The concept of luck seems to be a catchall for things we just can’t explain—like surviving deadly experiences or happening upon world-altering inventions. Even though we don’t know why, some people just seem to have more luck than others.

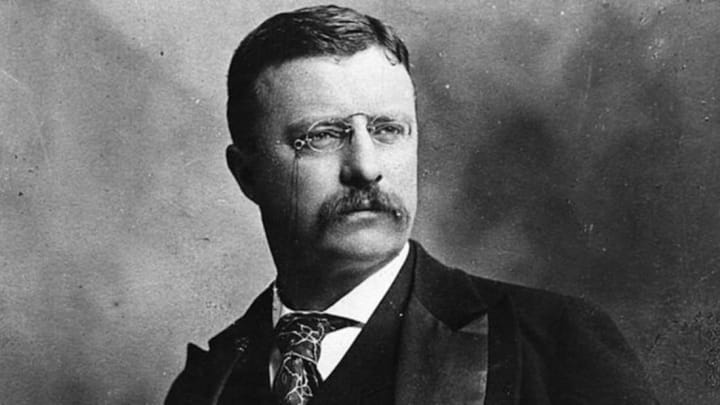

1. TEDDY ROOSEVELT

Former U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt had a reputation for being a stubborn fighter, which might have some weight considering he survived an up-close assassination attempt and lived to tell the tale (or rather, continue on with his day). On October 14, 1912, Roosevelt was leaving a Milwaukee hotel for a campaign stop, where he was shot in the chest by John Schrank, a New York City saloonkeeper. Schrank’s bullet was lodged in Roosevelt’s rib, but it had been slowed by the 50-page speech and eyeglass case tucked in his coat pocket. Roosevelt refused medical attention and addressed his audience with a 90-minute speech, saying “It takes more than that to kill a bull moose.”

2. VESNA VULOVIC

Serbian flight attendant Vesna Vulovic was incorrectly scheduled to work on January 26, 1972. Mistaken for another coworker named Vesna, Vulovic went to work greeting passengers onboard a flight from Copenhagen back to Yugoslavia. But within an hour, she laid among aircraft wreckage in Czechoslovakia, the sole survivor of a plane explosion that killed 27 people. In the crash landing, Vulovic allegedly fell 33,300 feet, trapped inside the plane’s fuselage. While she was initially paralyzed and sustained a variety of broken bones and fractures (she spent 16 months in the hospital after the incident), Vulovic fully recovered without any memory of the fall. The Guinness Book of World Records recognized Vulovic for the "Highest Fall Survived Without a Parachute," though recent investigators believe crash details were altered for propaganda uses.

3. ADOLPHE SAX

Belgian musician and inventor Adolphe Sax is best known for his reedy, namesake instrument: the saxophone. The son of a carpenter and instrument maker, Sax’s early 1800s childhood was put to use perfecting already popular instruments like the clarinet and using improvements to dream up his own inventions (cue the saxtuba and saxhorn). While Sax is known for his contributions to musical history, what many don’t know is how often he escaped death. As a toddler, Sax fell the “height of three floors” before hitting his head on a rock, and was initially believed to be dead. By 3 years old, he had drank a bowl of sulfuric acid and swallowed a needle. Sax also endured serious burns from a gunpowder explosion and a cast iron frying pan, later almost suffocating in his sleep from heavy varnish fumes. Falling cobblestones and a near-drowning in a river round out some of Sax’s childhood mishaps. Sax’s mother, Marie-Joseph Sax, certainly noticed the pattern. “He’s a child condemned to misfortune," she once said. "He won't live." (She was wrong. He lived to be 79.)

4. ROY SULLIVAN

The odds of being struck by lighting during your lifetime are 1 in 12,000. But this probably came as little comfort to park ranger Roy Sullivan, who survived seven lightning strikes over the course of 35 years. Sullivan’s first encounter with lightning occurred in 1942 when he ran through a storm in Shenandoah National Park. Additional lightning hits followed in 1969, 1970, 1972, 1973, 1976, and 1977. Sullivan’s relationship with lightning led to a variety of jokes and rumors, including a rumor that he kept lightning rods on his four-poster bed. Sullivan died in 1983 at the age of 71, but not from lightning—sadly, it was from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

5. LUDGER SYLBARIS

Ludger Sylbaris was known in the early 1900s for his sideshow tales of surviving a volcanic eruption on the island of Martinique. And while some of his embellishments (suggesting he was the only survivor of the eruption) weren’t quite true, Sylbaris did in fact survive Mount Pelée’s eruption in 1902—and it’s because he was in jail. Sylbaris was known for drinking and fighting, which landed him in a stone jail cell in the town of Saint-Pierre. The morning after his arrest, Mt. Pelée erupted, destroying the town and killing an estimated 30,0000 people. Sylbaris was shielded from flying debris and much of the heat in his partially underground jail cell, but still had severe burns when he was discovered by rescue teams four days later. Sylbaris used his near-death experience for a chance at fame, touring with the Barnum and Bailey Circus as “The Man Who Lived Through Doomsday.”

