To become an Olympic hero in our book, it takes more than athleticism. Whether they were training in an internment camp or somersaulting with one leg, these athletes deserve infinite points—regardless of whether they medalled or not.

1. Tamio “Tommy” Kono // Weightlifting

A scrawny, asthmatic child, Tamio “Tommy” Kono developed his weightlifting physique in the most unlikely place—a Japanese internment camp. During World War II, he and his family were forced from their home in San Francisco and moved to a detention center in the California desert. For three and a half years, they endured brutal conditions along with other Japanese immigrants. Although the situation was terrible, the climate wasn't. The desert air agreed with Tamio's lungs, and he started lifting weights to pass the time.

After the war, Kono kept training, and within a decade, he was the lynchpin of the U.S. national weightlifting team. Despite his family's detention, he lifted for the Americans. Using his ability to raise and lower his weight quickly, Kono helped the team fill gaps in its roster. During his career, Kono lifted competitively at weights ranging from 149 pounds to 198 pounds. To bulk up, he'd devour six or seven meals a day, and to slim down, he'd “starve” himself with three meals a day. He won his first gold as a lightweight during his Olympic debut in 1952, his second as a light heavyweight in 1956, and then a silver as a middleweight in 1960. All in all, he set seven Olympic records and 26 world records. Plus, he went on to become Mister Universe three times.

2. Lis Hartel // Equestrian

In 1944, Danish horseback rider Lis Hartel contracted polio while pregnant. Although the illness left her almost totally paralyzed, she gave birth to a healthy baby girl. She also kept training for her event—equestrian dressage. By 1947, she was riding again, even though she couldn't use the muscles below her knees. Despite needing help mounting and dismounting her horse, she competed for Denmark at the 1952 Games, winning a silver medal in a sport that was almost entirely dominated by men. In an indelible image of Olympic sportsmanship, Swedish gold medalist Henri Saint Cyr helped Hartel onto the platform at the awards ceremony. In the following years, Hartel kept on riding and won another silver at the 1956 Games.

3. Spyridon Louis // Marathon

While planning the first modern Games in Athens in 1896, French historian Michel Breal wanted to come up with an event that linked the competition to its ancient roots. He suggested a footrace that was the distance from Athens to Marathon, because a messenger had once supposedly sprinted between the two cities to spread news of a Greek military victory. The Greek people were captivated by the notion of a race with such strong ties to their country's history, and they become obsessed with dominating the event.

While the other nations barely prepared for the competition, the Greeks held two qualifying trials to choose their entrants. Except for the Greek runners, only one other contestant had run a full marathon before the Olympic Games. On the day of the race, the lack of proper training quickly took its toll. By the halfway point, runners started dropping like flies.

After nearly three hours, fans at the finish line learned that a Greek runner named Spyridon Louis had taken the lead, despite stopping along the way for a glass of wine. Greece's Prince George and Crown Prince Constantine got so excited that they joined Louis for his last surge to the finish line. Louis, a peasant farmer, quickly became a national hero, and his name even entered the Greek vernacular. The term egine Louis, which translates as “become Louis,” is still used to mean “run quickly.”

4. Teófilo Stevenson // Boxing

Cuban boxer Teófilo Stevenson burst onto the heavyweight scene at the 1972 Munich Games by knocking down his first opponent in just 30 seconds. He was a force in the ring, and commentators often joked that the “honor” of facing him should go to the loser—not the winner—of previous matches.

After Stevenson cakewalked his way to the gold in 1972, boxing promoters clamored for the Cuban to go pro, but he resisted. He believed passionately in the Cuban revolution and preferred to fight on behalf of his country. After he nabbed another gold at the 1976 Montreal Games, promoters became even pushier. Stevenson passed up millions of dollars and was hailed as a national hero for his convictions. Then he picked up his third straight gold in 1980, at age 28. After retiring, Stevenson worked as a boxing consultant in Cuba, earning about $400 a month. When asked about all the money he turned down, he often replied, “What is a million dollars against 8 million Cubans who love me?”

5. G. Alberto Braglia // Gymnastics

Although professional athletes can compete in certain Olympic events today, the modern Games were founded on the purity of amateurs competing solely for the glory. However, this often forced star athletes out of the competition just for taking money to make ends meet. Legendary track-and-field champion Jim Thorpe, for example, lost his amateur status for earning $35 a week in minor-league baseball games.

Italian gymnast G. Alberto Braglia's “professional” adventures were even more pitiable. After winning the all-around gymnastics gold at the 1908 Games, Braglia hit upon hard financial times. So, he turned to the place best-suited for small, athletic fellows—the circus. Performing as the Human Torpedo, Braglia delighted audiences across Europe with his daredevil stunts. In the process, he broke his shoulder and several ribs [PDF].

