Humanity's adventure with the comet lander Philae has ended. Earlier this week, the European Space Agency switched off radio communications with the plucky spacecraft, whose landing on the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on November 12, 2014 captivated the world. The decision was made so that Philae's companion and communications relay, Rosetta, might conserve every bit of its energy for its own payload of scientific instruments. Philae had long stopped transmitting from the comet's surface, and ESA maintained little hope that communication would be restored before the conclusion of the mission in September.

ROCKY LANDING

Philae's landing capped off an otherwise grim year in news, pushing briefly from the front pages headlines of beheadings and invasion, and reminding many that we are capable of so much more. And yet it didn't go exactly as planned. The mission as designed would have set Philae down on comet 67P in a controlled fashion, with thrusters slowing its descent and ice screws in each of its three legs stabbing into the surface on touchdown. Harpoons, meanwhile, would fire and secure the spacecraft to the comet for the duration of the mission.

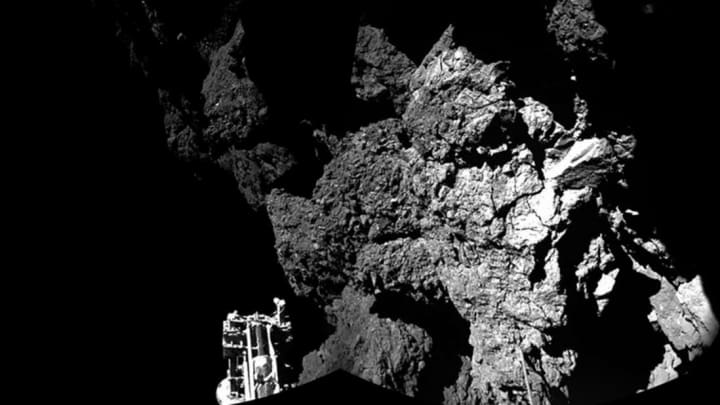

That's not what happened. Instead, both the thrusters and harpoons failed to activate, leaving Philae to bounce around on 67P. Astonishingly, the spacecraft survived all of this, finally coming to rest in a shadowy area and at an angle, where it set about doing science. The shadow—presumably from a cliff face—proved troublesome for the spacecraft; its secondary battery relied on solar power to recharge. Nevertheless, before Philae fell silent, it returned the vast majority of its intended science.

Philae descends to the surface of comet 67P. Image credit: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA

Seven months later, in June 2015, the mission operations center back on Earth received a startling but welcome message from Rosetta, still in orbit around the comet: Philae was alive, its batteries recharged and systems restarted. Though communications proved challenging, scientists successfully activated an instrument designed to study the comet's interior. Whether from mechanical problems or from the comet's instability as it neared the Sun, however, Philae again went silent. Its last transmission came about a year ago, on July 9, 2015.

WHAT PHILAE FOUND

Philae's short but eventful life produced a bonanza of data. Comet 67P has no magnetic field, and bears less ice than was expected. The comet's surface was much rougher than scientists anticipated, and its subsurface proved even more surprising. Before the landing, scientists expected the subsurface of comets to be like that of compacted snow. Some feared, in fact, that upon landing, Philae would be swallowed up by several feet of dust that might rest on the comet's exterior. Instead, the spacecraft revealed that beneath a few inches of dust is a very hard crust. Further down, the comet is also extremely porous, with three-quarters of it comprised of empty space.

A central question vexing scientists involves the origin of comets. Are they the remains left behind during the early formation of the solar system? Or are they younger—fragments produced by collisions between celestial objects beyond planet Neptune? The Rosetta mission has possibly answered that question: comets are primordial, the leftovers from the solar system's birth. Moreover, because Philae discovered that 67P is rich in the sorts of organic compounds that would give rise to life on Earth, such compounds likely existed during the formation of the solar system. Comets act as celestial messengers, and it is therefore a near certainty that they have spent the last 4.5 billion years seeding the building blocks of life far and wide.

ETERNAL REST

The Rosetta spacecraft, which carried Philae to the comet, will remain in orbit around 67P for another two months. During that time, it will continue its science mission. This will end on September 30, 2016, when it will be directed to join Philae on the comet's surface. During the descent and landing, Rosetta will collect data and take high-resolution images. The mission will end because of the spacecraft's distance from both the Sun and the Earth—there will be insufficient solar power to keep it running, and too little bandwidth to transmit data in any event. The two spacecraft have earned their eternal rest on the comet. The data that they collected will keep scientists busy for the next several years, and continue to yield insights and revolutions in the scientific understanding of comets.