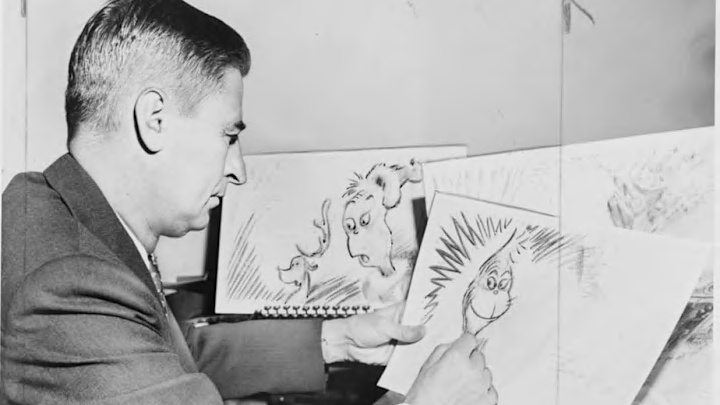

Theodor Seuss Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss, wasn't actually a doctor (at least not until his alma mater, Dartmouth, gave him an honorary degree), but his unique poetic meter and leap-off-the-page illustrations made him one of the most successful children's writers in history. Here's a little background on some of his greatest hits.

1. The Lorax

The Lorax is widely recognized as Dr. Seuss's take on environmentalism and how humans are destroying nature. (The character may have been inspired by a real-life monkey.) Groups within the logging industry weren't very happy about it and later sponsored Truax—a similar book, but from the logging point of view. Another interesting fact: The Lorax used to contain the line, "I hear things are just as bad up in Lake Erie," but 14 years after the book was published, students at the Ohio Sea Grant Education Program wrote to Seuss and told him how much the conditions had improved and implored him to take the line out. Dr. Seuss agreed and said that it wouldn't be in future editions.

2. The Cat in the Hat

Dr. Seuss wrote The Cat in the Hat because he thought the famous Dick and Jane primers were boring. Because kids weren't interested in the material, they weren't exactly compelled to use it repeatedly in their efforts to learn to read. So, The Cat in the Hat was born. As Donald E. Pease writes in his biography of the author, Seuss "analyzed the reading process, particularly the part that pertained to a child's ability to correlate words with images and sounds that made them legible" before he started writing.

3. Green Eggs and Ham

Bennett Cerf, Dr. Seuss's editor, bet him that he couldn't write a book using 50 words or less. The Cat in the Hat was pretty simple, after all, and it used 225 words. Not one to back down from a challenge, Geisel started writing and came up with Green Eggs and Ham—which uses exactly 50 words.

The 50 words, by the way, are: a, am, and, anywhere, are, be, boat, box, car, could, dark, do, eat, eggs, fox, goat, good, green, ham, here, house, I, if, in, let, like, may, me, mouse, not, on, or, rain, Sam, say, see, so, thank, that, the, them, there, they, train, tree, try, will, with, would, you.

4. Horton Hears a Who!

The line from the book "A person's a person, no matter how small" has been used as a slogan for pro-life organizations for years. It's often questioned whether that was Seuss's intent in the first place, but when he was still alive, he threatened to sue a pro-life group unless they removed his words from their letterhead. Karl ZoBell, the attorney for Dr. Seuss's interests, said in 2008 that the author's widow, Audrey (who passed away in 2018) didn't like people to "hijack Dr. Seuss characters or material to front their own points of view."

At any rate, Seuss himself once said in an interview he came up with the idea during his time in Japan reporting for a LIFE magazine article. "Japan was just emerging, the people were voting for the first time, running their own lives—and the theme was obvious: 'A person’s a person no matter how small,' though I don’t know how I ended up using elephants," he said.

5. Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now!

It's often alleged that Marvin K. Mooney Will You Please Go Now! was written specifically about Richard Nixon, but the book came out only two months after the whole Watergate scandal. Which makes it unlikely that the book could have been conceived of, written, edited, and mass-produced in such a short time; also, Seuss never admitted that the story was originally about Nixon.

