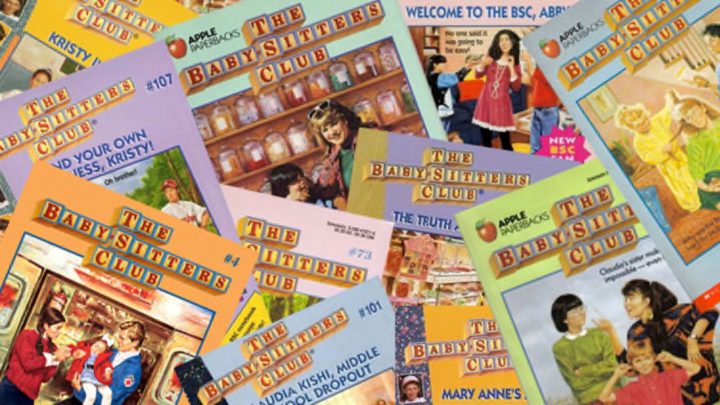

In 1986, Scholastic published the first The Baby-sitters Club book, Kristy’s Big Idea. Before long, the books were hitting bestsellers lists and what started as a four-part miniseries would eventually grow to more than 200 books. By the series' original end in 2000, 176 million copies of Baby-sitters Club books had been sold—which, if stacked on top of each other, would be as tall as 77,203 Empire State Buildings.

In 2006, The Baby-sitters Club got a graphic novel makeover (it, too, kicked off with Kristy's Big Idea). There was also an HBO series in 1990, and a film in 1995. Now, Netflix's version of the beloved book series starts streaming July 3.

Here are a few things you might not have known about the hugely popular books, which didn’t just turn kids into readers—it also turned them into babysitters when they created their own real-life clubs.

1. Scholastic editor Jean Feiwel came up with the idea and the title for The Baby-sitters Club, then hired Ann M. Martin.

When Jean Feiwel joined Scholastic in 1983, she was put in charge of the publisher’s preteen and young adult book clubs. The idea for Baby-sitters Club came when Feiwel noticed that a book called Ginny’s Babysitting Job was a top-seller month after month, despite having “a rotten cover” and being buried on the third or fourth page of the book club's catalog. “I thought, it must be something about baby-sitting because it’s not something about Ginny or the cover,” Feiwel said.

The editor then approached Ann M. Martin—whom she had briefly worked with at Scholastic before Martin left to become a freelance writer—with the idea and the series’ title. “All I gave Ann was just a glimmer of an idea—a series about a babysitters club,” Feiwel told Publisher’s Weekly in 2010. “She came up with everything else.”

2. Ann M. Martin drew from her own friendships and experiences to write The Baby-sitters Club books.

“First, I had to decide exactly what a babysitters club might be and I decided that it would be a babysitting business,” Martin told Glamour in 2010. “And then I created the four original main characters.” The author, who not long before had been a teacher for a year, said that experience was foremost in her mind: “I was also thinking of the kids in my classroom who came from really different kinds of backgrounds. I remember at the time being struck by how many came from families in which the parents were divorced or a lot of blended families. And this was just a pretty typical classroom in Connecticut.”

Princeton, New Jersey, where Martin grew up, was the inspiration for BSC’s Stoneybrook, Connecticut, and when it came time to create her characters, Martin drew on her own friendships: Mary Anne and Kristy were based on the author and her best friend Beth, respectively, when they were growing up.

“We started a number of clubs and they were all her idea,” Martin told The Washington Post in 1995. “They lasted for about two days, but it was like the old Judy Garland-Mickey Rooney movies: ‘Hey, let’s start a club.’ We’d meet in Beth’s bedroom, eat cookies, and then go home.”

Claudia, meanwhile, was named after Martin’s friend Claudia Werner. She also wrote her goddaughters into the books, who readers might remember as the Perkins girls, frequent charges of the BSC: “As adults, they tell me that it's a lot of fun for them to look back and read about the characters that were inspired by them,” Martin told Scholastic.

Martin spent a lot of time babysitting in her youth, but that wasn’t the only thing she used for inspiration: Her childhood desire to find a secret passageway in her house (which was designed and constructed by her parents just five years before they moved in) inspired The Ghost at Dawn’s House, while summer vacations on the Jersey Shore—and in Surf City, Avalon, Stone Harbor, and Cape May in particular—inspired Sea City, New Jersey, the fictional town where members of the BSC enjoyed summer adventures in Boy Crazy Stacey.

One thing Martin never used as inspiration: The thousands of ideas that were sent to her by fans, which all tended to be too dramatic for the series.

3. The Baby-sitters Club was intended to be a four-book miniseries.

The idea was that each book would focus on one of the four original characters—Kristy, Mary Anne, Claudia, and Stacey—and have a run of 30,000 copies. The first, Kristy’s Big Idea, debuted in August 1986 in bookstores and in book clubs; it quickly sold out of its initial run, then sold an additional 120,000 copies. The other books also did well—so well that Scholastic requested another two BSC novels with initial runs of 100,000 copies; starting with Mary Anne Saves the Day, the books were printed in runs of 250,000 (it would one day become the first children’s book to appear on the USA Today Bestseller List) and were soon being published at the rate of one a month.

