I live in Cleveland, which doesn't seem like a town where a bottle of water could go for $1,701. There's no Rodeo Drive here, no Hollywood sign, no posh salons promising the perfect poodle pedicure.

On the theory that there had to be something else in the water for it to cost $1701, the supplement search started with Beluga caviar and skipped through the alphabet past gold and saffron. Nothing. No clues whatsoever to explain how something so common could cost so much.

Had the label read, "Nectar of the Gods," maybe. But not a bottle of H20 sitting next to an ice bucket on top of an armoire in a hotel room occupied by a Cleveland Browns player during a preseason trip.

(Note to non-sports fans: The Cleveland Browns are an institution in my town and, on rare occasions, a pro football team.)

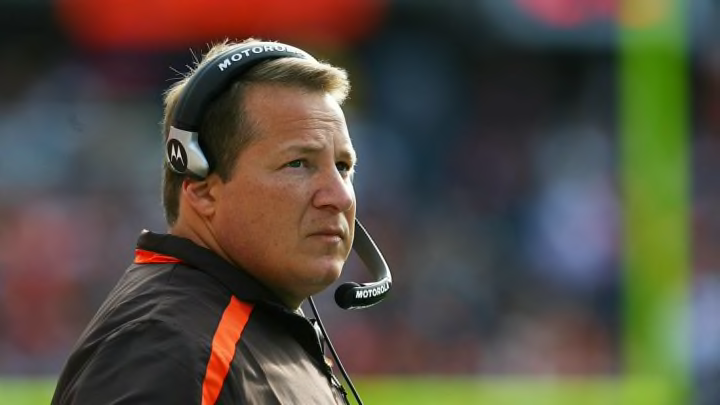

With the trip finished and the bill now in the hands of organizational number crunchers, Browns' head coach Eric Mangini learned that one of his players had checked out without paying for the water.

Mangini's next move fell right in line with all the control-freak, single-minded, my-way-or-the-highway football coaches of legend. He didn't tell payroll to subtract $3 from the player's next check. He levied a $1,701 fine—the maximum allowed under the Collective Bargaining Agreement.

That was my most recent reminder that football coaches—the driven, paranoid, contradictory lot of them—do (and say) the darndest things.

Basketball coach Bob Knight, who took a class or two as a student at Ohio State from the legendary football coach Woody Hayes, once said, "When they get to the bottom of Watergate, they'll find a football coach."

Well, close.

They found President Richard Nixon, a benchwarmer at Whittier College, who once recommended a play to Redskins' head coach George Allen. If there were a Mt. Rushmore of control freak coaches, one stone-faced expression would belong to Allen, who employed a man named Ed Boynton, whom sportswriters aptly nicknamed Double O Boynton—his job was to search the woods around the Redskins field looking for spies.

Lest any detail go unattended, Allen once had a scout chart the position of the sun to try to keep it out of the eyes of his punt-catchers.

(By the way, Allen did run the play Nixon suggested and it lost yards.)

Please Turn Off the Fireworks

The first NFL coach I spent serious time around was Dick Vermeil, who led the Philadelphia Eagles to Super Bowl XV, quit citing burnout a few years later, and then later won a title with the St. Louis Rams in his reincarnation.

When Vermeil opened his first training camp on July 4, 1976, he huddled his coaches in a room for meetings and film study that night. When darkness fell, explosions big and small erupted outside.

Vermeil hated anything he considered a distraction. He demanded to know what was going on. An assistant told him that not only was it the Fourth of July, it was the Bicentennial—a celebration of the country's 200th birthday. He was, after all, in suburban Philadelphia, a city that served as midwife in that birth.

"I don't care whose birthday it is," Vermeil railed, "Go tell them to turn it off."

While coaching at UCLA, Vermeil conducted interviews for his staff between midnight and 3 a.m. Those were his down hours.

In Phildelphia, he made daily lists every morning for his wife, his administrative assistant, his personnel man and himself. He slept in his office. On more than one occasion, as the reporter covering the Eagles for an afternoon paper, I'd call Vermeil in his office at 3 or 4 a.m. to check on something. He always answered the phone on the first or second ring, as if it were noon.

"What can I do for you?" he'd say.

After the first season, it became clear that Vermeil's tunnel vision about football prohibited even the slightest bit of working knowledge about almost all other topics. We'd have fun with that in the press corps, occasionally sliding a current event into the discussion just to elicit a blank stare.

My favorite Vermeil story came at practice one day. Workers were erecting scaffolding at one end of the stadium for the upcoming Rolling Stones concert. Hammers and drills were the background music of the day. That sort of distraction drove Vermeil wild.

When he walked over to where we stood for his post-practice press conference, someone mentioned the noise. Vermeil griped about the noise disrupting his practice.

"Dick, are you a fan of the Rolling Stones?" he was asked.

"I don't know much about them," Vermeil said. "But my kids read their magazine."

My only regret is that I never got to ask him about The Monkees. It is not out of the realm of possibility that he would've said, "Look, I've never been to the zoo."

When he showed signs of burning out, the Eagles GM along with Vermeil's wife urged him to set aside some time and meet with the team psychologist.

