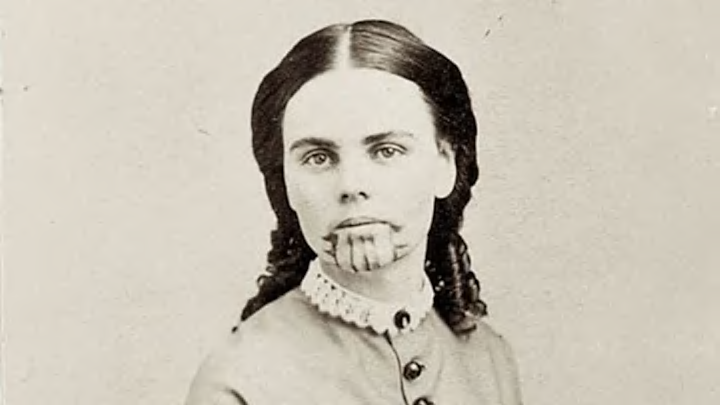

About a century and a half ago, some Native American tribes of the Southwest used facial tattoos as spiritual rites of passage. Through a series of strange tragedies (and some possible triumphs), a white Mormon teenager who was traveling with her family through the area in the mid-19th century ended up sporting one too, a symbol of a complicated dual life she could never quite shake.

In 1851, the Oatman family, having broken from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was traveling through southeastern California and western Arizona, looking for a place to settle. As newly inducted Brewsterites—followers of Mormon rebel James C. Brewster—they’d been advised that California was, in fact, the true “intended gathering place” for Mormons, rather than Utah.

The group of approximately 90 followers had left Independence, Missouri, in the summer of 1850, but when they arrived in the New Mexico Territory, the party split, with Brewster’s faction taking the route to Santa Fe and then south to Socorro, and Royce (sometimes spelled Roys) Oatman leading a group to Socorro and then over to Tucson.

When the remaining members of the Oatman-led party approached Maricopa Wells, in modern-day Maricopa County, Arizona, they were warned not only that the southwestern trail ahead was barren and dangerous, but that the Native tribes in the region were famously violent toward whites. To continue, it was made clear, was to risk one’s life.

The other families elected to stay in Maricopa Wells until they had recuperated enough to make the journey, but Royce Oatman chose to press on. And that’s how Royce, his wife Mary, and their seven children, aged 1 to 17, found themselves trekking through the most arid part of the Sonoran Desert on their own.

Sure enough, about 90 miles east of Yuma, on the banks of the Gila River, the family was waylaid by a group of Native Americans, likely Yavapai, who asked them for food and tobacco. The details of what happened next aren’t known, but the encounter somehow turned into an attack. Apparently, all of the Oatmans were murdered—all except Lorenzo, age 15, who was beaten unconscious and left for dead.

Or so it seemed. When Lorenzo came to, he found six bodies, not eight: Two of his sisters, 14-year-old Olive and 7-year-old Mary Ann, were nowhere to be seen. Badly injured, Lorenzo walked to a settlement and had his wounds treated, then rejoined the group of other Mormon emigrants, who returned with the teenager to the scene of the violence. Because the volcanic soil was rocky and difficult to dig, it was not possible to bury the Oatmans, so cairns were built around their bodies instead.

But where were Olive and Mary Ann?

Captured

The Yavapai had taken the sisters, very much alive, to their village about 60 miles away, along with selected prizes from the Oatmans’ wagon. Tied with ropes, the girls had been made to walk for several days through the desert, which triggered serious dehydration and weakened them in general. When they asked for water or rest, they were poked with lances and forced to keep walking. Once they reached the Yavapai village, the girls were treated as slaves, made to forage for food and firewood. The tribe’s children would burn them with smoldering sticks while they worked, and they were beaten often. The girls, Olive later said, were sure they’d be killed.

The girls lived as the Yavapai’s servants for approximately a year, until some members of the Mohave tribe, with whom the group traded, stopped by one day and expressed interest in the Oatmans. The Yavapai ended up swapping them for some horses, blankets, vegetables, and an assortment of trinkets. Once the deal was done, the sisters were again made to walk for several days through the desert, this time north to the Mohave village, near the not-yet-founded city of Needles, California, and unsure of their fates all the while.