But that's not to say he didn't understand how well the two flowed together. In 1974, he sent a copy of Marvin K. Mooney to his friend, Art Buchwald, at The Washington Post. In it, he crossed out "Marvin K. Mooney" and replaced it with "Richard M. Nixon," which Buchwald reprinted in its entirety.

6. Yertle the Turtle

Yertle the Turtle = Hitler? Yep. If you haven't read the story, here's a little overview: Yertle is the king of the pond, but he wants more. He demands that other turtles stack themselves up so he can sit on top of them to survey the land. Mack, the turtle at the bottom, is exhausted. He asks Yertle for a rest; Yertle ignores him and demands more turtles for a better view. Eventually, Yertle notices the moon and is furious that anything dare be higher than himself, and is about ready to call for more turtles when Mack burps. This sudden movement topples the whole stack, sends Yertle flying into the mud, and frees the rest of the turtles from their stacking duty.

Dr. Seuss actually said Yertle was a representation of Hitler. Despite the political nature of the book, none of that was disputed at Random House—what was disputed was Mack's burp. No one had ever let a burp loose in a children's book before, so it was a little dicey. In the end, obviously, Mack burped. As Seuss recalled, "I used the word burp, and nobody had ever burped before in the pages of a children's book. It took a decision from the president of the publishing house before my vulgar turtle was permitted to do so."

7. The Butter Battle Book

When Dr. Seuss wrote 1984'sThe Butter Battle Book, "the entire world was on edge about the possibility of nuclear annihilation," writes Brian Jay Jones in Becoming Dr. Seuss, "which was exactly the reason Geisel wanted to say something about it."

The Yooks and Zooks are societies who do everything differently. The Yooks eat their bread butter-side up and the Zooks eat their bread butter-side down. Obviously, one of them must be wrong, so they start building weapons to outdo each other: the "Tough-Tufted Prickly Snick-Berry Switch," the "Triple-Sling Jigger," the "Jigger-Rock Snatchem," the "Kick-A-Poo Kid," the "Eight-Nozzled Elephant-Toted Boom Blitz," the "Utterly Sputter," and the "Bitsy Big-Boy Boomeroo."

The book concludes with each side ready to drop their ultimate bombs on each other, but the reader doesn't know how it actually turns out. The anti-war book was pulled from the shelves of some libraries for a while because of the reference to the Cold War and the arms race.

8. And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street

Dr. Seuss's first children's book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, was rejected 27 times, according to Guy McLain of the Springfield Museum in Geisel's hometown. Only after Seuss ran into a friend who'd just been hired by a publishing house did the book get the green light. "He said if he had been walking down the other side of the street," McLain told NPR, "he probably would never have become a children's author."

9. Oh, the Places You'll Go!

Oh, The Places You'll Go!, published in 1990, was the final book released during the author's lifetime. It was an instant success, even topping the New York Times bestseller list for adult fiction—a fact that led Seuss to say, "This proves it! I no longer write for children, I write for people!"

10. How the Grinch Stole Christmas!

Dr. Seuss’s iconic Grinch debuted in the pages of Redbook magazine in his 1955 poem "The Hoobub and the Grinch." Seuss—who, according to Jones, had complicated feelings about the commercialism of Christmas—brought the character back for 1957’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas! “I did this nasty, anti-Christmas character that was really me,” Seuss would later say.

Seuss’s story was later turned into the famous 1966 cartoon special. In the Dr. Seuss-sanctioned cartoon, Frankenstein's Monster himself, Boris Karloff, provided the voice of the Grinch and the narration. Tony the Tiger, a.k.a. Thurl Ravenscroft, is the voice behind the song "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch." Though Ravenscroft received no credit on screen, his name did appear in newspaper mentions of the special.

A version of this story ran in 2009; it has been updated for 2022.