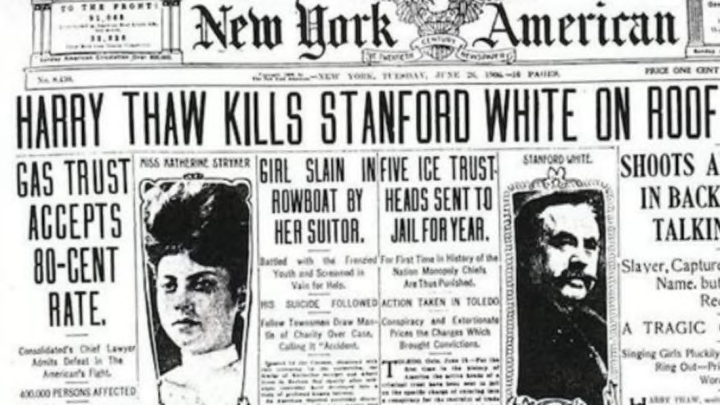

On the balmy evening of June 25, 1906, during the performance of a musical at Madison Square Garden, railroad heir Harry K. Thaw walked up to the table of architect Stanford White and shot him in the head. This led to what the newspapers dubbed “the Trial of Century.” The 20th century was young, and the media frenzy would arguably be eclipsed by other "trials of the century"—Sacco and Vanzetti, the Rosenbergs, Charles Manson, O.J. Simpson—but it did introduce the public to many of the concepts that would become well-known to tabloid readers and Court TV viewers, including the insanity plea, the media circus, the sequestering of jurors, and the buying of a better judicial outcome by the rich. At the heart of the matter was the era’s concept of a woman’s honor.

1. THAW HAD A HISTORY OF MENTAL ILLNESS AND LIVED A DECADENT LIFE OF LEISURE.

The son of Pittsburgh railroad baron William Thaw, Harry K. Thaw was born in 1871. As a child, he was prone to screaming tantrums and outbursts of bodily flailing that exhausted his mother, Mary, and their household staff. Author Michael Macdonald Mooney writes in Evelyn Nesbit and Stanford White: Love and Death in the Gilded Age that a teacher from his boarding school described Thaw as “sullen, unreasonable, and unhappy” and “absolutely unintelligible.” In his mid-teens, he performed a prank at his school, Wooster College, where he paid a burlesque troupe visiting town to wear leggings of the school colors.

Because of his son’s temperament, Thaw’s father decided against a giving his son full control of his inheritance and instead assigned a trust to dole out $2400 a year to him in his will. After William died in 1889, his indulgent mother made sure her son's annual allowance was $80,000.

Thaw briefly enrolled at Harvard, where he hosted all-night poker games and chased a cab driver with a shotgun for allegedly shorting him change. He was expelled for “moral turpitude,” according to Mooney. Soon after, the stone-faced and bug-eyed young man gave up all pretense of work or study and instead traveled the U.S. and Europe, mingling in high society, visiting brothels, getting into skirmishes, and using cocaine. He threw lavish parties, giving away jewelry pieces worth thousands as party favors to attract women. He was also a sadist and abused his partners.

2. WHITE WAS A PROMINENT ARCHITECT AND LADIES MAN.

The victim of the crime, Stanford White, was one partner of the New York City architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, which came to prominence designing country and seaside mansions. From there, the company produced several neoclassical landmarks, including the Boston Library, the Washington Square Arch, Manhattan’s original Pennsylvania Station, the Brooklyn Museum, the Morningside Heights campus of Columbia University, and the original Madison Square Garden, where White would be murdered.

The firm’s success allowed White, unmistakable for his tall build and red hair and mustache, to hobnob with the city’s business, artistic, and government elite. By the late 1890s, he “was the city’s leading architect,” according to Mooney, and relished his role as man about town. “He was the leader of its leading artists, promoter of its best institutions, impresario of its most colorful entertainments, founder and organizer of its most colorful clubs, and often architect of them as well,” wrote Mooney. “His immense energies were spent day and night in an attempt to give character to the city’s wealth.”

White kept an elaborately decorated tower residence on West 24th Street, which he stocked with exotic foods and wines and furnished with such novelties as a red velvet swing extending from a ceiling. Though married at 31, he frequently entertained and seduced models and chorus girls there.