Members of the Tribe

Things improved significantly once the girls were on Mohave land: Mary Ann and Olive were taken in straight away by the family of a tribal leader, Espanesay, and adopted as members of the community. Both children had their chins and upper arms tattooed with blue cactus ink in thick lines, like everybody else in the tribe, to ensure that they’d be recognized as tribal members in the afterlife and—interestingly, in this case—reunited with their ancestors.

The scenery was upgraded, too; the Mohave village was located in an idyllic valley lined with cottonwoods and willows, set along the Colorado River. No longer enslaved, they were not forced to work, and “did pretty much as they pleased,” according to an 1856 newspaper account. They were also given land and seeds to raise their own crops. The two sisters were also given their clan’s name, Oach, and they formed strong bonds with the wife and daughter of their adopted family, Aespaneo and Topeka, respectively. For the rest of her life, Olive spoke of the two women with great affection, saying that she and Mary Ann were raised by Espanesay and Aespaneo as their own daughters.

The girls seemingly considered themselves assimilated into the Mohave community—so much so that in February 1854, when approximately 200 white railroad surveyors spent a week trading and socializing with the Mohave as part of the Whipple Expedition, neither Olive nor Mary Ann revealed herself as an abductee or asked the men for help. (The girls, unaware that their brother Lorenzo survived the attack in 1851, may have believed they had no living relatives, which could have added another incentive for them to stick with the tribe.)

A few years after their initial capture, a drought in the Southwest caused a major crop shortage and Mary Ann subsequently starved to death, along with many others in the Mohave tribe. She was approximately 10 years old. Olive later said she only made it through the famine herself because she was specifically cared for by Aespaneo, her foster mother, who fed her in secret while the rest of the village went hungry.

A Complicated Rescue

In 1855, a member of the nearby Quechan tribe named Francisco showed up at the Mohave village with a message from the federal government of the United States. Authorities at Fort Yuma had heard rumors about a young white woman living with the Mohave, and the post commander was asking them to either return her or explain why she would choose not to return. The Mohave first responded by refusing to respond, then sequestering Olive for safekeeping. Next, they tried denying that she was white. When this didn’t work, they began to weigh their affection for Olive against their fear of reprisal by the U.S. government, which had threatened (via Francisco) to destroy the tribe if Olive was not handed over.

Francisco, as the middleman, was concerned for his neighboring tribe’s safety—and possibly his own—and persisted in his attempts. The negotiations were lengthy and included Olive herself at some points. As she was quoted in one later account of her ordeal:

“I found that they had told Francisco that I was not an American, that I was from a race of people much like the Indians, living away from the setting sun. They had painted my face, and feet, and hands of a dun, dingy color, unlike that of any race I ever saw. This they told me they did to deceive Francisco; and that I must not talk to him in American [sic]. They told me to talk to him in another language, and to tell him that I was not an American. They then waited to hear the result, expecting to hear my gibberish nonsense, and to witness the convincing effect upon Francisco. But I spoke to him in broken English, and told him the truth, and also what they had enjoined me to do. He started from his seat in a perfect rage, vowing that he would be imposed upon no longer.”

The jig was up. Some of the Mohave were furious with Olive for disobeying orders and went as far as to suggest that she should be killed as punishment. But her foster family opposed the idea, and Francisco and the Mohave eventually hammered out an offer: Olive would be ransomed back to the U.S. government in exchange for a horse and some blankets and beads. Olive’s adoptive sister, 17-year-old Topeka, would join her on the trek to ensure the goods were handed over.

When Olive left, Aespaneo wept as if she were losing her own child. The journey to Fort Yuma took 20 days, and the party arrived there on February 22, 1856. When she was approached by the fort’s commander, Olive cried into her hands. Before she was permitted to enter the fort, she was loaned a Western-style dress by an officer’s wife, as she and Topeka arrived wearing only traditional Mohave skirts, with their chests bare. She was also made to wash her painted face as well as her hair, which was dyed with the black sap of a mesquite tree. When asked her given name, she said it was “Olivino,” and told the commander that she was 11 when abducted by the Yavapai, not 14, among other incorrect details. Once she was cleaned up, Olive was received by a cheering crowd.

By the time Olive was sent to Fort Yuma, five years had passed since the murder of most of the Oatman family and the girls’ initial capture. She was soon informed that her brother, Lorenzo, had also survived the massacre; they met soon after, with newspapers across the western U.S. reporting the event as headline news.