The Baby-sitters Club was a hit, and it was no wonder it resonated with young girls: The books focused on issues and topics they would find relatable. Things like divorce, the death of a pet, sibling rivalry, disabilities, cancer, racism, eating disorders, learning disorders, the death of a friend, and sexism were all fair game. Drugs and sex were not, however. “I think these topics are a little heavy for younger readers,” Martin told TIME in 1991. (More mature issues like alcoholism and abusive relationships were explored in the Dawn-centric spin-off California Diaries.)

4. The Baby-sitters Club covers were painted by Hodges Soileau—and one featured Kirsten Dunst.

Hodges Soileau, who now teaches part-time at Ringling College of Art and Design in Sarasota, Florida, painted covers for more than 300 books in various genres, including beloved series like The Boxcar Children as well as Harlequin romance novels. For The Baby-sitters Club covers, he worked from photographs of models—one of whom was a young Kirsten Dunst on her very first job. “My first cover was a book in the Baby-sitters Club series, Claudia and the Phantom Phone Calls,” Dunst told Parade in 2008.

5. The handwritten portions of The Baby-sitters Club books were all created by one employee.

Each BSC book focuses on a different character and features handwritten passages—and though each may have looked as unique as the BSC member it belonged to, they all actually came from one hand: “The handwriting for the girls—all of them!—was done by one person in Scholastic's art department,” Martin said.

6. Originally, Martin wrote all of The Baby-sitters Club books herself.

When The Baby-sitters Club debuted, Martin was writing each of the books herself at the rate of one per month. She had a routine: Each morning she’d wake up early, then write longhand on yellow legal pads from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Soon, Scholastic added a spin-off series to her load: Baby-sitters Little Sisters, which she also had to write at the rate of one a month. And her workload continued to grow: In 1995, Martin told The Washington Post that “I’m responsible for 12 Baby-sitters Club books a year. Twelve Little Sisters books, six mysteries, and about four Ms. Coleman books [another BSC spin-off], and two or three other titles ... It totals over 30 books a year. I don’t even think Stephen King could do it.”

7. A multitude of Baby-sitters Club spin-offs eventually meant hiring ghostwriters.

When the workload became too great for Martin, she and Scholastic opted to hire ghostwriters—a small group of writers that Martin and her editors had worked with before, including Ellen Miles, Peter Lerangis, and Nola Thacker. “I almost didn’t have a choice, because there is no way I could have written all of those books myself,” Martin told CNN in 2014. “Each of the authors had to read all of the books in the series up to the point from which they would be writing so they would have the background.” (It’s easy to tell if a book has been ghostwritten: Look for an acknowledgments page that thanked the ghostwriter for “help in preparing this manuscript” or “help in writing this book.”)

But just because the books were ghostwritten doesn’t mean Martin had stepped away entirely: She outlined the plot for each book (“I am a huge outliner. I outline everything,” she told CNN) and edited them as they came in. “I really enjoyed it,” she said. “I had been an editor before I became a full-time writer, so this was like putting my editorial hat back on.”

8. There was a Baby-sitters Club bible

To keep consistency, the editorial team created a BSC “bible” full of details like each character's eye color, hobbies, and habits. The bible was overseen by David Levithan, then a 19-year-old intern who would go on to become Scholastic’s editorial director. “I was the guy on the subway not only reading BSC, I was reading it with a highlighter to keep track of who spoke French, who had green eyes, and so on,” he told The Atlantic.

The bible would go on to be published as a book of its own: The Complete Guide to the Baby-sitters Club.

9. The hardest Baby-sitters Club book for Martin to write was Claudia and the Sad Good-bye.

Claudia and the Sad Good-bye, which deals with the death of Claudia’s grandmother, was written shortly after Martin lost her own grandmother. “There was a lot of me in the book,” Martin told Life in 2002.

Claudia’s uber-fashionable outfits, incidentally, were sourced from clothing catalogs, magazines, and what kids were wearing on TV.

10. Reading about Stacey’s diabetes in The Baby-sitters Club helped some readers get diagnosed.

Martin, who gave Stacey diabetes after two of her friends were diagnosed with the condition, told Entertainment Weekly in 2012, “It never occurred to me that after I wrote this book [The Truth About Stacey] I would hear from so many readers who actually recognized the warning signs of diabetes and [got] diagnosed themselves based on Stacey’s story.”

The author’s descriptions of diabetes helped in other ways, too. As one commenter wrote on Martin’s Facebook page :

“I have to admit that a lot of what you wrote about Stacey's diabetes really helped me tremendously when I took Anatomy and Physiology recently. The descriptions you wrote about the disease were very accurate.”

11. When Stacey was written out of The Baby-sitters Club, fans freaked out.

In BCS #13, Good-bye, Stacey, Good-bye, Stacey heads back to New York City. “I thought it was reasonable that in a group of friends the size of the Baby-sitters Club, one member might move away at some point,” Martin told Entertainment Weekly. “Since Stacey hadn’t grown up in Stoneybrook, I thought it made sense that she might have to move back to New York City.”

