In 1990, for the first time ever, art went on trial.

It began in 1989 when artist Andres Serrano caught the ire of then-senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina, with his artwork called “Piss Christ,” an image of a crucifix submerged in, well, you get the idea. The senator felt the piece of “art” was obscene. Soon after the Serrano debacle, acclaimed New York City photographer Robert Mapplethorpe found himself in the crosshairs of what would become a national debate far worse than “Piss Christ.”

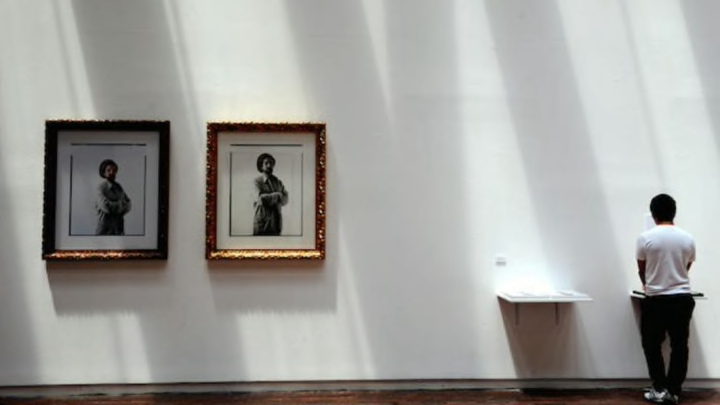

Mapplethorpe’s retrospective photography show, “The Perfect Moment,” ran in Philadelphia from December 9, 1988 to January 29, 1989 (it was organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania), and traveled to Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art; both shows went smoothly. But when the exhibit was supposed to show at Washington D.C.’s Corcoran Gallery of Art in July 1989, Helms used Mapplethorpe’s risqué black and white photographs of nude men and women in sometimes compromising situations as a means to spark a debate about public funding of the arts. To him, the photographs were flagrantly pornographic and not artful.

Helms didn’t like that the government-sponsored National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) had granted the ICA $30,000 to help fund the exhibit (the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, the City of Philadelphia, and private donors also contributed), and Helms sent a letter to the NEA, signed by 36 senators, expressing their outrage over the exhibition. “The exhibit represented a greater tug and pull of liberal and conservative values of early 1990s America,” The Cincinnati Enquirer wrote in 2000. (Also in 1990, rap group 2 Live Crew went on trial for their album As Nasty As They Want to Be, which was found to be obscene—the first time a U.S. court labeled an album as such.)

Buckling under the pressure from Helms and conservative religious organization American Family Association, the Corcoran canceled the exhibit, which caused a brouhaha of national proportions. Should taxpayer dollars be used to fund the arts? Where’s the line between obscenity and art?

Mapplethorpe didn’t live to see his art come under the microscope, as he died of complications related to HIV/AIDS on March 9, 1989. He was a gay man whose photographs encapsulated homosexuals, and in the late ’80s/early ’90s, that was much more divisive subject matter. The photos were hard to look at, but they weren’t insipid like Playboy centerfolds. “The Perfect Moment” contained three portfolios: X, Y, Z. The first one focused on homosexual sadomasochism; Y was filled with pictures of provocative flowers; and Z featured nude portraits of African American men.

In April of 1990, the exhibit was scheduled to show in Cincinnati, Ohio, a city so conservative that it was often referred to as “the most anti-gay city in America.” Citizens for Community Values demanded Cincinnatians not attend the exhibit, but when the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) unveiled “The Perfect Moment” on April 7, all hell broke loose.

At the time, Dennis Barrie was the director of the museum. During a preview night on April 6, more than 4000 museum members showed up to see the photos. “I thought we dodged a bullet,” Barrie told Smithsonian Magazine in 2015 about the preview night. “But it was the next day, when we technically opened to the public, that the vice squad decided to come in.”

The Cincinnati Enquirer detailed the snowball effect of April 7:

“At 9 in the morning, the doors opened and the grand jurors were amongst the first to come through. By 2:30 that afternoon, the grand jury announced the indictments. At 2:50, the Cincinnati Police arrived with a search warrant and cleared out the patrons.”

Hamilton County Sheriff Simon Leis was on the scene and immediately declared the photos to be “smut." “This was beyond pornography,” Leis told the Enquirer in March 2015. “When you put a fist up a person’s rectum, what do you call that? That is not art.”

There were four criminal indictments: two against the museum and two against Barrie for “pandering obscenity and illegal use of a minor in nudity oriented materials.” Seven photos, in particular, incited the indictments: five photos of men performing various acts of BDSM, and two photos involving naked children. Never before had a museum and its director been criminally charged for obscenity because of a public art exhibition.

The fallout was fast and furious. Protestors lined the streets outside of the museum, both in support of the artwork and in support of the city’s decision to put Barrie on trial. The exhibit didn’t close, but the museum only allowed patrons aged 18 and older in and placed Portfolio X behind a curtain. But the controversy also generated more interest in the show and Mapplethorpe’s work; an estimated 80,000 people came to see the photos.

Almost six months later, on September 24, 1990, the trial began. Defense attorney H. Louis Sirkin helped pick the eight jurors—four women and four men—to decide the fate of the museum and art itself. His tactic was, “You don’t have to like it, you don’t have to come to the museum,” he told Smithsonian. Judge F. David J. Albanese wouldn’t allow all 175 photos in as evidence; the jury only saw the seven photos in question. He told the jury to use a three-prong test of obscenity (Miller vs. California) in looking at the photos, including, “The appeal to the prurient interest must be the main and principal appeal of the picture.” A lot was at stake besides whether the jurors thought Mapplethorpe’s works were obscene or not: If found guilty, the museum would have to pay $10,000 in fines and Barrie would spend a year in a jail.

On October 5, 1990, the jury made its landmark decision: Not guilty. Barrie and the CAC were acquitted of all charges, and on that day, art prevailed.

“I’m absolutely convinced that if we lost that case in Cincinnati, the NEA would have been gone,” Sirkin told The Washington Post in 2015. “This is a great day for this city, a great day for America,” Barrie told the Enquirer. “[The jurors] knew what freedom was all about … I’m glad the system does work.” In 2000, James Woods played Barrie in a Golden Globe-winning Showtime movie called Dirty Pictures, about the Mapplethorpe exhibition.

For the 25th anniversary of “The Perfect Moment,” the CAC hosted a two-day symposium in 2015, featuring panels with Barrie and current museum director Raphaela Platow. Last year, CAC revisited some of Mapplethorpe’s work with “After the Moment: Revisiting Robert Mapplethorpe” and earlier this year, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles hosted “Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium.”

“The Perfect Moment” set a powerful precedent: No museum has been put on trial since.