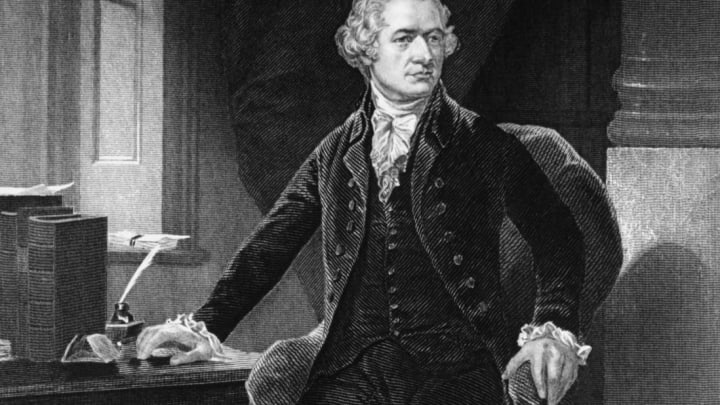

In August 1772, a hurricane ravaged the West Indies—and a young Alexander Hamilton picked up a pen to write about it. The resulting letter would inspire the residents of the island where Hamilton lived to pool their money for a scholarship to send him to the future United States of America … and into the history books.

It was a week after the hurricane when the future secretary of the Treasury, who was working as a clerk on St. Croix, wrote the life-altering letter. As Ron Chernow writes in the biography Alexander Hamilton, the 17-year-old had just attended a sermon by Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian minister who had arrived in St. Croix earlier that year and had taken the young man under his wing. Inspired, Hamilton picked up a pen and wrote of the hurricane's disastrous effects. He intended only to send it to his father, James A. Hamilton, who was living on St. Kitts after abandoning his illegitimate family (Alexander's mother, Rachel, was married to another man when she took up with James) more than six years earlier. But when Hamilton showed Knox what he'd written, the minister had other ideas.

Knox had studied divinity at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), and was ordained by the president of the institution—one Aaron Burr Sr. But Knox wasn't just a minister. He had a number of other careers, including a gig editing The Royal Danish American Gazette when its regular editor was out of town. He persuaded Hamilton—who had already written a few poems that had appeared, without a byline, in the paper—to publish the letter. It appeared in the October 3 edition, and Knox penned a forward of sorts, noting that the letter “fell by accident into the hands of a gentleman, who, being pleased with it himself, shewed it to others to whom it gave equal satisfaction, and who all agreed that it might not prove unentertaining to the Publick.” It was so late, Knox wrote, because of “The Author’s modesty in long refusing to submit it to Publick view.”

“Honoured Sir,” Hamilton began the letter, “I take up my pen just to give you an imperfect account of one of the most dreadful Hurricanes that memory or any records whatever can trace, which happened here on the 31st ultimo at night.”

