Many pioneering artists have endured abuse from critics and naysayers. But once in a blue moon, time brings acceptance and acclaim, making those early detractors look silly to future generations. Check out how the following works—whose ‘classic’ status now seems self-evident—were once butchered by the Simon Cowells of yesteryear.

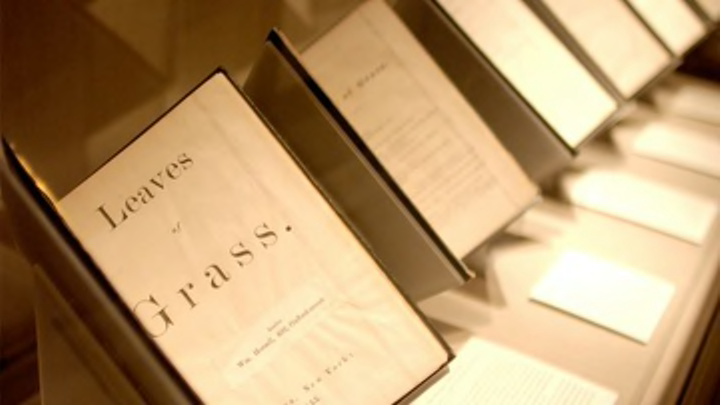

1. Leaves of Grass, by Walt Whitman (first pub. 1855)

Modern Status: “If you are American, then Walt Whitman is your imaginative father and mother, even if, like myself, you have never composed a line of verse… candidates for the secular Scripture of the United States…might include Melville's Moby-Dick, Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Emerson's two series of Essays and The Conduct of Life. None of those, not even Emerson's, are as central as the first edition of Leaves of Grass.” – From Harold Bloom’s introduction to the 150th anniversary edition

Early Reaction: Upon reading the newly published Leaves, Whitman’s boss at the Department of the Interior took offense—and gave his underling the axe.

*

Fellow poet John Greenleaf Whittier supposedly hurled his 1855 edition into the fire.

*

"A mass of stupid filth" -Rufus Wilmot Griswold, The Criterion, November 10, 1855

*

"It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass, only that he did not burn it afterwards." –Thomas Wentworth Higginson, The Atlantic, “Literature as an Art,” 1867

*

“… the book cannot attain to any very wide influence." –The Atlantic, January 1882

2. Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, by Ludwig van Beethoven (1824)

Modern Status: A mainstay of the Western classical canon, Beethoven’s 9th (composed when old Ludwig was deaf!) is believed by some to be the greatest piece of music ever written, and pretty much universally considered among his choicest works.

Early Reaction: “We find Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to be precisely one hour and five minutes long; a frightful period indeed, which puts the muscles and lungs of the band, and the patience of the audience to a severe trial…” –The Harmonicon, London, April 1825

3. Carmen, by Georges Bizet (1875)

Modern Status: One of the most beloved operas of all time, Bizet’s Carmen (1875) was savaged by the reviewers of its day, who regarded the opera’s flashy score and lurid subject matter with suspicion and hostility. Within a few years, however, the punters were going mad for its tempestuous love story, foreign setting and lush melodies—and over the next century it became one of the most oft-performed operas in the world. Sad to say, Bizet kicked the bucket before he could savor Carmen’s rise to glory.

Early Reaction: “The characters evoke no interest in the spectators, nay, more, they are eminently repulsive…” -Music Trade Review, London, June 1878

*

“As a work of art, it is naught.” –New York Times, October 1878

*

“The composer of Carmen is nowhere deep; his passionateness is all on the surface, and the general effect of the work is artificial and insincere.” –Boston Gazette, January 1879

4. Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville (1851)

Modern Status: “For me, Moby-Dick is more than the greatest American novel ever written; it is a metaphysical survival manual—the best guidebook there is for a literate man or woman facing an impenetrable unknown: the future of civilization in this storm-tossed 21st century.”

– Nathaniel Philbrick, Vanity Fair, Nov 2011

Early Reaction: When Melville died in 1891, Moby-Dick had moved a grand total of 3,715 copies…in 40 years! The below was typical at the time of the book’s release:

“…an ill-compounded mixture of romance and matter-of-fact. The idea of a connected and collected story has obviously visited and abandoned its writer again and again in the course of composition…Our author must be henceforth numbered in the company of the incorrigibles who occasionally tantalize us with indications of genius, while they constantly summon us to endure monstrosities, carelessnesses, and other such harassing manifestations of bad taste as daring or disordered ingenuity can devise...” -Henry F. Chorley, London Athenaeum, October 25, 1851

5. Wuthering Heights, by Emily Brontë (1847)

Modern Status: Back in horse-and-buggy days, critical consensus gave the nod to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as the best of the Brontë sister novels. But many book snobs nowadays prefer Emily’s Gothic romance Wuthering Heights. Regardless of which Bronte’s work you think would survive a steel-cage Battle-to-the-Death, Heights’ status as a landmark of Gothic romance and Brit Lit classic is in the vault. Plus it was crowned the greatest love story of all time in a 2007 poll of Guardian readers.

