You know the Yellow Kid: that baby-faced, buck-toothed street urchin who graced comic strips in the latter half of the 1890s. He was created by Richard Outcault, who later went on to create the equally successful Buster Brown and his little terrier Tige.

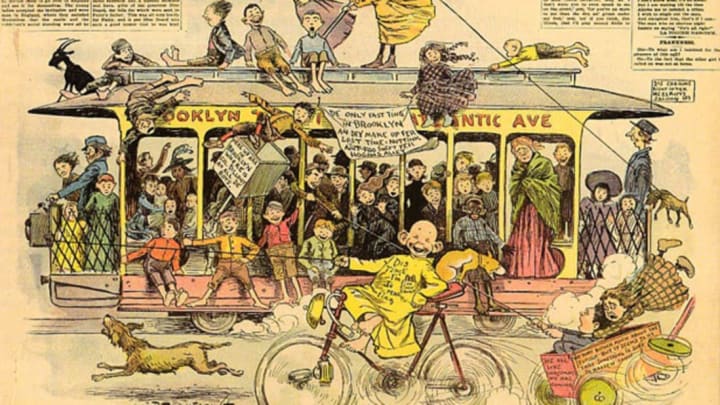

The Kid, whose full name was Mickey Dugan, first appeared in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World in 1895, one of a cast of characters in a strip called Hogan’s Alley. He soon became better known as the “Yellow Dugan Kid” for the omnipresent over-sized yellow nightshirt which bore his dialogue: quippy observations in a broad New York dialect.

As the Kid’s popularity rapidly grew, the strip’s presence actually increased paper sales for the World. And the capitalization didn’t stop there. Soon there was a Yellow Kid version of everything, from playing cards, pins, dolls, and ice cream, to bottle openers, sheet music, even cigarettes. Historians cite the Yellow Kid as the first example of modern merchandizing, a success which many attribute to the fact that he was a children’s character marketed to appeal to adults––a youthful anti-establishment symbol packaged by the establishment itself for mass consumption. (Not unlike the Kid’s fellow yellow superstars, Bart Simpson and SpongeBob SquarePants. Coincidence?)

In 1896, William Randolph Hearst offered Outcault an outrageously high fee to bring the Kid over to his New York Journal. Outcault accepted, a move that fueled the already heated rivalry between Pulitzer and Hearst. Pulitzer hired artist George Luks (an Ashcan School painter better known for his realistic depictions of New York City street life) to continue drawing Hogan’s Alley, featuring a knock-off Yellow Kid. Outcault attempted to submit a Yellow Kid copyright with the Library of Congress, writing, “his costume however is always yellow, his ears are large he has but two teeth and a bald head and is distinctly different from anything else.” He later learned that a clerical loophole had only allowed him to copyright the term “The Yellow Kid.”

In the months that followed, both Pulitzer and Hearst fought to give their competing Yellow Kids more and more page space. To many critics, the so-called “Battle of the Yellow Kids” represented a trend in the decline of journalistic integrity, of which both the World and the Journal had been guilty for years. One vocal critic, New York Press editor Ervin Wardman, had tried many times to pin a name on the papers’ sensationalistic, exaggerated, ill-researched, and often untrue reporting, unmemorably calling it “new journalism” and “nude journalism.” When the competing papers finally sunk so low as to replace news content with comic strips, he had his name: “Yellow-Kid Journalism,” which was eventually shortened to “Yellow Journalism.” The Kid’s symbolism fits the term still today: slap-dash journalism aimed at the kid in all of us.

Primary image courtesy of The Yellow Kid on the Paper Stage.