Emily Dickinson lived nearly her entire life in Amherst, Massachusetts. She wrote hundreds of poems and letters exploring themes of death, faith, emotions, and truth. As she got older, she became reclusive and eccentric, and parts of her life are still mysteries. Here are 11 things you might not know about Dickinson’s life and work.

BORN | DIED | SELECTED WORKS |

|---|---|---|

December 10, 1830, Amherst, Massachusetts | May 15, 1886, Amherst, Massachusetts | “Because I could not stop for Death,” “Hope is the thing with feathers,” “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” |

1. Emily Dickinson wasn’t a fan of traditional punctuation.

Dickinson’s approach to poetry was unconventional. As her original manuscripts reveal, she interspersed her writing with many dashes of varying lengths and orientations (horizontal and vertical), but early editors cleaned up her unconventional markings, publishing her poems without her original notations. Scholars still debate how Dickinson’s unusual punctuation affected the rhythm and deeper meaning of her poems. If you’re interested in seeing images of her original manuscripts, dashes and all, head to the Emily Dickinson Archive.

2. Dickinson was a rebel.

Besides punctuation, Dickinson rebelled in matters of religion and social propriety. Although she attended church regularly until her thirties, she called herself a pagan and wrote about the merits of science over religion. Dickinson neither married nor had children, and she largely eschewed in-person social interactions, preferring to communicate with most of her friends via letters.

3. Dickinson never published anything under her own name.

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Dickinson’s friend and mentor, praised her writing ability and innovation but discouraged her from publishing her poems, probably because he thought that the general public wouldn’t be able to recognize (or understand) her genius. Between 1850 and 1878, 10 of Dickinson’s poems and one letter were published in newspapers and journals, but she didn’t give permission for any of these works to be published, and they weren’t attributed to her by name. Although Dickinson may have tried to get some of her work published—in 1883, for example, she sent four poems to Thomas Niles, who edited Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women—she instead let her closest friends read her poems, and compiled them in dozens of homemade booklets. The first volume of Dickinson’s poetry was published in 1890, four years after her death.

4. She had vision problems in her thirties.

In 1863, Dickinson began having trouble with her eyes. Bright light hurt her, and her eyes ached when she tried to read and write. The next year, she visited Dr. Henry Willard Williams, a respected ophthalmologist in Boston. Although we don’t know what Williams’s diagnosis was, historians have speculated that she had iritis, an inflammation of the eye. During her treatment, the poet had to eschew reading, write with just a pencil, and stay in dim light. By 1865, her eye symptoms went away.

5. Dickinson lived near family for her entire life.

Although Dickinson spent most of her adult life isolated from the world, she maintained close relationships with her brother and sister. Her brother, Austin, with his wife and three children, lived next door to her in a property called The Evergreens. Dickinson was close friends with Austin’s wife, Susan, regularly exchanging letters with her sister-in-law. And Dickinson’s own sister, Lavinia, also unmarried, lived with her at the Dickinsons’ family home.

6. The identity of the man Dickinson loved is a mystery.

Dickinson never married, but her love life wasn’t completely uneventful. In the three “Master Letters,” written between 1858 and 1862, Dickinson addresses “Master,” a mystery man with whom she was passionately in love. Scholars have suggested that Master may have been Dickinson’s mentor, a newspaper editor, a reverend, an Amherst student, God, or even a fictional muse. Nearly two decades later, Dickinson started a relationship with Judge Otis Lord, a widowed friend of her father’s. Lord proposed to the poet in 1883, didn’t get an answer, and died in 1884.

7. Dickinson may have suffered from severe anxiety.

Historians aren’t sure why Dickinson largely withdrew from the world as a young adult. Theories for her reclusive nature include that she had extreme anxiety, epilepsy, or simply wanted to focus on her poetry. Dickinson’s mother had an episode of severe depression in 1855, and Dickinson wrote in an 1862 letter that she herself experienced “a terror” about which she couldn’t tell anyone. Mysterious indeed.

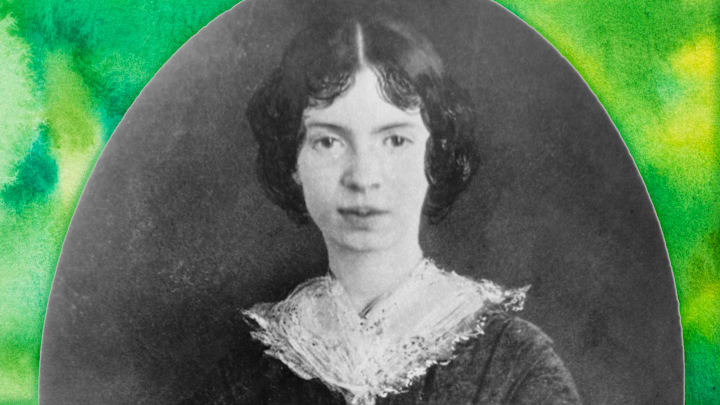

8. It’s a myth that Dickinson only wore white.

Due to her reclusive nature, legends and myth about Dickinson’s personality and eccentricities spread. Before her death, Dickinson often wore a white dress and told her family that she wanted a white coffin and wished to be dressed in a white robe. But the widespread rumor that she only wore white was false. In a letter, she made a reference to owning a brown dress, and photos of her show her wearing dark clothing. For several decades, the Amherst Historical Society and Emily Dickinson Museum have displayed the poet’s well-known white dress (as well as a replica).

9. Her brother’s mistress edited and published her poetry.

In 1883, Dickinson’s brother Austin started an affair with a writer named Mabel Loomis Todd. Todd and Emily Dickinson exchanged letters but never met in person. After Dickinson’s death, the poet’s younger sister, Lavinia, asked Todd to help arrange Dickinson’s poems to be published. So Todd teamed up with Thomas Higginson to edit and publish Dickinson’s work, creating an awkward family dynamic between Dickinson’s brother, sister, and sister-in-law. After publishing the first volume in 1890, Todd and Higginson published a second collection of Dickinson’s poetry the next year. Todd even wrote articles and gave lectures about the poems, and she went on to edit Dickinson’s letters and a third volume of her poems.

10. Dickinson had a big green thumb.

Throughout her life, Dickinson was a major gardener. On her family’s property, she grew hundreds of flowers, planted vegetables, and cared for apple, cherry, and pear trees. She also oversaw the family’s greenhouse, which contained jasmine, gardenias, carnations, and ferns, and she often referred to plants in her poetry. Recently, the Emily Dickinson Museum, located on the Dickinsons’ former property, led a restoration of Dickinson’s garden and greenhouse. Archaeologists restored and replanted apple and pear trees on the property, and they’re hoping to find seeds from the 1800s to use for future planting.

11. Dickinson’s niece added “called back” to her tombstone.

On May 15, 1886, Dickinson died at her home in Amherst of kidney disease or, as recent scholars have suggested, severe high blood pressure. Her first tombstone in Amherst’s West Cemetery only displayed her initials, E.E.D. (for Emily Elizabeth Dickinson). But her niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, later gave her deceased aunt a new headstone, engraved with the poet’s name, birth and death dates, and the words “Called Back,” a reference to an 1880 novel of the same name by Hugh Conway that Dickinson enjoyed reading. In the last letter that Dickinson wrote (to her cousins) before she died, she only wrote “Called Back.”

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2023.