3. THOUGH THE TWO BARELY KNEW EACH OTHER, THAW BLAMED WHITE FOR HIS SOCIAL FAILINGS.

Thaw was a frequent visitor to New York City and sought entry into the elite social circles. He felt White blocked his entry due to a perceived faux pas.

After his trial, Thaw authored a memoir entitled The Traitor, its title a reference to White, who is called that word throughout. Thaw recounted what he said was his first encounter with the architect. A mutual acquaintance invited Thaw to a party at White’s 24th Street residence, where Thaw claimed White mistakenly associated his group with a drunk party-goer who declared the food and wine “rotten.” After that, Thaw applied to several New York gentlemen’s clubs and was rejected or soon kicked out for erratic behavior. The Union League Club of New York revoked his membership after he rode a horse up the club’s entranceway to herald his arrival. According to Paula Uruburu in her book American Eve, in Thaw’s mind, every denial, ejection, and snub was due to the hidden influence of the offended White, who was everything Thaw was not but wanted to be: successful, liked, influential.

Then, at one of Thaw’s parties for playboys and showgirls, an actress took his nervousness in her presence as embarrassment to be seen with her. She retaliated by convincing the women to vacate the party for one at White’s. According to Uruburu, “a livid Harry blamed White for yet another public indignity.” The slight and the actress’s exodus made it into the society pages, humiliating Thaw.

4. THAW AND WHITE WERE INVOLVED WITH THE SAME WOMAN.

Known for the way her long hair draped down her back in a shape like a question mark, Evelyn Nesbit began working as a model in her early teens. First in Philadelphia and then New York City, she spent hundreds of hours in front of illustrators and photographers, while chaperoned by her mother. Her face appeared on an endless array of postcards, magazine covers, fine art pieces, and advertisements. Some have dubbed her the first supermodel.

By age 16, Nesbit had already become bored of this work and started a career as a chorus girl on Broadway. Inevitably, she made the acquaintance of Stanford White.

According to American Eve, after a few lunches, White managed to get her to his West 24th Street residence without her mother’s company. She would later testify that he charmed her with the intricacies of his home (the detail of Nesbit trying the red velvet swing would become infamous in tabloid lore), plied her with champagne, and assaulted her while she was passed out.

Soon after, a mysterious “Mr. Monroe” (sometimes Munroe) began sending gigantic bouquets of flowers to Nesbit at the theater hosting the show The Wild Rose, but they weren’t from White—they were from Harry Thaw, who had attended 40 performances of the show. A mutual friend introduced the two at a restaurant. In her 1914 memoir, Nesbit recalls he tried to compliment her by favorably comparing her to another chorus girl, which put her off. She “had no desire to meet him again,” but Thaw continued to shower her with gifts and money.

According to American Eve, Nesbit refused marriage proposals from Thaw for years as she drifted through romantic relationships, including an on-again-off-again fling with White. In 1903, after undoing surgery for appendicitis (which has long been rumored to have been an illegal abortion), she accepted an invitation from Thaw to tour Europe. Thaw questioned her a few times about her relationship with White, and even signed a visitors book at the birthplace of Joan of Arc with, “She would not have been a virgin if Stanford White had been around.” After he interrogated Nesbit in a Paris hotel room, she told him about the assault in White's 24th Street home. For the remainder of the trip, Thaw was both physically and emotionally abusive towards Nesbit.

Nesbit and Thaw married soon after and took residence in his family estate in Pittsburgh. The marriage only increased Thaw’s obsession with White. He became convinced that White had hired the Eastman Gang to kill him and began to carry a gun.

5. THE MURDER HAPPENED DURING A MUSICAL, WHICH DIDN’T STOP AFTER THE SHOOTING.

In June 1906, the Thaws returned to New York and saw the show Mam'zelle Champagne at Madison Square Garden, which was then an open-air rooftop theater and bar.

The account of the murder in Mooney's Love and Death in the Gilded Age can be summarized like so: Thaw knew that White had a usual table at the venue. During a number titled “I Could Love a Thousand Girls,” he walked up to White, took out a revolver concealed in his overcoat, and shot him three times. White stood and then fell over the table in a pool of blood. The music stopped and silence overtook the room. Then someone laughed, mistaking the act as part of the show (two of the characters in the play had talked about a “burlesque duel” moments before). The stage manager ordered the orchestra and dancers to continue as Thaw stood over his victim. Only when women began fainting did the stage manager announce that “a most serious accident has occurred” and ordered the audience to “quietly” leave. Thaw rode the elevator with others, muttering, “He deserved it. I can prove it.” A police officer waited for him on the ground floor.