Carol Vermeil remembers her husband walking into the house after the appointment. "How'd it go?" she asked.

Said Vermeil, "Ah, it would take me a week to straighten that guy out."

Vermeil once waived a player at practice after the kid missed three blocks. The player, free agent, Mike Siegel, left the field disrobing as he went until he wore only a pair of shorts. If Vermeil noticed, he didn't say anything.

Vermeil once redid an entire playbook section because an assistant coach drew the circles and squares representing offensive and defensive players by hand. Vermeil insisted on using a stencil.

During Super Bowl XV when we were in New Orleans, the off-field story of the week was that Oakland defensive lineman John Matuszak had been seen out until all hours on Bourbon Street leading up to the game. Asked what he'd do if one of his players did the same, Vermeil huffed. "They be sent home to Philadelphia on the next plane, he said.

Oakland, with John Matuszak playing, came out loose and focused in Super Bowl XV, beating Vermeil's uptight Eagles, 27-10.

In a Sports Illustrated profile that writer Gary Smith did on Vermeil after his resignation, Carol Vermeil talked about how it was living with her husband.

"I'd say, "Dick, I cut off my arm today but I don't think it's too bad—and he wouldn't even blink," she said.

Great Moments in Football Coaching

October seems as good a time as any to celebrate (for lack of a better word) the American football coach for all his single-minded overwrought tunnel vision. In my 33 years of sports writing, here are a few who commanded my attention:

Joe Gibbs: The legendary Redskins coach is said to have asked his wife to tape dinner-table conversations so he could take the tapes to the Redskins' facility and catch up on what the family was doing.

Dale Christensen: You never heard of him, I'm sure. He was a Illinois high school football coach, who thought it would be a good idea before a playoff game to have his players see him get shot.

Christensen staged the phony shooting in the school cafeteria before a playoff game, ostensibly to motivate his players. Students understandably scrambled for cover after Christensen fell to the floor, fake blood covering his shirt. Two calls to police emergency numbers were made.

In the news account of the incident one player said "the shock of the idea we were going to die" overshadowed any point the coach had been trying to make. Go figure.

Woody Hayes: His sideline rants at OSU were famous, especially the one at the 1978 Gator Bowl that cost him his job after he punched a Clemson player. "When I look in the mirror in the morning, I want to take a swing at me," Hayes once said.

My favorite story about Hayes was just recently shared by a writer, who covered OSU football for the campus paper back in the day. Leonard Downie Jr. said last year that after OSU losses or ties, Hayes would conduct post-game interviews in the nude.

"He was an ugly guy," Downie said, "so it would clear out the locker room pretty fast."

Bear Bryant: Not that football coaches ever overestimate the importance of what they do, but the legendary Alabama coach once said, "If you want to walk the heavenly streets of gold, you gotta know the password, "Roll, tide, roll!"

Jon Gruden: Another NFL coach who, like Gibbs and Dick Vermeil, wore a lack of sleep as a badge of honor. In Tampa he was known as "Jon: 3:11." No, not because he was a ravenous reader of Scripture. But because that's when his alarm went off every morning.

John McKay: Consider McKay's inclusion on this list as an intermission. He wasn't like the others. His approach and especially his dry wit were antidotes for what ails some of football's most driven coaches.

Lots of people probably know the most famous quote attributed to him. His Tampa Bay Buccaneers were a winless and hapless expansion team. Asked after one horrid performance what he thought of his offense's execution, McKay said, "I'm all for it."

A lesser known McKay moment came after his USC team lost 51-0 to Notre Dame. Addressing his Trojans in the locker room, McKay said only, "All those who need showers, take them."

Lee Corso: (Extended Intermission) The former coach at Indiana and current ESPN analyst once said, "Hawaii doesnÃt win many games in the United States."

Lou Holtz: A misplaced college coach, Holtz came to the New York Jets and tried to line up players for the national anthem according to size. He wrote a team fight song to the tune of "The Caissons Go Rolling Along." He didn't last long for some odd reason.

Tom Coughlin: The Giants head coach has famously fined players for showing up early for meetings. Players are told to be there five minutes ahead of time. Four minutes early? Bam, fined.

As head coach of the Jacksonville Jaguars, he fined players for not wearing socks. Coaches could not wear sunglasses. He once fined two players who were hurt in a car accident while rushing to a team meeting, his reasoning being they would've been late anyway.

Nick Saban: Once turned down an invitation to dine with Geroge W. Bush because the time interfered with his practice schedule. OK, avoiding politicians doesn't reflect too badly on a fellow. But Saban also passed up a chance to play golf at Augusta National for the same reason. That's different. That's a man with a serious problem.

More Dick Vermeil: When the Eagles made the playoffs, CBS wanted to do an interview with Vermeil and his family at home around the Christmas tree. No chance. He hardly ever went home, choosing to sleep in his office. CBS got its interview—but only after it the family and the tree to his office.

Bear Bryant, Take 2: We leave you on this note. Bryant was once asked to contribute $10 to help bury a sportswriter.

According to legend, he said, "Here's a twenty, bury two."

If I'm still above ground, I'll see you in November.