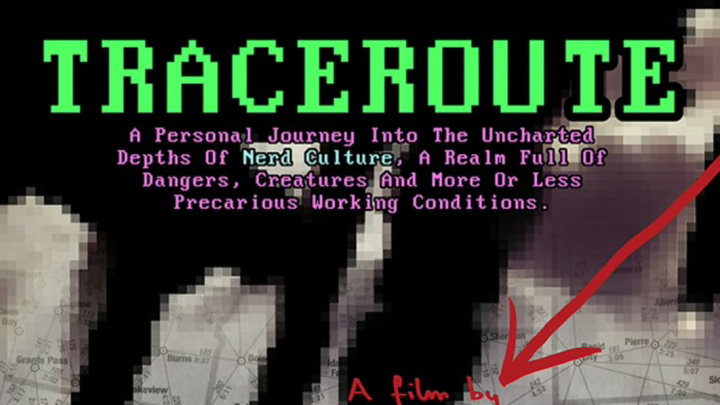

The documentary Traceroute screened last week in New York City, and is on the road now at film festivals. Director Johannes Grenzfurthner encourages fellow nerds to email him to request a screening. Here's a trailer:

Below, my review and a Q&A with the director.

A DOCUMENTARY ABOUT NERD CULTURE, VIA DELIGHTFUL NERDS

So here's the thing: This is a documentary nominally about "nerd culture," but it's actually good. As many nerds have noticed, there's a glut of nerd-positive documentaries out there, but they tend to be either too self-serious, or too focused on the trappings of fandom to actually say much.

Traceroute manages to be a real film, with humor and true insight (sometimes called out for us—and delightfully nullified—with a blinking "INSIGHT" faux-HTML tag onscreen), primarily because it focuses on Grenzfurthner's personal journey, and he doesn't take himself too seriously. Let's put that another way: The director uses himself and a handful of subjects to create his story, and that specificity—coupled with his playfulness—makes it work. At one point he licks the chrome head of a Terminator prop. Then he licks a zombie head prop. Then he licks the propmaster himself. It's delightful.

The film includes visits to Area 51, Stan Winston Studios, the parking lot at JPL, and a surprising array of other notable spots. It even has a lengthy segment shot at the place where Carl Sagan filmed the opening to Cosmos—the bit where he blew on a dandelion. There is a delight to seeing all of this, and how Grenzfurthner strings it all together. Sometimes it makes sense; sometimes it doesn't. Such is life on the road.

Born in Austria, Grenzfurthner made the film to mark his 40th birthday in 2015. It's a road trip from the West Coast of the US to the East, with many stops along the way to visit all sorts of nerds—from sex-toy designers to special effects designers to synthetic biologists to mechanics to CB radio repairmen to digital archivists. It's framed by near-continuous narration by Grenzfurthner, creating a dreamy feel, as we engage in his obsession with Sagan's Cosmos, a surprising number of Subway franchises, and a consistent theme of Grenzfurthner's anxiety about nuclear annihilation (he is a child of the Cold War, after all). Coupled with unusual camera work, occasional (intentional) glitching of the film, and a playful interaction of narrator with onscreen action, this film is a winner.

THE PHYSICALLY IMPOSSIBLE PROMISE OF "UNLIMITED BREADSTICKS"

Here's a representative quote from the middle of the movie, after a visit to the, ahem, adult toy makers Bad Dragon. Here:

[SCENE SHOWS THE CREW EATING AT OLIVE GARDEN, IN TIMELAPSE.] Grenzfurthner (voiceover): "Let's go to Olive Garden! It is a fascinating example of corporate culture. Its menu is entirely based on customer statistics. It offers as 'Italian food' what Americans think Italian food is. It's a gastro-empirical feedback loop, and it knocks us straight into a well-deserved alfredo coma." [TITLE: MARCH 12] [SCENE SHOWS ROILING CLOUDS IN THE SKY, AS GIANT METEORS BURN THROUGH THE ATMOSPHERE.] Grenzfurthner (voiceover): "What does my subconscious want to tell me? Maybe the physically impossible promise of 'unlimited breadsticks' haunts my skeptical mind. Or maybe it tells me that we should go to Flagstaff and check out Meteor Crater."

Moments later, we see Grenzfurthner completely alone, sitting on a park bench in front of a barren brick wall labeled "American Astronaut Wall of Fame." Seconds after that, he locates a Subway franchise and eats alone under a leafless tree in the desert. Then he wanders by Meteor Crater, more interested in eating his cookie than the crater. Then he stares at an air-conditioning unit. Then he notes a museum exhibit explaining meteor impacts using the "Impact" font; then a misspelling on a sign prohibiting "Arial" [sic] photography. The isolation and banality of these situations is truly funny, and also deeply nerdy. If you know what Impact and Arial are, it's a deep set of jokes. Even if you don't, it's still fun and accessible.