But at that time, Stacey was BSC’s most popular character, and fans were not pleased: “BIG MISTAKE! Stacey’s huge fan base let it be known that they wanted her back in Stoneybrook asap!” Martin wrote on her Facebook page. Stacey had her homecoming in BSC #28, Welcome Back, Stacey!

12. John Green is a Baby-sitters Club fan.

Boys were BSC fans, too—including author John Green. He wrote in the September/October addition of The Horn Book Magazine that, when he was around 10, he started to hate the Hardy Boys—not the books, but the characters. “They were vapid and preppy and struck me as entirely too popular,” he wrote. “The Hardy boys were never lonely or inexplicably sad. They got scared sometimes, but only because the cave was dark. Every 10-year-old worth his or her salt knows that caves aren't nearly as terrifying as people.” But Green found what he was looking for in BSC:

“I found the Baby-sitters Club, and I was in love. I was in love with Stacey, of course, because she was awesome and cute and industrious and also vulnerable and prone to getting herself into the kind of trouble that one does not often find in caves. But I was also in love with the books. The BSC offered me characters whose conflicts were like my own, or at least relevant to my own: they experienced interpersonal conflict, and even internal conflict. If I may paraphrase Faulkner when talking about the Baby-sitters Club: for me, at least, Stacey's griefs grieved on universal bones.”

That devotion lasted into Green's college years. During a fight with a college girlfriend, Green retreated to her family’s guest room, where he found her old BSC books. “I spent an hour reading Claudia and the Sad Good-bye, and by the time I reached its end, I felt much better,” he wrote. “I was 19 years old. By then, I needed more from books than the BSC could provide—but what they could provide, I still needed.”

13. There was a Baby-sitters Club TV series on HBO.

When Scholastic wanted to create a BSC TV show, they first approached the networks, where the publisher hit an unexpected roadblock: No one thought a TV show aimed at girls would be successful. One network suggested making the show a cartoon, and others discussed adding more boy characters before giving the go-ahead, but Scholastic dismissed those options. Instead, the publisher created two straight-to-VHS specials themselves.

Finding young actors that matched the characters in the books was no easy task. “We saw 500 girls because we were looking for very specific physical characteristics,” Deborah Forte, then VP at Scholastic, told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1992. “And they had to act, too.”

The videos were a surprise success: 1 million cassettes were sold for $12.95 each and based on that, HBO picked up the series: Thirteen half-hour episodes ran throughout 1991. The episodes later aired on the Disney Channel, and you can watch them today on Hulu.

14. There was also a Baby-sitters Club movie.

Just a few years later, Columbia Pictures released The Baby-sitters Club movie, which starred Schuyler Fisk as Kristy, Rachel Leigh Cook as Mary Anne, Larisa Oleynik as Dawn, and Bre Blair as Stacey. Scholastic co-produced the film and was involved heavily in the production. Jane Startz, executive vice president of Scholastic Productions, helped to hire a screenwriter, took part in script revisions, and hung out on set. “Scholastic wanted to make sure The Baby-sitters Club movie would have the same feel as the books,” director Melanie Mayron told the Los Angeles Times. “[Jane] was like a partner and I was grateful to have her … she’d point to [one of the characters] and say, ‘She wouldn’t do that.’”

Martin, too, worked on the film, helping to create the plot and weighing in on the script when necessary. “I was involved from the very beginning, talking to producers and working on the general idea for the plot,” she told Publisher’s Weekly in 1995. “I saw the script through its many, many stages. I’ve seen the movie twice now and am very pleased with it.” The movie, which had a budget of $6.5 million, made a little under $10 million domestically.

15. When Martin wrote a prequel in 2010, Scholastic reissued the first seven Baby-sitters Club books—with a few changes.

By 2009, all of the Baby-sitters Club titles were out of print. In 2010, Martin released a prequel to the events of BSC called The Summer Before. “It was fun to explore their lives in the prequel,” Martin told Amazon, “and to figure out what led the girls to form the Baby-sitters Club, something that would eventually change their lives. It was like a reunion with friends—friends who haven’t changed a bit.”

To celebrate the prequel, Scholastic released the first seven books in the series with new covers and important updates: References to outdated technology like Walkmans were removed; Stacey’s perm was replaced by an “expensive haircut.” But they didn’t go all out. “We felt if we set ourselves going down the road of cell phones it would have been crazy, so we didn’t do that, but we updated stuff about Stacey’s diabetes, and we got rid of stuff like VCRs,” Martin told Elle.

16. Martin has some ideas about where The Baby-sitters Club girls ended up.

Though The Baby-sitters Club is being reborn via Netflix, Martin is still often asked about what her characters are doing now, and though she doesn’t have any hard answers, she is willing to speculate. In 2010, she told The Washington Post in 2010 that Kristy is likely a politician or a CEO, while Mary Anne decided to become a teacher; Stacey works in fashion and business and Claudia in art (obviously). Jessi is a dancer, and Dawn is a permanent California girl—but Martin isn’t sure what Mallory would be up to. Maybe, she speculated, she would go on to write a series of books for children.