Irked by his stint in the circus, Italy's governing body for gymnastics declared that Braglia had forfeited his amateur status. Just like that, his Olympic days were over. Fortunately, cooler heads realized that being a human torpedo wasn't quite the same as being a professional gymnast, and Braglia regained his amateur status in time for the 1912 Games in Stockholm. There, the Italian wonder picked up two more golds. After the Games, he returned to the circus, where he enjoyed a long and successful career.

6. Lawrence Lemieux // Sailing

At the 1988 Games in Seoul, Canadian sailor Lawrence Lemieux was moving along at a quick clip, even though the seas were exceptionally rough. About halfway through the race, he seemed to have a firm grip on the silver medal when disaster struck.

Lemieux heard the cries of two Singaporean sailors competing in a different event nearby. One of them was clinging desperately to his boat, which had capsized under the 6-foot waves. The other had drifted 50 feet away, swept off by the currents. Instead of staying in his race, Lemieux set course for the sailors and pulled them out of the water. His hope for a medal all but dashed, Lemieux waited for rescue boats to arrive. By the time they did, he'd fallen to 23rd place. But Lemieux's bravery did not go unrewarded. The Olympic committee gave him the Pierre de Coubertin medal, a special award for sportsmanship.

7. Shun Fujimoto // Gymnastics

The Japanese men's gymnastics team won gold at every Olympic Games from 1960 to 1972. So when the 1976 Games began, capturing a fifth straight gold was a matter of national pride.

Things started to come apart, however, when gymnast Shun Fujimoto felt something pop in his leg during the floor exercise. He knew he'd broken his kneecap, but hesitated to tell his coaches for fear of being pulled from competition. Knowing that his team needed every tenth of a point to win, Fujimoto decided to downplay the injury. He dusted himself off and hopped on the pommel horse, scoring a 9.5 despite the searing pain in his knee. Fujimoto later credited his injury with helping him to focus, because he knew the slightest error could have caused permanent damage. “I was completely occupied by the thought that I could not afford to make any mistakes,” he said.

Following the pommel horse was Fujimoto's strongest event—the rings. For his dismount, he flew through the air in a triple-somersault and made a near-perfect landing with clenched teeth and tears in his eyes. The judges awarded him a 9.7, a personal best. After sticking the landing, Fujimoto collapsed from pain. Even then, he only withdrew from the competition after doctors told him he would risk permanent disability by continuing. Fujimoto's teammates rallied around their friend's gutsy performance and edged out the Soviets for the gold.

8. Cassius Clay // Boxing

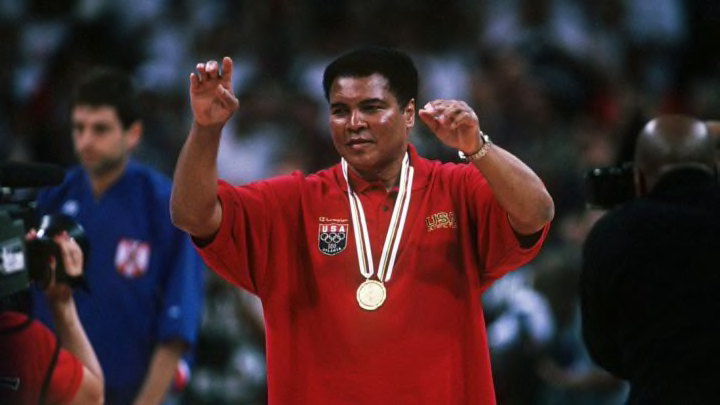

Before Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali, he was a cocky 18-year-old boxer at the 1960 Games in Rome. His masterful performance in the ring won him the gold, but his friendliness and chatty demeanor won him the hearts of journalists. Hoping to capitalize on Clay's loose tongue, the Soviet press tried to bait him into talking trash about America. One Soviet reporter asked him how he felt about being barred from certain restaurants back home, and Clay quickly responded, “Russian, we got qualified men working on that problem. We got the biggest and the prettiest cars. We get all the food we can eat. America is the greatest country in the world.”

After Clay returned home to Kentucky, he proudly wore his gold medal around his neck. But his American pride didn't last long. In Louisville, a whites-only restaurant refused to serve him, and a white gang made the mistake of trying to attack him. After the incidents, the medal lost its luster for Clay. According to popular legend, he reacted by abruptly chucking it into the Ohio River. Four decades and one Civil Rights movement later, the Olympic committee gave Ali a replacement medal during the 1996 Games in Atlanta.

