Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 232nd installment in the series.

APRIL 15, 1916: RUSSIANS CAPTURE TRABZON

While Russia’s main spring offensive on the Eastern Front failed at the Battle of Lake Naroch from March 18-30, 1916, Russian arms won great victories further afield in the opening months of 1916, most notably on the Caucasian Front. After a breakthrough at Köprüköy in January, Russian troops captured the ancient and strategically sited city of Erzurum in February, and then continued to advance west into the Turkish heartland of central Anatolia.

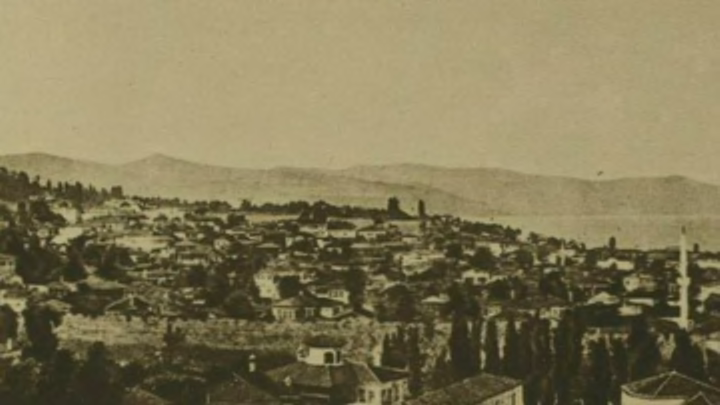

On April 15, 1916 the Russians delivered another discouraging setback to the Ottoman Empire with the occupation of Trabzon, another ancient city with both symbolic and strategic importance, abandoned without a fight by the outnumbered Turks. Originally founded in 756 BCE by Greek colonists from the nearby port of Sinope, Trapezous was known to the Romans as Trebizond and during the decline of the Byzantine Empire became the seat of its own empire from the 13th-15th centuries.

Click to enlarge

In the context of the First World War, its location on the north coast of Anatolia would allow the Russians to begin delivering supplies to the Caucasian Army partly by sea, avoiding the circuitous and time-consuming journey over the incredibly primitive terrain of the Caucasus and eastern Anatolia, with few roads and these mostly unfinished. It also boosted Allied morale and cemented Russian claims to territory in Asia Minor ahead of the long-expected breakup of the Ottoman Empire (now being negotiated by Allied diplomats in what would become the Sykes-Picot Agreement).

As in other recently conquered territories in Anatolia, the advancing Russians were shocked to find the region’s once-thriving Armenian Christian population had been more or less wiped out. Trabzon had been home to roughly 30,000 Armenians before the war, all of whom were massacred or deported during the ongoing Armenian genocide, including thousands herded out into the water or dumped from boats and drowned in the Black Sea at Trabzon.

The anonymous author of “The Russian Diary of an Englishman in Petrograd,” believed to be the diplomatic courier Albert Stopford, noted reports that the Turks were targeting many other minorities besides Armenians, including Christian Greeks and Assyrians: “When the Russians got to Erzrum there was not one Christian alive save six girls in the American Consulate. The guide of the Tiflis Hotel was a Christian Turk, not Armenian and his town was a little to the south of Erzrum. There all the Christians were also massacred – 840, including his old grandmother.”

Meanwhile diplomatic documents from the Ottoman Empire’s own ally, Imperial Germany, confirmed that the genocide was still in full swing in the spring of 1916 and left little doubt that it was officially sanctioned. The German ambassador to Constantinople, Wolff-Metternich, wrote to the Imperial chancellor Bethmann Hollweg on March 27, 1916: “Despite all the assurances to the contrary, the Porte is apparently beginning to decimate the remainder of the deported and, if possible, to exterminate those who have escaped the misery and the disaster before peace is made.”

Click to enlarge

On April 1, 1916, Ernst Jacob Christoffel, the head of a German charity for the blind in Malatya, left an even more detailed report of his personal observations in a letter to the German embassy in Constantinople:

Not a single Armenian sound is to be heard anywhere. Thousands were killed in Gemerek. In the area surrounding Yozgad, the population from 6 Armenian villages was massacred, all of them, even the infants… There were 500 men in a village near Sivas with which I have good relations; 30 of them are still alive. A family of 18 lost 14 of its members through sickness and murder. Out of other large families, one or 2 members are still alive. There are not isolated cases, but rather the rule. The number of those killed may be inferred from this.

Armenians who managed to survive the death marches then had to endure conditions in “concentration camps” that were in fact death camps, left to die in the desert with no food, no medicine, and no shelter. Often the process was hurried along by raids by itinerant neighbors looking to steal any remaining possessions or kidnap and rape Armenian women. April 6, 1916, Ernst Rössler, the German consul in Aleppo, wrote in a letter to the embassy in Constantinople: “During the past few days, the Armenian concentration camp in Ras-ul-Ain was attacked by the Circassians and other similar people living nearby. The largest part of the unarmed 14,000 inmates was massacred. There are no further details at this point; I will be informed of them later.”

