Former British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s memoir, A Journey, is sparking all sorts of picketing and protesting around the U.K., so we thought it might be a good time to take a look at a few presidential memoirs from this side of the pond. Here are a few things you might not have known about former presidents’ literary output.

Best Choice of (Possible) Ghostwriter

Getty Images

Ulysses S. Grant should have been on sound financial footing when he finished his second term in 1877. He was arguably the world’s most famous war hero, and he had been in the White House for eight years. In reality, though, his finances were anything but stable. Following a two-year trip around the world and a disastrous investment with a swindling banking partner, Grant found himself on the verge of bankruptcy; he even had to sell his Civil War mementos to pay off debts.

He still had access to that great presidential cash cow, the memoir, though. Mark Twain approached Grant about publishing the war hero’s memoirs with a plum deal that would give Grant 75% of the profits as royalties. Cash-strapped Grant had little choice but to accept Twain’s offer, and the Civil War-focused Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant hit stores in 1885.

Grant’s memoirs were an instant runaway hit. Twain’s company made the clever choice of employing former Union soldiers in full uniform as salesmen, and the book became one of the best sellers of the 19th century. Today, the book is considered by many to be the best presidential memoir ever written, but there’s some controversy over who actually did the bulk of the writing. Twain always claimed that he had only made slight edits to Grant’s text, but the prose was so strong that many suspected Twain himself had ghostwritten the book.

Sadly, Grant didn’t get to see the success of his book; he died shortly after its completion. But his widow Julia banked over $400,000 in royalties from the memoir.

Worst Financial Windfall

Getty Images

While today’s presidents are financially set for life from publishing and consulting gigs when they leave the Oval Office, just 57 years ago that wasn’t the case.

When Harry Truman’s term ended in 1953, he didn’t have any savings to speak of, and he felt taking a corporate job would cheapen the presidency. His only income was a $112-a-month pension from his days in the Army.

Truman decided that the best way to drum up some cash was to sell his memoirs, for which he got a $670,000 advance. By the time he paid taxes and his assistants, though, Truman only netted a few grand on the two-volume work. Eventually his financial straits grew so dire that Congress passed the Former Presidents Act in 1958 to guarantee annual pensions of $25,000 to former presidents.

Best Use of Revisionist History

Getty Images

History has judged James Buchanan pretty harshly; most scholars rank him among the worst presidents we’ve ever had. You know who was a bit more sympathetic in his appraisal of the failed Buchanan administration, though? James Buchanan. In 1866 Buchanan published the first-ever presidential memoir, the magnificently titled Mr. Buchanan’s Administration on the Eve of Rebellion.

In his book, Buchanan tried to set the record straight about his presidency. By the time Buchanan’s memoir came out, the Civil War had ended and Abraham Lincoln had become a national icon, so Buchanan attempted to liken his own policies to Honest Abe’s. Sure, Buchanan had opposed abolitionists and was considered to be a doughface—a Northerner with Southern sympathies—but in his mind, he was just like Lincoln and felt history would someday set the record straight. Unfortunately for Mr. Buchanan, it didn’t.

Most Honest Use of a Ghostwriter

Getty Images

Ronald Reagan was quick with a quip, and he dropped one of his best one-liners at the release of his 1990 memoir An American Life. Publisher Simon & Schuster held a press conference for the release of the book, which Reagan had supposedly penned “with the editorial assistance of Robert Lindsey." In truth, it sounds like Lindsey may have received only the slightest assistance from Reagan. The Gipper joked at the press conference, “I hear it's a terrific book! One of these days I'm going to read it myself.”

Worst Sales Loss at the Hands of a Spouse

Getty Images

Poor Gerald Ford just couldn’t win any respect. When his memoir A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford came out in 1979, his wife, Betty, also had a memoir on the stands, The Times of My Life. Betty gave her husband a t-shirt that read “Bet My Book Outsells Yours” for his birthday. To make the crummy gift even worse, she was right. At least Ford was in good company; Nancy Reagan’s memoirs also outsold her husband’s.

Quickest Read

Getty Images

Calvin Coolidge earned the nickname “Silent Cal” for being famously taciturn, and his memoirs weren’t uncharacteristically verbose. Coolidge takes the prize for the shortest presidential memoir—The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge comes in at a tight-lipped 247 pages.

Biggest Advance

Getty Images

Bill Clinton got an astounding $15 million advance from Knopf for his 900-page behemoth of a memoir My Life. When Clinton signed the deal, publishing analysts figured the book would have to sell upwards of 800,000 hardcover copies just to break even, but Knopf aggressively ordered a presidential-record-breaking first run of 1.5 million copies.

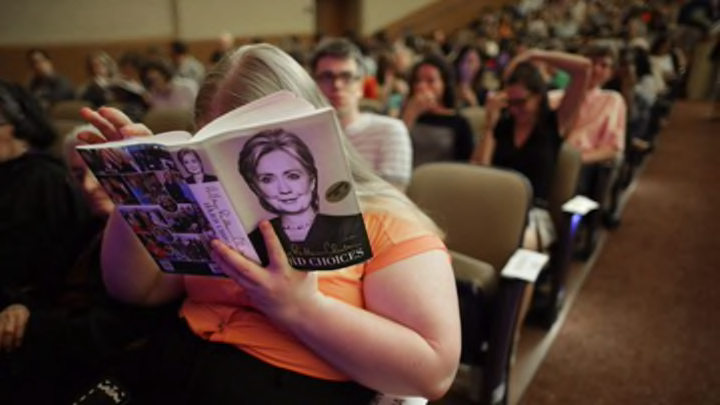

To give you a sense of perspective, Richard Nixon’s memoirs sold 330,000 and were considered a huge hit; to justify this advance, Bubba was going to have to really move some books. But as of 2008, Clinton had not just surpassed that monstrous advance; he had pocketed nearly $30 million from sales of My Life and his follow-up, Giving: How Each of Us Can Change the World. Hilary wasn’t doing so badly for herself in the publishing game, either. Her book Living History made her more than $10 million.

Longest Takedown of FDR

Getty Images

Like Buchanan, Herbert Hoover doesn’t get much love from historians, but he certainly stood up for himself. After leaving office in 1933 after what’s generally agreed was a fairly disastrous stint, Hoover needed 18 years to crank out the first tome of his mammoth three-volume memoir. His main goal? Explaining why his presidency wasn’t really a failure and bashing the policies of his successor, Franklin Roosevelt.

Among Hoover’s most memorable smears of FDR: “The effort to crossbreed some features of Fascism and Socialism with our American free system speedily developed in the Roosevelt administration." Take that, New Deal!