9. Nawal El Moutawakel // Track and Field

Talk about Cinderella stories. After spending her childhood running through the streets of Casablanca, Morocco's Nawal El Moutawakel used her speed to earn a track scholarship to Iowa State University, where she won four individual Big Eight titles. In 1984, she became the only woman on the Moroccan team at the Los Angeles Olympics.

Moutawakel blew away her competition in the 400-meter hurdles, handing Morocco its first gold medal. At the same time, she also became the first Muslim woman and the first African woman to win a gold medal. As she ran her victory lap with a large Moroccan flag in hand, her elated countrymen back home poured into the streets of Casablanca in the middle of the night.

As a national hero, Moutawakel has used her celebrity to help other women in sports. Although Morocco largely supported her career, she knew women in other Islamic countries weren't so lucky. One of her greatest triumphs has been organizing a women's 10k race in Casablanca, which now draws tens of thousands of participants. As Morocco's Minister for Youth and Sports and a major player in the International Olympic Committee, Moutawakel led the task force that chose London as the site for the 2012 Games. She has summed up her triumphs by saying, “My athletic race was the 400-meter hurdles, but it has been a metaphor for my life ... You have to get over the hurdles and keep running.”

10. The 1932 Brazilian Olympic Team

For the Brazilian team, getting to the 1932 Los Angeles Games was an Olympic trial all its own. The Brazilian government was bankrupt, and it couldn't afford to pay for the team's expenses. So, as Sports Illustrated reported, the athletes traveled via coffee barge, stopping at ports between Brazil and Los Angeles to peddle roasted beans. All they needed was to sell the 50,000 bags on board.

Unfortunately, the team made only $24. At the time, the tax to enter the United States was $1 per person, meaning only 24 members of the squad were able to leave the ship. The other 45 teammates had to set sail for the Pacific Northwest to try to unload the rest of the coffee.

Sadly, the athletes who did make it to the Games didn't fare particularly well. After losing to Germany 7-3 in water polo, the Brazilian team jumped out of the pool and started attacking the referee. The police pulled the Brazilians off the battered official, and the water polo team was disqualified from the rest of the Olympics.

11. Mildred “Babe” Didrikson // Track and Field

When the Los Angeles Olympics rolled around in 1932, a 19-year-old typist named Mildred “Babe” Didrikson faced an unusual problem. The rules dictated that an athlete could only enter three track-and-field events, and Didrikson had qualified for five. So, she simply picked the ones in which she already held world records—javelin, 80-meter hurdles, and the high jump.

Her first event didn't get off to an auspicious start. The javelin slipped from her hand and tore the cartilage in her right shoulder. For most athletes, that would have meant instant defeat, but Babe's compromised throw sailed more than 143 feet and set a new world record. Two days later, Babe set another world record in the 80-meter hurdles. She looked poised to sweep her events, but was disqualified in the high jump competition for diving headfirst over the bar, which was illegal at the time. She had to settle for silver.

Didrikson had an outsized personality to match her athletic prowess. Reportedly, she'd greet her opponents with the taunt “Yep, I'm gonna beat you.” And during training sessions for the Los Angeles Games, she would reportedly irritate her teammates by literally running circles around them while playing her harmonica.

The Babe's sports dominance didn't stop with track and field. In 1935, Didrikson picked up golf, and by 1950, she'd won every available women's title in the game. She's still considered one of the greatest golfers of all time, male or female. Never humble, Didrikson wrote in her autobiography, “My goal was to be the greatest athlete who ever lived.”

12. Boris Onishchenko // Fencing

We've all heard of marathon runners hitching rides and athletes dosing up on performance enhancers, but who knew Olympic chicanery could come in the form of hacking? During the fencing competition at the 1976 Games in Montreal, the electronic scoring system started giving Soviet Boris Onishchenko credit for hits even when he didn't make contact with his opponent. Turns out, the clever comrade had rewired his sword with a hidden circuit breaker so that he could give himself points at the touch of a button.

13. Shuhei Nishida and Sueo Oe // Track and Field

At the 1936 Berlin Games, Japanese pole vaulters Shuhei Nishida and Sueo Oe tied for second place. The teammates were offered the opportunity to have a jump-off for the silver medal, but the two friends declined out of mutual respect for one another. For the purposes of Olympic records, Oe agreed to the bronze while Nishida took the silver.

Upon their return to Japan, the teammates came up with a different solution. The pair had a jeweler cut their medals in half and fuse them back together, creating half-silver, half-bronze pendants. The “Medals of Friendship,” as they're now known in Japan, are enduring symbols of friendship and teamwork.

This article originally appeared in the July-August 2008 issue of mental_floss magazine; it has been updated for 2021