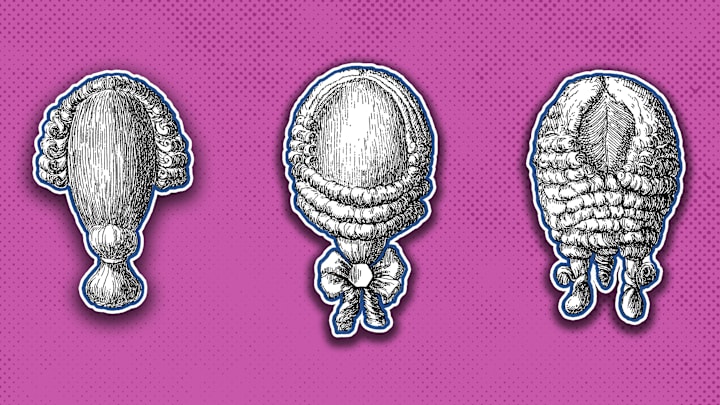

For nearly two centuries, powdered wigs—called perukes—were all the rage. The chic hairpiece would have never become popular, however, if it hadn’t been for a venereal disease, a pair of self-conscious kings, and poor hair hygiene.

It Started With Syphilis

The peruke’s story begins like many others—with syphilis. By 1580, the STD had become the worst epidemic to strike Europe since the Black Death. According to surgeon William Clowes, an “infinite multitude” of syphilis patients clogged London’s hospitals, and more filtered in each day. Without antibiotics, victims faced the full brunt of the disease: open sores, nasty rashes, blindness, dementia, and hair loss. Baldness swept the land.

At the time, hair loss was a one-way ticket to public embarrassment. Long hair was a trendy status symbol, and a bald dome could stain any reputation. When Samuel Pepys’s brother acquired syphilis, the diarist wrote, “If [my brother] lives, he will not be able to show his head—which will be a very great shame to me.” Hair was that big of a deal.

Cover-Up

And so, the syphilis outbreak sparked a surge in wigmaking. Victims hid their baldness, as well as the bloody sores that scoured their faces, with wigs made of horse, goat, or human hair. Perukes were also coated with powder—scented with lavender or orange—to hide any funky aromas.

Although common, wigs were not exactly stylish. They were just a shameful necessity. That changed in 1655, when the King of France started losing his hair.

Louis XIV was only 17 when his mop started thinning. Worried that baldness would hurt his reputation, Louis hired 48 wigmakers to save his image. Five years later, the King of England—Louis’s cousin, Charles II—did the same thing when his hair started to gray (both men likely had syphilis). Courtiers and other aristocrats immediately copied the two kings. They sported wigs, and the style trickled down to the upper-middle class. Europe’s newest fad was born.

The cost of wigs increased, and perukes became a scheme for flaunting wealth. An everyday wig cost about 25 shillings—a week’s pay for a common Londoner. The bill for large, elaborate perukes ballooned to as high as 800 shillings. The word bigwig was coined to describe snobs who could afford big, poofy perukes.

Wig Out

When Louis and Charles died, wigs stayed around; perukes remained popular because they were so practical.

At the time, head lice were everywhere, and nitpicking was painful and time-consuming. Wigs, however, curbed the problem. Lice stopped infesting people’s hair—which had to be shaved for the peruke to fit—and camped out on wigs instead. Delousing a wig was much easier than delousing a head of hair: You’d send the dirty headpiece to a wigmaker, who would boil the wig and remove the nits.

But by the late 18th century, the wig trend was dying out. French citizens ousted the peruke during the Revolution, and Brits stopped wearing wigs after William Pitt levied a tax on hair powder in 1795. Short, natural hair became the new craze, and it would stay that way for another two centuries or so.

A version of this story ran in 2012; it has been updated for 2023.