Speech disorders—like stuttering—are most often treated with behavioral therapy, though a number of potential physical causes have been identified. Some studies have suggested that stuttering may be genetic, and new research appears to support that argument. A report published in the journal Current Biology details a recent study where young mice bred to carry a specific human gene mutation were shown to be more prone to stuttering.

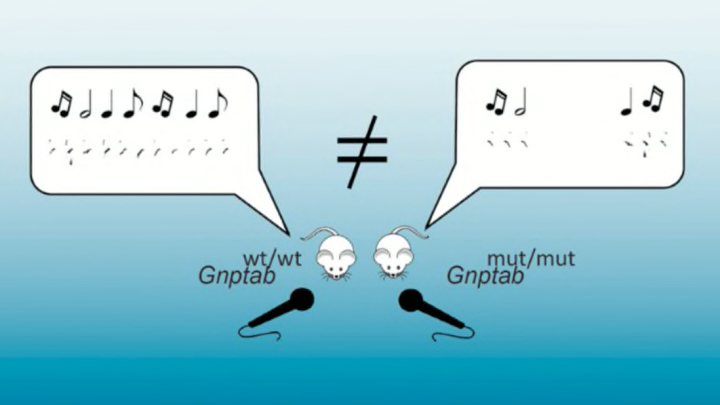

In 2010, researchers found that a mutation in the N-acetylglucosamine-1-phosphate transferase gene (Gnptab) is relatively common in people who stutter, but it's nowhere to be found in people with normal speech patterns. To further investigate whether the mutation actually causes stuttering, a different group of researchers bred the mutation into a generation of laboratory mice.

Many people believe that stuttering is a psychological or emotional problem. In order to eliminate the possibility that their test subjects might be experiencing distress or other issues, the researchers ran the mice through a series of tests. They evaluated the rodents’ motor skills, startle reflexes, sociability, willingness to explore, sense of smell, anxiety, and fear [PDF].

Young mice separated from their families make distress calls known as isolation cries. The researchers took one mouse at a time away from its mother and placed it in a cage designed for sound recording on the other side of the room. When the recording finished, the scientists would weigh the mouse, give it an identifying mark, and snip a little piece of tissue from its tail before returning it to its mother. Later, they tested the tissue samples to determine which mice were carrying the mutated gene.

The hypothesis was confirmed: mice without the mutation seemed to vocalize without trouble. Mice with the mutation, on the other hand, sounded like this:

Audio recording:Barnes et al./Current Biology 2016

Stuttering mice don’t make the same noises as stuttering humans, of course, but when the researchers compared their study subjects’ cries with recordings of people who stuttered, they found similar patterns.

"Many aspects of the vocalizations of our mice with the mutation are normal," researcher Tierra Barnes said in a press statement. "Where they differ is in the timing and temporal sequencing of their vocalizations. Their vocalizations have longer pauses than those of their littermates without the mutation, and there is evidence for more stereotyped repetitions in their vocalizations. These are very similar in some ways to the stuttered speech of humans who carry the same mutation.”

"Stuttering imposes an enormous burden on those that are severely afflicted with the disorder, yet its underlying causes have been very poorly understood," said co-author Dennis Drayna. "While it's surprising that the disorder can, to some degree, be recreated in a mouse, having an experimentally tractable animal model for some aspects of this disorder presents many exciting, new opportunities to move research in this area forward."