6. CHARLES XIV JOHN OF SWEDEN

Getty

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte was born the son of a French lawyer in 1763, but died as King of Sweden—mostly because he was a nice guy. Bernadotte had a lengthy military career and turbulent relationship with Napoleon that saw him leading military campaigns through Germany and Italy. While there, he kept a handle on his troops, refusing to allow looting and theft, which gained Bernadotte respect from his adversaries, though later unsuccessful battles in Bernadotte’s career led to distrust from Parisian politicians in the early 1800s. In 1810, an ill and childless King Charles XIII led Sweden to conduct a star-search of sorts for an heir, and Bernadotte was offered the role of Sweden’s crown prince. Bernadotte was selected because of his military experience, but also due to the kindness and restraint he showed to Swedish solders during his military campaigns. Bernadotte adopted the name Charles XIV John and led Sweden following Charles XIII’s death in 1818 until his own death in 1844.

7. LEONARD THOMPSON

In 1922, doctors took a risk to save 14-year-old Leonard Thompson’s life by injecting him with an experimental substance: insulin. The young diabetic only weighed 65 pounds due to a starvation diet (the only treatment for diabetes at the time), and he was falling in and out of a coma. His parents were desperate for a solution, and though insulin was experimental and had not yet been tested on humans, they took a leap of faith and let the doctors inject Thompson with the mysterious drug. The first round of injections caused an allergic reaction in the boy, but after 12 days of tinkering, a purer insulin was extracted. Thompson's recovery was immediate, and within a month, front-pages were touting the new miracle drug.

8. GEORGE WASHINGTON

Getty

Washington’s famous Delaware River crossing helped win the Revolutionary War, but it could have—and really, should have—been foiled. On Christmas evening 1776, Washington moved 5400 men across the river as a surprise maneuver against Hessian troops. The strategy worked, but it shouldn’t have been a surprise at all because the Hessians had advance warning. Two Patriot deserters warned Hessian commander Col. Johann Rall the day prior about an imminent river crossing, but he dismissed the report as unlikely, probably due to countless false alarms. What’s more, a red coat spy in Washington’s camp passed along word of the attack, but again, Rall believed that if Patriot troops really did make an attempt, they would be easily fought off. Luckily for Washington, history shows it didn’t work out like Rall thought it would.

9. CONSTANTIN FAHLBERG

Chemist Constantin Fahlberg secured himself a sweet spot in history, all by accident. While Fahlberg takes much of the credit (and took much of the profit) for creating artificial sweeteners, he wasn’t the first scientist to discover saccharin. But, he was the first chemist to realize that saccharin was a sweet and edible chemistry accident that could be used in place of sugar. Legend has it that after working in his lab, Fahlberg ate a roll, which tasted sweet because of saccharin residue on his hand. He rushed back to his lab to taste-test all of his instruments—the beakers and vials, etc.—until he could determine where the sweetness came from. Soon after his discovery, Fahlberg cut out his lab partner and filed patents for a mass-produced artificial sweetener that would go on to change the food industry.

10. HARRISON FORD

Hollywood legend Harrison Ford landed a lifetime of a luck during his younger years that spurred his acting career. Ford had an acting contract with Columbia and Universal studios, but he was primarily working as a carpenter. "I had helped George Lucas audition other actors for the principal parts, and with no expectation or indication that I might be considered for the part of Han," Ford said during a Reddit AMA (though he also had a part in Lucas's American Graffiti four years earlier). "I was quite surprised when I was offered the part." Lucas was impressed though, and the part effectively launched Ford's career.

11. JOAN GINTHER

Joan Ginther, a Texas mathematician living in Las Vegas, is often called the “luckiest woman in the world” because she’s won multimillion dollar jackpots not once or twice—but four times. Ginther’s wins have all taken place in her home state and raked in $20 million between 1993 and 2010. But because of Ginther’s background in statistics (she has a PhD from Stanford), there’s speculation that she’s not lucky at all, but rather knows how to play the odds just right.

12. CHARLES LINDBERGH

Getty

They called him "Lucky Lindy" for a reason! Aviator Charles Lindbergh is best known for his solo transatlantic flight in 1927, but while Lindberg’s iconic trip was successful, his piloting history before that flight included four crashes: two in 1924 and two in 1926. He safely parachuted from each plummeting plane and went on to credit just how important a working chute was. “There is a saying in the service about the parachute: ‘If you need it and haven’t got it, you’ll never need it again!’ That just about sums up its value to aviation,” he wrote.

13. ROBERT BOGUCKI

American tourist and former Alaskan firefighter Robert Bogucki became the subject of a manhunt when he disappeared into Western Australia’s Great Sandy Desert in July 1999. By the time the second search team found him (the first had been called off over two weeks before), Bogucki had spent 43 days wandering nearly 250 miles through the desert, eating plants and drinking collected groundwater. Upon his discovery, Bogucki told his rescuers he was ready to go home: “Yeah, well. Enough of this walking around.” Bogucki said he wasn’t quite sure why he ventured off into the desert (where wintertime temperatures often reach upward of 90 degrees—quite a departure from the Alaskan weather he was used to), but thought it might have been to placate his spiritual needs. “I do feel satisfied I scratched that itch, whatever it was,” he told reporters. For whatever reason, Bogucki sure got lucky.