Missing Pieces

However, accounts of Olive’s time among the Native American tribes are problematic for several reasons. In 1857, a year after Olive’s return, a Methodist minister named Royal Stratton interviewed Olive at length and wrote a bestselling book, first titled Life Among the Indians and later renamed Captivity of the Oatman Girls, chronicling the Oatman sisters’ half-decade with the Native peoples. Olive later lectured widely about her experiences in support of the book, but not all of her details added up. In Stratton’s book, Olive stated that neither the Yavapai nor the Mohave ever “offered the least unchaste abuse to me,” and she denied all allegations of rape or even sexual activity with any members of the tribe. However, her best childhood friend, Susan Thompson—whom Olive later befriended again—believed that Olive had married a Mohave man and given birth to two boys, and that her depression upon returning to non-tribal society was actually grief. Olive denied this.

Olive also displayed some duplicity in her lectures: She repeatedly told audiences that she was tattooed in order to identify her if she escaped from the tribe, neglecting to mention that most Mohave women had facial tattoos, some in the exact same design as Olive’s. She also identified her captors as Apache, not Yavapai, which most modern historians believe to be untrue. (However, Apache was a common term to describe several Southwestern tribes, so she may have been using the word in a general sense.)

Stratton’s book also includes long stretches of fervid anti-Native rhetoric, and she signed off on this portrayal of them via her lectures, frequently calling them “savages” herself. But this view wasn’t really corroborated by her private actions. After she moved to southern Oregon with her brother, she is said to have wept and paced the floor at night, and friends described her as deeply unhappy in her new life, and longing to return to the Mohave. She even went to New York when she heard that Irataba, a Mohave dignitary, would be traveling there in 1864. Evidently, Olive remembered him fondly enough to reminisce about tribal life with him, a conversation carried on in the Mohave language. (Irataba told Olive that Topeka still missed her and hoped for her return.) She later said “we met as friends.”

Forever Marked

Her time spent with the Indigenous communities troubled the rest of Olive Oatman’s life, since she was perceived as—literally—a marked woman. If she had, in fact, been married to a Native man—or even if she’d frolicked with any of them—the pressure to hide it would be serious, now that she was back in conservative Western society, where a woman’s virginity was sacrosanct. Even friendships between white and Native American people were frowned upon, to say nothing of sexual relationships.

Olive, who had barely remembered how to speak English at first, became a household name within a month, with the news of the rescue of the “young and beautiful American girl” appearing in newspapers across the nation. After the success of Stratton’s biography, she was a famous person, living under the celebrity microscope. Journalists seemed to especially focus on Olive’s appearance, pointing out her beauty as often as her tattoo. But despite her consistent denial of having had any Native husbands or lovers, the rumor stuck, thanks partially to a front-page story in the Los Angeles Star—which reported in 1856, a month before Olive’s return, that both Oatman girls were discovered alive and married to Mohave chiefs.

In November 1865, Olive married John B. Fairchild, a wealthy rancher-turned-banker, in Rochester, New York, after meeting him through the lecture circuit. She subsequently abandoned her speakking tours. A few years later, the couple settled in Sherman, Texas, and adopted a baby girl named Mamie. Olive never seemed to have found happiness, though, battling depression and chronic headaches for decades. On the rare occasion she left her home, she attempted to cover her blue tattoo with makeup or veils.

Olive died of a heart attack in 1903, aged 65, and is buried in Sherman with her husband. Letters found after she died told of the psychological damage she suffered, which was often ascribed to the murder of her family, but could just as fairly be attributed to having her second family, the one she built among the Mohave, wrenched away from her.

Though mostly forgotten today, Olive Oatman is still occasionally paid homage, particularly via the character of Eva Toole on the AMC show Hell on Wheels, who sported a very similar backstory and tattoo. Olive’s story was also loosely told in a 1965 episode of the television show Death Valley Days, starring Shary Marshall as Olive—and featuring Ronald Reagan as an Army colonel who helps her brother locate her. A 2009 biography of Oatman, The Blue Tattoo, tells her story much more faithfully. She’s also the namesake of the city of Oatman, Arizona, located on Route 66, near the Colorado River—and near the site where Oatman was released after spending her adolescence with the Mohave.

Read More About the 19th Century:

A version of this story originally ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2025.