When it comes to unearthing the ancient origins of humankind or solving the mystery of a vanished American colony, people want to believe. And that makes them easy targets of archaeological hoaxes. Practical jokers have fabricated “Viking” artifacts, “prehistoric” human remains, and “biblical” relics that have pulled the wool over the public’s eyes. Here are a few of these brazen bamboozles that remain notorious even today.

- The James Ossuary

- The Calaveras Skull

- Etruscan Terracotta Warriors

- Piltdown Man

- The Persian Mummy

- The Tiara of Saitaphernes

- Mississippi’s Dummy Mummy

- Cardiff Giant

- Michigan Relics

- The Heavener Runestone

The James Ossuary

This limestone box turned up in Israel in 2002, according to its owner, antiquities collector Oded Golan, who claimed it was the ossuary (a receptacle for bones) of Jesus’s brother James. The ossuary itself dates back to the 1st century, but an Israeli court determined that the inscription on it—“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”—was a modern forgery made to look old by the addition of a chalk solution. Nevertheless, the object continues to make the rounds in biblical museum exhibits.

The Calaveras Skull

In February 1866, gold miners in California found a human skull buried beneath a million-year-old layer of lava. It fell into the hands the state geologist, who said the skull represented the oldest known human being—and that humans had not evolved much in a million years, a claim that appealed to proponents of creationism. However, tests conducted at Harvard showed that the skull was of recent Native American origin. One of the original miners later admitted to planting the skull in the mine.

Etruscan Terracotta Warriors

The Metropolitan Museum of Art got taken several times by the Ricardis, a family of art forgers. Between 1915 and 1918, the family sold three large statues that they claimed were Etruscan to the museum: one titled Old Warrior, one called Colossal Head, which experts believed had been part of a 7-meter (23-foot) statue; and Big Warrior, which the museum purchased for $40,000 ($809,000 in today’s dollars). It wasn’t until 1960 that tests showed manganese, an ingredient not used by the Etruscans, in the statues’ glaze. A sculptor who had been involved in the forgeries then came forward and signed a confession that the pieces were all fakes.

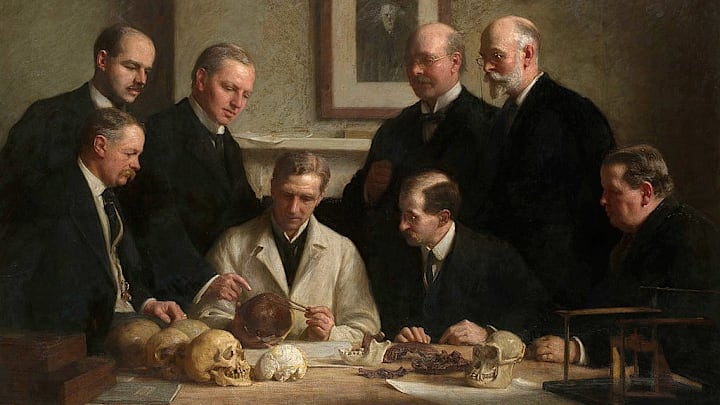

Piltdown Man

In 1912, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson contacted the National History Museum in London to report his discovery of a strange skull near the village of Piltdown in East Sussex, England. The museum’s Keeper of Geology, Arthur Smith Woodward, joined Dawson at the dig site and they uncovered additional bones and tools, which Smith Woodward later identified as belonging to a previously unknown human ancestor living 500,000 years ago—the alleged “missing link” in the evolutionary trajectory from ape to human. Beginning in 1949, however, scientists used new technology to determine the age of the artifacts, and concluded that the cranium couldn’t be more than 50,000 years old, while the jawbone wasn’t even human. It belonged to an ape species—likely an orangutan—and its teeth had been filed to look less simian. The hoaxer has never been identified.

The Persian Mummy

In 2000, Pakistani officials announced the discovery of a mummy in the region of Baluchistan. It was accompanied by objects that identified the body as Rhodugune, a daughter of King Xerxes I of Persia who lived in the 5th century BCE. The “Persian Princess” was displayed at the National Museum of Pakistan in November 2000, but studies eventually showed that the coffin was maybe 250 years old, the mat underneath the body was at most 5 years old and the woman had died only two years before. A murder investigation was then launched, but the identity of the woman was never confirmed. The body was buried in 2008.

The Tiara of Saitaphernes

The Louvre bought this regal artifact in 1896 because curators believed it had belonged to Scythian king Saitaphernes. Experts at the museum declared its provenance to be late 3rd century BCE or early 2nd century BCE, but quite a few art historians challenged those dates. It turned out that a skilled goldsmith had been commissioned to make the tiara for an archaeologist friend. The goldsmith was so good that it passed muster. The museum was extremely embarrassed when it learned the truth and hid the tiara from the public for years.

Mississippi’s Dummy Mummy

In the 1920s, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History bought a collection of Native American artifacts that included a decidedly anachronistic Egyptian mummy. In 1969, a medical student asked the museum for human remains to study and the museum allowed him to examine the mummy. He found that it was mostly papier-mâché, with a few animal rib bones thrown in to make it appear authentic. The “dummy mummy” remains a popular draw when it’s exhibited at the state capitol.

Cardiff Giant

This 10-foot-tall, alleged petrified man was discovered in 1869 by workers digging a well in Cardiff, New York. The giant was actually manufactured from a block of gypsum and shipped to a farm in Cardiff, where it was buried for a year before being found by the well builders. P.T. Barnum offered to buy it and was turned down, so he had his own built and claimed his was real and the Cardiff Giant was a fake. They were both proven fake in 1870.

Michigan Relics

Michigan resident James Scotford found the first of the so-called Michigan Relics, a casket inscribed with vaguely religious symbols, in a field in 1890. Over the next three decades, more than 3000 artifacts, including tools, cups, tablets, and figurines, would be unearthed across 16 counties in the state. Though contemporary scholars debunked the items as ancient objects almost immediately, Scotford and Michigan’s secretary of state, Daniel Soper, continued to conduct well-publicized digs and invited members of the public to join them. Invariably, the participants found more alleged relics. In 1911, however, Scotford’s stepdaughter told the press that she had witnessed him making the relics, finally putting to rest the conspiracy theories surrounding the items. The collection remains at the University of Michigan’s Museum of Anthropological Archaeology.

The Heavener Runestone

A colossal stone slab inscribed with what looked like Viking symbols, found near the the town of Heavener, Oklahoma, caught the public’s attention in 1923 when a citizen wrote to the Smithsonian asking for information about it. The institution claimed the inscriptions were runes, spawning decades of speculation about Viking settlers in the Midwest centuries before Leif Erikson landed on the coast of Newfoundland. Some scholars have suggested the stone represents a boundary marker and dates from 100 to 700 CE, based on the type of lettering. However, in 2015, a Swedish scholar examined the object and determined that it was most definitely not of Viking origin, based on the clear tool marks that would have been weathered and smoothed by time had the stone been carved more than a millennium ago. He also noted that no other archaeological evidence points to the presence of Vikings in the Ozarks.

Read More Fascinating Stories About Archaeology:

A version of this story was published in 2008; it has been updated for 2024.