In The Traitor, Thaw wrote, “The agony of Evelyn in the years of her girlhood formed the prelude to a long continuous drama of sorrow, the murk and gloom of which was never illuminated by a ray of sunshine until what occurred on the roof of Madison Square Garden and Stanford White fell dead.”

6. THE TRIAL WAS AN INSTANT MEDIA CIRCUS.

Newspapers had a segment of reporters dismissively called “sob sisters” or “the pity patrol.” These were female journalists whose only career path in a male-dominated field was reporting stories of wronged women for female readers, the more melodramatic the better. The story of the deadly love triangle with an abused starlet at one corner was exactly what they sought. According to American Eve, Hearst and Pulitzer both assigned sob sisters to the story. Papers in Pittsburgh, home of the Thaw family, also ran daily coverage. According to Lloyd Chiasson in his book The Press on Trial, a Western Union office was opened in the courthouse just to help reporters wire dispatches.

Soon, reporters uncovered past exploits of the man they dubbed “Bathtub Harry” for his habit of scalding women (and apparently, once, a bellboy whom the Thaws paid hush money). There was a counter-effort, financed by Mary Thaw, to portray her son as a defender of womanly virtue. Letters to the editor praising Thaw as such started appearing in newspapers. According to The Press on Trial, Mary Thaw even commissioned the writing of a three-character play based on the events (two of the characters were named Harold Daw and Stanford Black), portraying White as a perverted hedonist.

7. THE TRIAL WAS ONCE OF THE FIRST INSTANCES OF JURY SEQUESTRATION.

Due to the intense interest in the case, the judge ordered the jury to abstain from all media and interacting with reporters, according to The Press on Trial. It was one of the first instances of jury sequestration in American history.

8. THOMAS EDISON ORDERED A QUICKLY-PRODUCED MOVIE ADAPTATION.

One week after the murder, Thomas Edison's studio commissioned a film entitled Rooftop Murder to be shown at nickelodeons.

9. THAW’S ATTORNEYS ARGUED TEMPORARY INSANITY.

Mary Thaw committed $1 million to her son’s defense. They both feared he’d be locked up indefinitely if he simply pled insanity, and they couldn’t stomach the idea of him being dubbed an incurable madman. So their legal team came up with a peculiar defense: temporary insanity. Learning about White’s assault of the woman who was now his wife stirred a state of insanity in Thaw. Even though he lived with the knowledge for three years beforehand, he was insane when he pulled the trigger but sane both before and after.

They eventually settled on Delphin Delmas of San Francisco (who had never lost a case) as lead attorney. The trial started on January 23, 1907, and Delmas brought in a stream of doctors and psychiatrists to testify to Thaw’s mindset. A reluctant Nesbit, still financially supported by the Thaws, testified about White’s abuse.

In his closing statements, Delmas memorably coined a new phrase, declaring, “if you desire a name for this species of insanity let me suggest it—call it Dementia Americana. That is the species of insanity which makes every American man believe his home to be sacred; that is the species of insanity which makes him believe the honor of his daughter is sacred; that is the species of insanity which makes him believe the honor of his wife is sacred.” He implied any decent man would become homicidally insane in response to an act like White’s. Prosecutor William Jerome shot back that the murder was “a common, vulgar, everyday, tenderloin homicide.”

10. THAW WAS FOUND NOT GUILTY BUT DIDN’T WALK FREE IMMEDIATELY.

In the first trial, the jury was deadlocked, with seven in favor of conviction and five voting to acquit. In the second trial, Thaw’s new attorney, Martin W. Littleton went a new direction, claiming that his client was completely insane. The jury found him not guilty by reason of insanity, and the judge confined him to the Matteawan State Hospital “until thence discharged by due course of law.” Expected to be set free, Thaw seethed with anger.

According to American Eve, Thaw was released in 1915, the same year Evelyn Nesbit filed for divorce. Two years later, Thaw kidnapped and assaulted a male 19-year-old acquaintance and was returned to an asylum until 1924. Afterwards, Thaw avoided legal trouble—save a lawsuit from partners in a short-lived film production business for nonpayment—and lived until the age of 76.