“It began about dusk, at North, and raged very violently till ten o’clock. Then ensued a sudden and unexpected interval, which lasted about an hour. Meanwhile the wind was shifting round to the South West point, from whence it returned with redoubled fury and continued so ’till near three o’clock in the morning. Good God! what horror and destruction. Its impossible for me to describe or you to form any idea of it. It seemed as if a total dissolution of nature was taking place. The roaring of the sea and wind, fiery meteors flying about it in the air, the prodigious glare of almost perpetual lightning, the crash of the falling houses, and the ear-piercing shrieks of the distressed, were sufficient to strike astonishment into Angels. A great part of the buildings throughout the Island are levelled to the ground, almost all the rest very much shattered; several persons killed and numbers utterly ruined; whole families running about the streets, unknowing where to find a place of shelter; the sick exposed to the keeness of water and air without a bed to lie upon, or a dry covering to their bodies; and our harbours entirely bare. In a word, misery, in all its most hideous shapes, spread over the whole face of the country. A strong smell of gunpowder added somewhat to the terrors of the night; and it was observed that the rain was surprizingly salt. Indeed the water is so brackish and full of sulphur that there is hardly any drinking it. “My reflections and feelings on this frightful and melancholy occasion, are set forth in the following self-discourse. “Where now, oh! vile worm, is all thy boasted fortitude and resolution? What is become of thine arrogance and self sufficiency? Why dost thou tremble and stand aghast? How humble, how helpless, how contemptible you now appear. And for why? The jarring of elements—the discord of clouds? Oh! impotent presumptuous fool! how durst thou offend that Omnipotence, whose nod alone were sufficient to quell the destruction that hovers over thee, or crush thee into atoms? See thy wretched helpless state, and learn to know thyself. Learn to know thy best support. Despise thyself, and adore thy God. How sweet, how unutterably sweet were now, the voice of an approving conscience; Then couldst thou say, hence ye idle alarms, why do I shrink? What have I to fear? A pleasing calm suspense! A short repose from calamity to end in eternal bliss? Let the Earth rend. Let the planets forsake their course. Let the Sun be extinguished and the Heavens burst asunder. Yet what have I to dread? My staff can never be broken—in Omnip[o]tence I trusted. He who gave the winds to blow, and the lightnings to rage—even him have I always loved and served. His precepts have I observed. His commandments have I obeyed—and his perfections have I adored. He will snatch me from ruin. He will exalt me to the fellowship of Angels and Seraphs, and to the fullness of never ending joys. But alas! how different, how deplorable, how gloomy the prospect! Death comes rushing on in triumph veiled in a mantle of tenfold darkness. His unrelenting scythe, pointed, and ready for the stroke. On his right hand sits destruction, hurling the winds and belching forth flames: Calamity on his left threatening famine disease and distress of all kinds. And Oh! thou wretch, look still a little further; see the gulph of eternal misery open. There mayest thou shortly plunge—the just reward of thy vileness. Alas! whither canst thou fly? Where hide thyself? Thou canst not call upon thy God; thy life has been a continual warfare with him. Hark—ruin and confusion on every side. ’Tis thy turn next; but one short moment, even now, Oh Lord help. Jesus be merciful! Thus did I reflect, and thus at every gust of the wind, did I conclude, ’till it pleased the Almighty to allay it. Nor did my emotions proceed either from the suggestions of too much natural fear, or a conscience over-burthened with crimes of an uncommon cast. I thank God, this was not the case. The scenes of horror exhibited around us, naturally awakened such ideas in every thinking breast, and aggravated the deformity of every failing of our lives. It were a lamentable insensibility indeed, not to have had such feelings, and I think inconsistent with human nature. Our distressed, helpless condition taught us humility and contempt of ourselves. The horrors of the night, the prospect of an immediate, cruel death—or, as one may say, of being crushed by the Almighty in his anger—filled us with terror. And every thing that had tended to weaken our interest with him, upbraided us in the strongest colours, with our baseness and folly. That which, in a calm unruffled temper, we call a natural cause, seemed then like the correction of the Deity. Our imagination represented him as an incensed master, executing vengeance on the crimes of his servants. The father and benefactor were forgot, and in that view, a consciousness of our guilt filled us with despair. But see, the Lord relents. He hears our prayer. The Lightning ceases. The winds are appeased. The warring elements are reconciled and all things promise peace. The darkness is dispell’d and drooping nature revives at the approaching dawn. Look back Oh! my soul, look back and tremble. Rejoice at thy deliverance, and humble thyself in the presence of thy deliverer. Yet hold, Oh vain mortal! Check thy ill timed joy. Art thou so selfish to exult because thy lot is happy in a season of universal woe? Hast thou no feelings for the miseries of thy fellow-creatures? And art thou incapable of the soft pangs of sympathetic sorrow? Look around thee and shudder at the view. See desolation and ruin where’er thou turnest thine eye! See thy fellow-creatures pale and lifeless; their bodies mangled, their souls snatched into eternity, unexpecting. Alas! perhaps unprepared! Hark the bitter groans of distress. See sickness and infirmities exposed to the inclemencies of wind and water! See tender infancy pinched with hunger and hanging on the mothers knee for food! See the unhappy mothers anxiety. Her poverty denies relief, her breast heaves with pangs of maternal pity, her heart is bursting, the tears gush down her cheeks. Oh sights of woe! Oh distress unspeakable! My heart bleeds, but I have no power to solace! O ye, who revel in affluence, see the afflictions of humanity and bestow your superfluity to ease them. Say not, we have suffered also, and thence withold your compassion. What are you[r] sufferings compared to those? Ye have still more than enough left. Act wisely. Succour the miserable and lay up a treasure in Heaven. I am afraid, Sir, you will think this description more the effort of imagination than a true picture of realities. But I can affirm with the greatest truth, that there is not a single circumstance touched upon, which I have not absolutely been an eye witness to. Our General [Ulrich Wilhelm Roepstorff, Governor General of St. Croix] has issued several very salutary and humane regulations, and both in his publick and private measures, has shewn himself the Man.”

No one cared how late the letter was: The businessmen of St. Croix were so moved by Hamilton’s account of the tragedy that they demanded to know his identity and took up a collection to send him to America to be educated. (As Chernow points out, this was incredible given the state of the island, which was ravaged by the storm and wouldn’t recover for years.) Sometime in late 1772 or early 1773, Hamilton boarded a ship to the United States, never to return to the West Indies.

The letter changed Hamilton's life, and in a way, it also changed Lin-Manuel Miranda's: When he read about the letter and its consequences in Chernow’s book, a lightbulb went off. “I was like, This is an album—no, this is a show ... It was the fact that Hamilton wrote his way off the island where he grew up. That’s the hip-hop narrative,” he told Vogue in 2015. “So I Googled ‘Alexander Hamilton hip-hop musical’ and totally expected to see that someone had already written it. But no. So I got to work.” The result, of course, was the Broadway musical Hamilton. Miranda won a MacArthur Genius Grant and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama; his musical won seven Drama Desk awards (as well as a special award for the choreographer), a Grammy, and 11 Tony Awards.

Miranda used the essay to create one of the most dramatic moments in Hamilton. In “Hurricane,” the titular character sings, “When I was 17 a hurricane destroyed my town/I didn’t drown/I couldn’t seem to die/I wrote my way out/Wrote everything down far as I could see/I wrote my way out/I looked up and the town had its eyes on me/They passed a plate around, Total strangers/Moved to kindness by my story/Raised enough for me to book passage on a ship that was New York bound…” His writing has always served him well and worked in his favor, the character reasons. He uses that reasoning to justify writing the Reynolds Pamphlet, which exposed his affair with Maria Reynolds in excruciating detail and kicked off the first political sex scandal in American history … but that’s a story for another time.