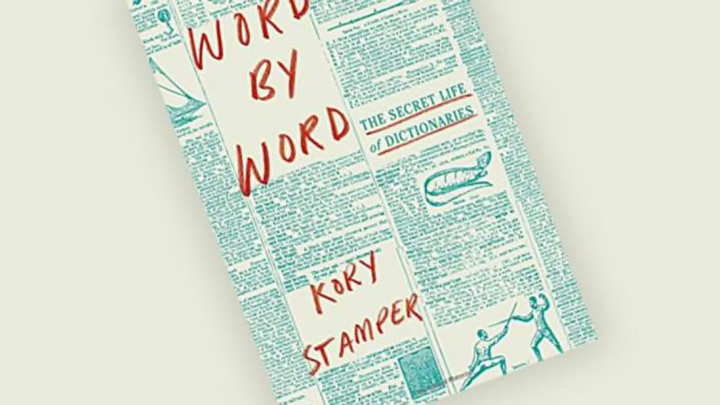

The dictionary is such a comforting, authoritative presence in our culture that it sometimes feels as if it’s always existed. But a dictionary must be made. How does a dictionary come to be? The answer is also the title to a new book by Merriam-Webster editor Kory Stamper: Word by Word.

Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries is a captivating inside look at the job of dictionary making from both a personal and historical angle. Stamper begins with the interview that landed her an entry-level position at America’s oldest dictionary maker and takes the reader along as she learns the ropes and works her way up, the process sometimes turning her original love of words on its head in ways she didn’t expect. Here are five behind-the-scenes secrets she shares about how the dictionary is made.

1. DICTIONARY WRITERS NEVER START WITH THE LETTER 'A.'

Dictionary entries require a million editorial decisions to be made about everything from font size and part-of-speech abbreviations to how to structure a definition. It can take a while to get comfortable in a set of guidelines, so it’s better start with H or one of the other letters toward the middle of the alphabet that doesn’t have as many words attached to it. If you work to the end from the middle, then tackle the beginning of the alphabet last, those letters will be “as close to stylistic perfection as possible,” Stamper writes, and it’s good to have the cleanest copy up front because “back in the days of yore when dictionaries were actually reviewed, reviewers would inevitably start looking at definitions in the first chunk of the book.”

2. THE HARDEST WORDS ARE THE LITTLE ONES.

While people tend to go to the dictionary to look up long, technical, or academic words, those aren’t particularly difficult for the definers. It’s the little words, “the ones that no one ever notices,” according to Stamper, that are the hardest to sort out. What do but, like, and as mean? What parts of speech are they? These are the questions that chain lexicographers to their desks in mental agony. Once you read about the exhausting whole month Stamper toiled on one little word—take—you will never take the little words for granted again.

3. WORKING ON A DICTIONARY WILL CHANGE THE WAY YOU SEE CEREAL BOXES.

It will also change the way you see matchbooks, shampoo bottles, barf bags—anything with text on it. Dictionaries must keep up with the language, and lexicographers are trained to notice not just new words, but emerging new uses of old words. They don't just sit around looking through great literature and scientific journals; every piece of text in the culture is another bit of evidence to consider. What sort of uses are quick and cook in the phrase “quick cook steel cut oats”? Evolving new uses? A good lexicographer cannot resist the impulse to clip out and file away the relevant piece of the oatmeal canister on which the phrase appears for future reference.

4. WHAT A GOOD DICTIONARY EDITOR MOST NEEDS IS BEST CAPTURED BY A GERMAN WORD: SPRACHGEFÜHL.

While anyone setting out to be a dictionary editor would benefit from having a firm grounding in grammar and etymology, it's not a requirement: Editors come from many backgrounds and fields not necessarily related to the study of language. What is a requirement is a quality so elusive yet specific that we had to borrow a German word for it. Sprachgefühl is a “feeling for language” or, Stamper writes,

"the odd buzzing in your brain that tells you that ‘planting the lettuce’ and ‘planting misinformation’ are different uses of ‘plant,’ the eye twitch that tells you that ‘plans to demo the store’ refers not to a friendly instructional stroll on how to shop but to a little exuberance with a sledgehammer. Not everyone has sprachgefühl, and you don’t know if you are possessed of it until you are knee-deep in the swamp of it."

Sprachgefühl can abandon even the best editors at times, putting them in an odd, confused state of “verbal fatigue” where they are driven to take a break and go searching for another human to confirm that they do, indeed, speak English.

5. IT’S ALSO GOOD TO HAVE A SOMEWHAT DIRTY, IMMATURE MIND.

A dictionary entry doesn’t just include a concise definition and information about pronunciation and grammar, it also gives example sentences that show how the word is typically used. Finding just the right sentence is an art, and much more difficult than you might think. In addition to finding the best, most straightforwardly boring illustration of a particular meaning, you must also be able to access your inner 12-year-old in order to detect any hint of double entendre. Examples like “I think we should do it!” or “That’s a big one” must be purged; to know that, you must view them through your naughtiest filter. Mistakes do happen sometimes. An example sentence at “cut” in the Merriam-Webster middle-school dictionary reads “Cheese cuts easily.” Stamper looks on the bright side: “I hope that it has given much joy to countless fart-obsessed middle schoolers and perhaps even convinced them that dictionaries are, if not cool, at least not boring and stupid.”

Find out more about the very cool, very not boring inside world of dictionary making in Word by Word.