It surprises no one to say that the printing press has revolutionized the world. Even the word revolution, in the sense of overturning an entire established system, comes from the 1543 publication of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus. It used the orbits of the planets, called “revolutions,” to argue for a sun-centered system over an Earth-centered one. But the people behind the books, the ones who made these objects, left their own marks too.

With my co-author JP Romney, I’ve written an entire book about the flesh-and-blood humans behind the printed book called . There’s more to that physical object we see most of the time only as a stand-in for the ideas it holds. Evidence of this lives even in our language: The following everyday phrases all came from the practical lives of people at work behind the scenes, printing books that would carry revolutionary ideas to the front lines.

1. OUT OF SORTS

This phrase has come to mean feeling a bit off, unwell, or grumpy—which is entirely appropriate because it comes from printers running out of type. A sort is an individually cast piece of type. For most of the history of print, purchasing type was expensive, and to save on costs, many printers would only keep enough on hand to get the job done. But sometimes this meant running out of type in the middle of a job, making you out of sorts.

2. MIND YOUR P’S AND Q’S

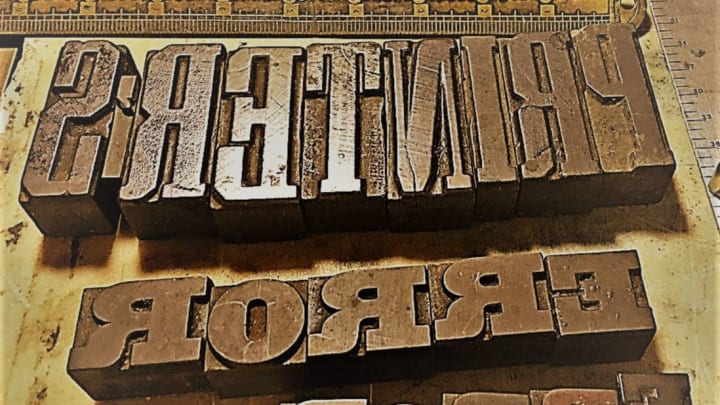

This phrase means being on one’s best behavior in British English, and paying close attention in American English. Both versions make sense coming from the print shop. Setting type means placing each individual letter in backward, so that when the inked type is pressed into paper, the mirror image reads the right way forward.

This required a certain amount of focus from the workers who set the type (known as “compositors”), especially when it came to letters that look like mirror images of each other. In older type cases, each letter was kept in a segregated section to be picked out by the compositor setting the type. The lowercase p’s and q’s are right next to each other, just begging to be mixed up. That’s why it’s “mind your p’s and q’s,” not “mind your b’s and d’s,” which are not neighbors in the type case.

3. AND 4. UPPERCASE AND LOWERCASE

The type case clearly ruled the compositors’ lives. But more than that, it changed the way we think about the alphabet. Look back at that image of the type case from Moxon’s book published in 1683. The case is tilted up slightly. All the capital letters are on the top, or the uppercase. The ones in the lower part of the case are, you guessed it, all lowercase.

5. HOT OFF THE PRESS

You can be forgiven for assuming that “hot” in “hot off the press” means the most up-to-date news. You’re right, but for the wrong reason. The paper coming off the press wasn’t literally hot, nor did the press itself heat up. It came from the “hot” type cast on the Linotype machine (above). Invented by the German-born American immigrant Ottmar Mergenthaler, this machine allowed compositors to type on a keyboard what they wanted to print. As they went along, the machine would cast the type right there out of molten metal (mostly lead). Considering how time-consuming and expensive it was to have a lot of “cold” (previously cast) type around to set by hand, this was a major innovation. The machine got its name from the delighted reaction of the owner of the New York Tribune: “You have done it, you have produced a line o’ type.”

6. STEREOTYPE

In yet another example of font tyranny, the process of stereotyping sought to address the chronic scarcity of type supplies by making molds of already set type, then casting whole metal plates of the page for reprinting later. That way you could take apart the type (called “distributing”) and immediately use it for other projects. Stereotyping was expensive, but imagine that poor compositor having to re-set some ridiculously popular book for the 26th time. A book had to reach a certain level of demand to merit the high expense of stereotyping, but it was worth it.

Take the idea of creating thousands of exact printed copies from a single original setting of type just one step further and you get the modern meaning: assuming that every person from a single group is the exact same.

7. CLICHÉ

Here is another printing innovation that snuck into our everyday speech with a simple step from the literal to the figurative. Cliché is the French word for stereotyping. But instead of casting whole plates from metal, the French would cast frequently used phrases in one block, ready to be set among the individual letters to save time. These were phrases used so much they became cliché. The French verb clicher means “to click,” which imitated the sound made when striking metal to create stereotype plates.

8. TYPECASTING

When an actor is chosen for a role because she fits a certain profile, she has been typecast. “Type” and “cast”: those are two words you’ve seen a few times in this list. In one of the common processes for shaping metal such as type, you create a mold into which molten metal is poured. It then cools and hardens into the shape defined by the mold. This process is called casting, and the word typecast is believed to be a nod to it. The same metal shaping method is also where “to fit a mold” comes from.

9. MAKE AN IMPRESSION

While this figure of speech is a metaphor for doing something that makes you memorable, it’s all tied up in a word for “printing.” The Latin word imprimere means “to press into or upon.” In British English, rare book dealers tend to refer to a print run as an “impression” (whereas American dealers call it a “printing”). It also survives on a slightly different track in our word imprint. Whether you’re dressed to impress, making a good impression, or impressive in your bow staff skills, you’re borrowing a term that made it into English thanks to the printing press.

10. DITTO

This word, used as a shorthand to repeat something that’s already been said, ultimately comes from the Italian word detto, the past participle of “to say.” But the word gained steam in the early 20th century with a duplicating machine produced by DITTO, Inc. The company’s logo? A single set of quotation marks, which we use to mean “ditto.”

Learn more about how laziness, feuds, and madness changed the world through print in our book .