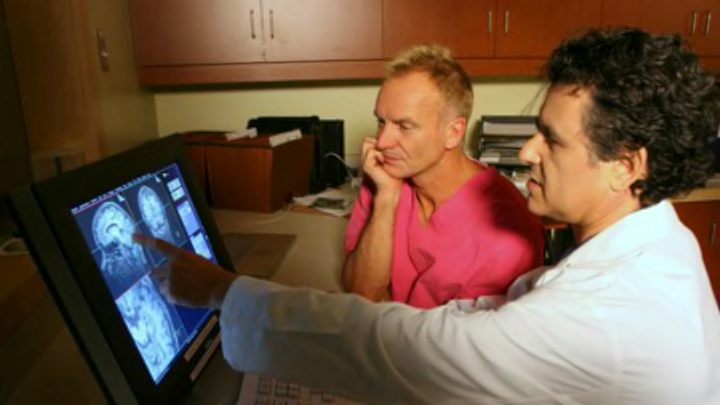

You never know what you’re going to find when you rummage around inside somebody’s brain. Scientists had the opportunity to do just that with a very special test subject: Sting. Yes, Sting, as in Sting, the former Police front man, human rights activist, and world-renowned sometimes-eccentric. The researchers described the results of their studies in the journal Neurocase.

About a decade ago, cognitive psychologist Daniel Levitin began hearing from musicians who had read and loved his book This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. So Levitin was pleased, but not hugely surprised, when he got a call from Sting’s people. The musician would be passing through Montreal on a tour, they said, and was wondering if he could tour Levitin’s lab. Absolutely, Levitin said. And then he asked if he could scan Sting’s brain. The game musician said yes.

In preparation for the superstar’s visit, Levitin devised a series of three musical experiments, all of which would be conducted while Sting was in the scanner. The first experiment aimed to discern how, and if, composing music was different from writing poetry or creating art. The second explored the differences (or similarities) between imagining and actually listening to music, and the third would track brain activity as Sting listened to a variety of music in genres from classical to reggae.

The day of the study, Sting showed up, ready to work. But before Levitin and his team could even get the singer into the scanner, the power blew across the entire campus. The test subject was determined, though; he waited out the outage, even skipping his sound check so the experiments could proceed. After the scans, he packed up and headed out to perform.

To analyze the experimental results, Levitin teamed up with brain scan expert Scott Grafton of the University of California at Santa Barbara. Considering the aims of the study, Grafton decided to use two new techniques—multivoxel pattern analysis and representational dissimilarity analysis—both of which look for similarities in brain activity.

As Levitin expected, Sting’s brain suggested that the act of composing music is indeed different from other creative processes, and that thinking about music and listening to it activate the same regions in the brain. But there were some surprises, too, Levitin said in a press statement: “Sting’s brain scan pointed us to several connections between pieces of music that I know well but had never seen as related before,” he said.

Without conscious thought, the composer’s brain had noticed similarities between works like Piazzolla’s “Libertango” and the Beatles song “Girl,” both of which are in minor keys and rely on similar melodic motifs. The brain scans showed another link between Sting’s own song “Moon Over Bourbon Street” and Booker T. and the MG’s “Green Onions.” Both are swing songs in F minor with a tempo of 132 beats per minute, but to even a conscious listener they might not necessarily sound similar.

“These state-of the-art techniques really allowed us to make maps of how Sting’s brain organizes music,” Levitin says. “That’s important because at the heart of great musicianship is the ability to manipulate in one’s mind rich representations of the desired soundscape.”

The researchers note that what’s true of Sting is not necessarily true of everyone else, or even other musicians. But, they say, the techniques used in these experiments have broad potential to study “… all sorts of things: how athletes organize their thoughts about body movements; how writers organize their thoughts about characters; how painters think about color, form and space.”

Know of something you think we should cover? Email us at tips@mentalfloss.com.