WHERE TO SEE TRACEROUTE

The film is still on the festival circuit, so it's not available online. When I asked Grenzfurthner how readers could check out this film, he suggested that they email him to arrange a screening, or visit one of the many screenings already lined up (scroll down past all the laurels and awards). One content note: While the film isn't rated, it does have a meaningful dose of sexuality and occasional salty language; I'd recommend leaving the kids at home for this one. (Better yet, have them figure out for themselves how to sneak into a screening.)

Q&A WITH THE DIRECTOR

Higgins:Many generations experience technological shifts. Yours (and mine) is the first to grow up in a world with disconnected computers in the home, then increasingly connected ones. We were also the first to grow up with some access to video cameras that used cheap tape, opening up a major avenue for filmmaking——cheap enough that even children could do it. From the documentary, it'€™s clear that computers have been a huge thing for you, but can you give me some background on your interest in filmmaking across the past 40 years? Seeing your (many) home movies in the early section of the film, clearly you were using that technology as well.

Grenzfurthner:

Yes, absolutely.

Historically speaking, the first wave of the punk/new wave (approximately 1976-1983) was primarily a movement of creative abuse of hardly-ever-used consumer media technology. Parents (usually technophile Baby boomer dads) bought expensive equipment like 8-track recorders, Super-8 and Polaroid cameras and later VHS camcorders and only used it to "document" birthday parties and other eminently boring ceremonies. But the rebellious teens found interesting new things to do with the dust-collecting media tech, and it started one of the biggest DIY revolutions of the 20th century. So punk (years before cyperpunk) was a movement of youngsters goofing around with (aka appropriating) consumer tech.

I was born 1975 and therefore too young to be an active part of the first punk/new wave movement, but you could say I was absorbing the second phase (1982-1988) as a kid through popular media. The damage was already done, because the aesthetics of new wave became mainstream, and I sucked it up like a sponge. In the long run, it brought me into the caring arms of Mondo 2000, Burroughs, RE/Search, you name it.

I was a very classic kid of the 1980s. Obsessed with watching TV. First there wasn't a big difference for me between an episode of Tom & Jerry and a re-run of Peter Hyams' Capricorn One. But that changed fast. I recorded it all on VHS, watched it over and over again and I began to understand how movies were carefully constructed emotional machines. I wanted to try to create them myself and so I wrote down stories. And our family camcorder was a neat tool to play with. The challenges of tech were frustrating and rewarding at the same time. An example: We didn't have two VCRs, so I always had to edit the video while shooting. If a take, let's say, of our Space-Shuttle-on-strings-movies was bad, I had to rewinded the tape and record the take again, overwrite the bad take. That always created these magical bursts of interference and micro-fragments between scenes, because the rewind function just wasn't precise enough. I'm still in love with these unwanted visual leftovers. During the editing of Traceroute I digitized many of the films I shot as a kid—and I wasted hours analyzing them frame-by-frame. Fascinating. Material semantics, hell yeah!

Filmmaking was something that I always returned to, and for me it is one of the most fulfilling arenas of creative problem-solving and teamwork. You constantly have to face difficulties: logistics, equipment, social drama, storytelling, acting. The emotional machine needs to be well tuned, and sometimes even hit with a sledge hammer, like a stereotypical Russian on a stereotypical MIR.

Higgins: Do you think there'€™s a meaningful distinction between the term '€œgeek'€ and '€œnerd'€? (And/or do you care?)

Grenzfurthner: I never wanted to get in this debate, because it doesn't really get us anywhere. It's like arguing if a specific color is called "ochre" or rather "salmon". If you want to be anal about colors, use the goddamn Pantone scale.

The term "nerd" represents a specific set of stereotypes and connotations—and for me it was important to talk to interesting people why they identify with it. It wasn't necessary to get into etymological details, but into personal stories. I would see Traceroute as a harsh exorcism ritual (including a lot of pea-soup-puking), but also a kind and loving embrace. It is a film about the deficits and wonders of obsession. It's about the guts of trauma, joy, and—ultimately—cognitive capitalism.

Higgins: In many of your interviews, I see a Flip camera positioned either in your hand, pointed back at the crew, or above you pointed down, or in other fairly unconventional places. And then you sometimes actually use that footage! What led you to make this unusual choice of camera placement?

Grenzfurthner: I like experimenting with form without being too masturbatory about it. Just trying to keep it interesting, flowing.

Traceroute's style reminds me of cut-up fanzines, ANSI art, BBS typesets, and is very collage-y. It made sense to also play around with our camera placements. In the editing process I ended up using that material quite a bit. I made sense. It was a very personal journey with two friends, but at the same time we created a film. So I wanted to make the making-of part of the final product. The journey was the reward, but also, in a very McLuhan way (that damned Catholic!), the message.

Higgins: You licked the Terminator and a zombie head. Do you recall what they tasted like?

Grenzfurthner: Like the bitter taste of history.

[All images courtesy of Monochrom/Johannes Grenzfurthner.]