On April 27 Rössler noted independent reports from Muslim Arabs serving in a labor corps, shocked at their first encounters with the genocide:

As the building of two bridges proved to be necessary… the 4th Army delivered a Syrian Muslim pioneer battalion for this purpose about 15 April. These people, who were transported in two days from Damascus to Ras-ul-Ain and who did not know anything about the plight of the deported Armenians and, as it can be presumed, were not influenced along the way, were quite horrified upon their arrival. They were of the opinion that the Armenians had been massacred by soldiers. This again demonstrates the common belief that the act had been done under orders. In any case, this was the opinion generally widespread in the area.

ESCADRILLE LAFAYETTE FORMED

Over two thousand miles to the west, on April 16, 1916 France celebrated one of the biggest symbolic demonstrations of unofficial American support yet, with the formation of the Escadrille Lafayette or “Lafayette Squadron,” an all-volunteer force of American pilots who joined this independent unit to help roll back German air superiority on the Western Front.

Originally known as the Escadrille Américaine (the name was changed in December 1916 under diplomatic pressure from Germany), the Escadrille Lafayette was actually one of two American volunteer squadrons that served in France, later augmented by the Lafayette Flying Corps (below, American pilots in the Escadrille). Both were composed mostly of young, upper-class American college men with the means to travel to France and support themselves during a long leave of absence from schools like Harvard and Princeton.

Wikimedia Commons// Public Domain

The Escadrille Lafayette was founded by a handful of colorful characters, as reflected in their decision to adopt a lion cub called “Whiskey” as the Escadrille’s mascot, who traveled with them wherever they served (or went on leave). One of the early volunteer flyers, James McConnell, remembered some of the difficulties associated with transporting Whiskey during leave in Paris:

The little chap had been born on a boat crossing from Africa and was advertised for sale in France. Some of the American pilots chipped in and bought him. He was a cute, bright-eyed baby lion who tried to roar in a most threatening manner but who was blissfully content the moment one gave him one's finger to suck… Lions, it developed, were not allowed in passenger coaches. The conductor was assured that “Whiskey” was quite harmless and was going to overlook the rules when the cub began to roar and tried to get at the railwayman's finger. That settled it, so two of the men had to stay behind in order to crate up "Whiskey" and take him along the next day.

The Escadrille Lafayette went into action almost immediately at Verdun, taking to the air for the first time as a combat unit on April 20, followed by its first kill on April 24. With their birds’ eye view of the action, its pilots also played an important role observing and reporting enemy troop movements and artillery positions. They also gained a rare aerial perspective on the incredible destruction wrought by modern warfare. On May 23, 1916, volunteer pilot Victor David Chapman described the scene at Verdun from the air:

The landscape – one wasted surface of brown powdered earth, where hills, valleys, forest and villages all merged in phantoms – was boiling with puffs of dark smoke. Even above my engine’s roar I could catch reports now and then. To the rear, on either side, tine sparks like flashed of a mirror, hither and yon, in the woods and dales, denoted the heavy guns which were raising such a dust… Even from above, one had the sense of great activity and force in the country to the rear. From every wood and hedge peeped out “parcs” of autos, wagons, tents and shelters, – while all the roadsides showed white and dusty with the ceaseless travel.

McConnell left a similar description of Verdun seen from the air:

Now there is only that sinister brown belt, a strip of murdered Nature. It seems to belong to another world. Every sign of humanity has been swept away. The woods and roads have vanished like chalk wiped from a blackboard; of the villages nothing remains but gray smears where stone walls have tumbled together. The great forts of Douaumont and Vaux are outlined faintly, like the tracings of a finger in wet sand. One cannot distinguish any one shell crater, as one can on the pockmarked fields on either side. On the brown band the indentations are so closely interlocked that they blend into a confused mass of troubled earth. Of the trenches only broken, half-obliterated links are visible.

Pilots also had a front-row seat for artillery bombardments, as many claimed they could actually see the shells hurtling through the air. McConnell described the strange, alarming feeling of flying through a fusillade:

Columns of muddy smoke spurt up continually as high explosives tear deeper into this ulcered area. During heavy bombardment and attacks I have seen shells falling like rain… A smoky pall covers the sector under fire, rising so high that at a height of 1,000 feet one is enveloped in its mist-like fumes. Now and then monster projectiles hurtling through the air close by leave one’s plane rocking violently in their wake. Airplanes have been cut in two by them.

See the previous installment or all entries.