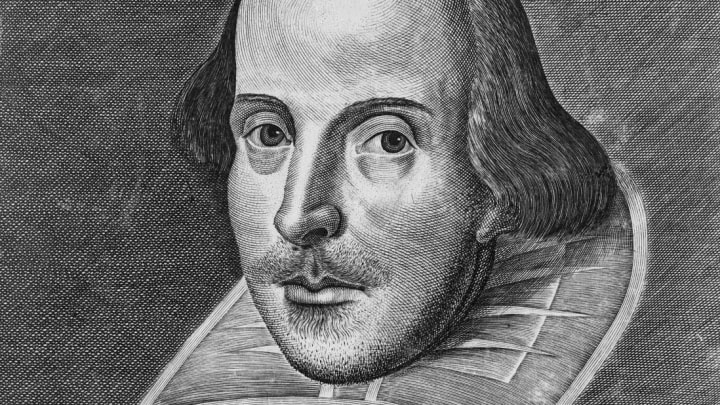

When you think of Shakespeare, you probably have a particular image of the Bard in mind: a receding hairline, heavy-lidded eyes, a thin mustache, and long, wavy hair. As historical figures go, you'd probably be able to pick him out of a lineup.

The picture you have in your head is almost certainly based on just one source: the Droeshout portrait, a black and white engraving that was the frontispiece of the First Folio (and can be seen above). Believed to have been produced by Flemish engraver Martin Droeshout in 1623, it was originally published seven years after Shakespeare's death in the first original collection of his plays. It's unlikely that Droeshout produced it from life, and most historians believe it was copied off an authentic portrait made during Shakespeare's lifetime that has not survived.

In fact, no existing portrait shows conclusively what Shakespeare looked like in real life. Since the mid-17th century, scholars have thought that the figure in the below Chandos Portrait, painted in 1610, was Shakespeare. While the painting's provenance and painting style point to its origin in Shakespeare's time, there is no definitive proof of the sitter's identity, according to Tarnya Cooper, author of Searching for Shakespeare and curatorial director of London's National Portrait Gallery.

Then there's the Cobbe portrait (below). Once owned by 18th-century Anglican Archbishop Charles Cobbe, it allegedly came to his family through the great-granddaughter of one of Shakespeare's patrons, the Earl of Southampton. Modern testing of the painting shows that it was made after 1595; the fashions depicted suggest it could have been painted as late as 1610. The unknown artist could have captured Shakespeare in life, between the ages of 31 and 46, although the figure appears somewhat younger than middle-aged.

Cobbe descendants have argued that the work is the only existing life portrait of the Bard, but art historian Sir Roy Strong described that as "codswallop" (translation: nonsense).

In fact, some historians have suggested that the Cobbe portrait is actually Sir Thomas Overbury, a poet born in 1581. Verified images of Overbury closely resemble the Cobbe figure, and—perhaps most damningly—the painting doesn't match the best existing image of Shakespeare from the same period, which was actually a bust.

The "holy trinity bust" wasn't made during Shakespeare's lifetime—it was commissioned four years after his death so that it could be placed above his grave in Stratford-upon-Avon's Holy Trinity Church. The sculpture depicts a portlier version of Shakespeare than the one we're familiar with, presumably because it shows him in his later life, and it doesn't look much like the Droeshout engraving, the Chandos portrait, or the Cobbe portrait—which are broadly similar. But because it was commissioned while his widow and son-in-law were still alive, scholars believe it's a credible likeness of the playwright.

More than 400 years after his death, Shakespeare's true identity still stirs debate. For the time being, a few secondhand images are the best clues we have to what he looked like. Luckily, his written work survives in far fuller fashion.