Early Reaction: “The general effect is inexpressibly painful. We know nothing in the whole range of our fictitious literature which presents such shocking pictures of the worst forms of humanity....” –Atlas, January 22, 1848

*

"How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery. It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors." –Graham's Lady Magazine

6. Ulysses, by James Joyce (1918)

Modern Status: Joyce’s notoriously difficult, stream-of-consciousness tour de force is synonymous with the modernist sensibility and spawned generations of Joycean scholars and societies. In 2000, the Modern Language Association appointed Ulysses as the single greatest novel of the 20th century.

Early Reaction: “In Ireland they try to make a cat clean by rubbing its nose in its own filth. Mr. Joyce has tried the same treatment on the human subject” –George Bernard Shaw

7. Animal Farm, by George Orwell (1945)

Modern Status: Appears on TIME magazine’s 100 best English-language novels (1923 to 2005) list

*

#31 on the Modern Library List of Best 20th-Century Novels

*

Wins retrospective Hugo Award in 1996

*

Included in the Great Books of the Western World

*

Estimated 25 million copies sold

Early Reaction: “It is impossible to sell animal stories in the USA.” –Publisher’s rejection

8. Endymion, by John Keats (1818)

Modern Status: Highlighting his flair for rhapsodic flights of sensual imagery, Keats’ meditation on beauty concerns a goddess’ love for a mortal. Now regarded as a primo example of the British poets’ romantic worldview, Endymion withstood the over-the-top critical onslaught leveled at it upon release and survived the test of time.

Early Reaction: "To witness the disease of any human understanding, however feeble, is distressing; but the spectacle of an able mind reduced to a state of insanity is of course ten times more afflicting. It is with such sorrow as this that we have contemplated the case of Mr John Keats. …The frenzy of the Poems was bad enough in its way; but it did not alarm us half so seriously as the calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy of Endymion. It is a better and easier thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; go back to the shop, Mr. John, back to `plasters, pills and ointment boxes.'" –John Gibson Lockhart (pen name “Z”) for Blackwood's Magazine (1818)

9. The Impressionists (mid- to late 1800s)

Modern Status: Impressionism’s success and popularity over the last century hardly needs rehashing—but it sure didn’t start out that way. “Impressionism” and “pointillism” were originally intended as derogatory terms. The practitioners of these styles quickly co-opted these coinages, however, and used them as a badge of honor.

At the so-called Salon des Refusés (“exhibition of rejects”) in 1863, a group of early impressionists, peeved by the Paris art establishment’s continued rejection of their work, exhibited thousands of paintings amid a storm of controversy and critical abuse. Now-famous paintings exhibited at the event include Manet's Luncheon on the Grass and James McNeill Whistler's Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, as well as priceless works by Pissarro and Sisley.

A few years later, Manet’s Olympia (which now occupies a place of honor in the Louvre) would cause an even bigger commotion upon public display. Many current art critics and historians consider Olympia his masterpiece—a view also held by the artist himself.

Early Reaction: “Someone should tell M. Pissarro forcibly that trees are never violet, that the sky is never the colour of fresh butter, that nowhere on earth are things to be seen as he paints them.” –Albert Wolff, Le Figaro (1876)

*

“Had he learned to draw, M. Renoir would have made a very pleasing canvas out of his 'Boating Party.'” –Wolff

*

“What is this Odalisque with a yellow stomach, a base model picked up I know not where, who represents [Manet’s] Olympia?” –Jules Claretie, L’Artiste

*

"Mr. Cézanne merely gives the impression of being a sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens." –Marc de Montifaud, L'Artiste, May 1874

10. Fred Astaire (1899 – 1987)

Modern Status: “…like Bach, who in his time had a great concentration of ability, essence, knowledge, a spread of music…Astaire has that same concentration of genius.” –Balanchine

*

“…simply the greatest, most imaginative dancer of our time.” –Nureyev

*

“What do dancers think of Fred Astaire? It's no secret. We hate him. He gives us a complex because he's too perfect. His perfection is an absurdity. It's too hard to face.” –Baryshnikov

Early Reaction: “Can’t act. Can’t sing. Slightly bald. Can dance a little.” –MGM Testing Director’s response to Astaire’s first screen test

This post originally appeared in 2012.