Scientists say people infected with parasitic worms may be better able to fend off autoimmune conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Their study shows that the infection changes the balance of bacteria in a person’s gut, overpowering the species that cause inflammation. The findings were published last week in the journal Science.

In many ways, human beings are healthier than we’ve ever been before. In other ways … not so much. The lifespan of the average American is longer than ever, but that long life is also more likely to be marked with chronic illness. Among medical conditions on the rise are autoimmune diseases like allergies, type one diabetes, and IBD. Scientists have theorized that the increase in autoimmune diseases may be influenced by our relatively sterile way of life. This hygiene hypothesis, as it’s known, posits that some exposure to germs is good for our immune systems. Without this exposure, our immune systems essentially short-circuit, leaving us vulnerable.

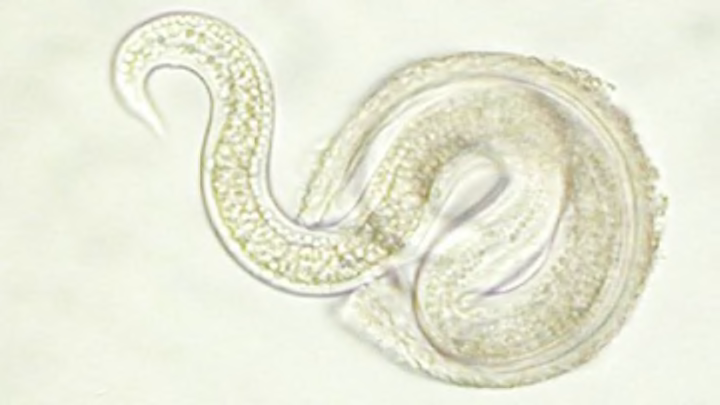

If hand sanitizer and antibiotics are the problem, some people say that worms may be the answer. Experiments have found helminth therapy (as it's called) may help celiac disease, multiple sclerosis, and Crohn’s disease, a form of IBD. Still, researchers have been cautious. “Nobody got hurt, nobody’s eyes fell out,” gastroenterologist Joel Weinstock told Science News in 2014. “But it’s still too early to say, ‘Well golly gee, this is going to be better than apple pie.’”

Apple pie or no, some Americans with chronic conditions can’t stand to wait, and are already intentionally infecting themselves with worms. One man found the treatment so effective that he felt he had to alert parasitologist P’ng Loke.

“I was contacted by an individual who had deliberately infected himself with worms to treat his symptoms of IBD and was able to put his disease into remission,” Loke said in a recorded interview. Loke and his colleagues wondered what, exactly, the worms were doing and how it could be helpful. They suspected that the infection might cause a person’s gut bacteria to re-balance, thereby overpowering the Bacteroides, a genus of “bad” bacteria that can lead to bowel inflammation.

The researchers bred mice that would carry a gene associated with immune conditions, including IBD. They then infected the mice with juvenile whipworms. After the worms had matured, the scientists took bacteria samples from the rodents’ poop and intestines. Sure enough, they found decreased levels of Bacteriodes and increased levels of Clostridia—a species that can reduce inflammation. Helminth infection had swung the bacterial balance in a more constructive direction.

To be sure that these effects were not just a mouse thing, the researchers also tested the gut bacteria of two groups of people in Malaysia: people from a rural area known for having low rates of IBD and high rates of worm infection, and people from a nearby city, for whom the IBD/worm situation was reversed. Once again, the results revealed that the immune response triggered by worm infection seemed to defend the bacterial ecosystem against Bacteroides inflammation.

“Patient testimonials and anecdotes lead many to think that worms directly cure IBD,” senior investigator Ken Caldwell said in a press statement, “while in reality, they act on the gut bacteria thought to cause the disease.”

Caldwell and his colleagues believe their findings offer a concrete explanation that may help lead to relief for patients. “Our study could change how scientists and physicians think about treating IBD.”