesbian, was in the vanguard of the avant-garde in the early 20th century. After moving to France at age 29, Stein began assembling one of the most important early collections of modern art. Today, many regard the tiny apartment at 27 Rue de Fleurus as the world’s first modern art museum.

But Stein was more than a collector and admirer—her force of personality was instrumental in fanning the fledgling movement. As a champion of experimental painting styles, as well as a gifted networker, she encouraged friends and people of importance to buy in. On Saturday evenings, she opened her apartment to international artists, dealers, and curious members of the general public, fueling enthusiasm and intrigue. Her one stipulation: Everyone was welcome so long as they came with a reference in hand.

And everyone came. As Stein once wrote, “Matisse brought people, everybody brought somebody, and they came at any time and it began to be a nuisance, and it was in this way that Saturday evenings began.” Ironically, Stein did too good a job of promoting the modern art movement. As international dealers embraced the ideal, the prices of modern impressionist works rocketed. Before long, Stein could no longer afford to buy new pieces and was instead forced to hustle for additions to her gallery—acquiring paintings as gifts or through trade.

Stein wasn’t simply a promoter; her writings played an important role in the modernist movement as well. In 1903, a decade before James Joyce began writing Ulysses, Stein started the first major modern experimental novel in English: the nearly 1,000-page masterpiece The Making of Americans: Being a History of a Family’s Progress. The book, which tells the story of a family without the use of plot, dialogue, or action, is often described as a literary companion to Cubism. In the words of Metropolitan Museum curator Rebecca Rabinow, “She began to deconstruct the written word in the way she felt that Picasso was beginning to deconstruct the visual motif.” That she wrote in longhand and never revised the work is indicative of Stein’s assuredness of voice and opinion.

Stein passed away from stomach cancer at the age of 72, with her partner, Alice B. Toklas, by her side. Reflecting on her life, Stein said, “I always wanted to be historical, from almost a baby on.” Indeed, she was. Stein provided the fierce support the modernist art movement needed in its earliest stages. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s first Picasso came from Stein’s collection. And while Stein’s legacy in the art world is undeniable, her impact on language is just as profound. Stein’s 1922 short story “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene” is generally thought to contain the first published instance (indeed, the first 136 published instances) of the word "gay" to mean homosexual.

4. The Gertrude Who Fought the System: Gertrude Simmons Bonnin

The details in Gertrude Simmons Bonnin’s essay “The School Days of an Indian Girl” are brutal: “I remember being dragged out, though I resisted by kicking and scratching wildly. In spite of myself, I was carried downstairs and tied fast in a chair. I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids. Then I lost my spirit.”

Bonnin, popularly known as Zitkala-Sa (“Red Bird”), was one of the first Native American authors whose work was published without passing under the pen of a white interpreter or translator. Throughout her life, Zitkala-Sa struggled with her mixed heritage. She was born in 1876 to a full-blooded Sioux woman and a white man. But it was more complicated than that: Zitkala-Sa was a Yankton Sioux born on a Sioux reservation, with a German given name and a Lakota nom de plume. At age 7, she was lured by Quaker missionaries (with promises of plentiful red apples) to White’s Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Ind. It was there that her long braids were sliced off—and that she learned to write in English.

In 1899, after earning a scholarship to Earlham University in Indiana, where she studied violin, then spending two years at the New England Conservatory, Zitkala-Sa accepted a position as a music teacher at Pennsylvania’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School. But she was horrified by the institution’s underlying philosophy. As the school’s founder Richard Pratt was spouting phrases like “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” Zitkala-Sa began writing political essays criticizing the practices.

She bristled at the notion of white educators forcing native children to relinquish their cultural identities. Unsurprisingly, her writings led to a strained relationship with the assimilation schools that had taught her to write in the first place. Her stint at Carlisle didn’t last, but her fury did.

In 1916, Zitkala-Sa was elected secretary of the Society of American Indians, the first self-run American Indian rights organization, and she quickly made her influence felt. She persuaded the General Federation of Women’s Clubs to establish an Indian Welfare Committee, and later cowrote an investigation into the government’s mistreatment of tribes. Not only did the group uncover vast mismanagement within the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but it revealed how corporations had been systematically defrauding American Indians in Oklahoma to gain access to oil-rich lands. The reports also harshly criticized the administration of the schools as “grossly inadequate.” Children were being abused for refusing to pray in the Christian way and punished for clinging to their heritage.

Ultimately, the investigations inspired new school legislation and helped to give land management rights back to American Indians. But Zitkala-Sa knew she could do more. In 1926, she founded the National Council of American Indians to help lobby for American Indian legal rights.

Zitkala-Sa’s lifework was dedicated to protecting and preserving native culture, while helping American Indians assimilate into the mainstream. But in all her activism, she never gave up music. Zitkala-Sa died in 1938 at the age of 61, the same year her opera “Sun Dance” debuted on Broadway. The show she cowrote, one of the first to spotlight American Indian themes, received critical acclaim. Today, she’s buried at Arlington National Cemetery, alongside her military veteran husband.

This article originally appeared in mental_floss magazine. You can get a free issue here.