Patrick Henry, the American patriot born on May 29, 1736, is best remembered for saying “Give me liberty or give me death” during a speech to the Second Virginia Convention on March 23, 1775, though he might not have actually ever said those words. Whether that famous quote was his or someone else’s, Henry’s importance to the republic that he helped found cannot be denied. Here are 10 facts about him.

1. Patrick Henry’s father was an immigrant.

A native of Aberdeen, Scotland, John Henry hailed from a relatively affluent, well-regarded family. His intelligence and Latin composition skills helped earn him a scholarship. Also enrolled at the school was John Syme, a childhood friend, who had made his fortune in Virginia. Henry decided to join him. In 1727, John Henry set sail for the colony, where he worked with Syme.

Henry acquired over 15,000 acres of land in his first four years in Virginia. In 1731, Syme passed away, and two years later, Henry and Syme’s widow Sarah were married. They went on to have 11 children, nine of whom survived. One of them was Patrick Henry.

2. Patrick Henry played several musical instruments.

Patrick Henry lived at Studley—the family farm in Hanover County, Virginia—until he was 14 years old. He pursued several hobbies, including hunting (he was, one associate said, “remarkably fond of his gun”) and playing the flute and violin. As an adult, he loved comedic novels, especially The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, a satire by Laurence Sterne.

3. He failed at tobacco farming.

Henry’s professional life began with a string of unsuccessful business ventures. In 1752, John Henry set up a shop for Patrick and his brother, William, to run on their own. It closed two years later.

Marriage inspired Patrick Henry to pursue a different career. In 1754, 18-year-old Patrick married his first wife, Sarah Shelton, whose dowry included a 300-acre farm. There, he grew wheat, barley, and tobacco, until the family house burned down in 1757. Henry then began working at his father-in-law’s tavern.

The Hanover County Courthouse was across the street from this establishment, and lawyers would congregate there after a day of arguing cases. Henry got to know them and developed an interest in law. He passed the bar exam at age 24 and set up a successful practice.

4. A legal case dubbed the “Parsons’ Cause” made him famous.

A three-year drought in the mid-1750s hurt Virginia’s tobacco farms, which produced the main driver of the colony’s economy. The crisis impacted everyone, including Anglican clergymen, who were typically paid in tobacco. Each minister usually received 16,000 pounds of the crop per year.

In 1755, the House of Burgesses (Virginia’s democratically elected legislative body) restructured this generous payment policy by passing the Two Penny Act. Under the new law, clergyman would instead be paid two pence in cash for every pound of the crop that he would be normally entitled to. Due to the market price of tobacco, though, the act amounted to a pay cut. King George II sided with ministers who were infuriated by the new scheme and vetoed the law in August 1759.

In 1763, Reverend James Maury (the parson of the “Parsons’ Cause”) sued his church for back pay. Patrick Henry represented the church and used the platform to denounce the king’s meddling in Virginia’s democratic government. “A king, by annulling or disallowing Laws of this salutary nature, from being the father of his people, denigrates into a tyrant,” he argued. Henry’s rhetoric turned him into a popular figure throughout Virginia.

5. The true authorship of Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty” address is unclear.

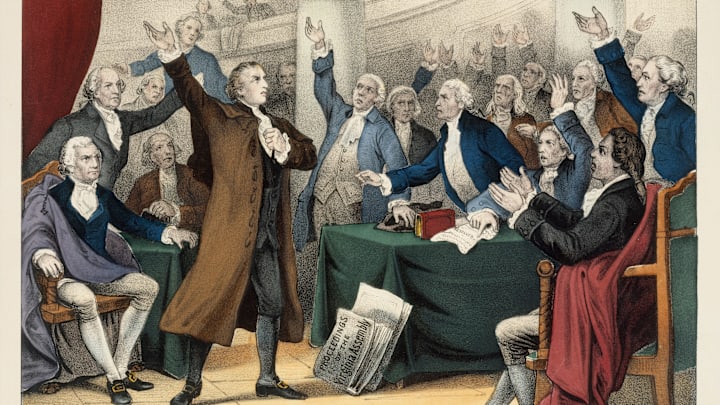

On March 23, 1775, Henry gave a speech that would capture the spirit of the American Revolution. Addressing the Second Virginia Revolutionary Convention in Richmond, he insisted that war with Britain was inevitable and argued that nothing less than an organized militia could defend the colonies.

Like all great orators, he saved his best line for last: “I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!”

But Henry may not have said this memorable quote. Nobody who heard the speech wrote a transcript of it. The text of the address was not published until 1817 in a biography of Henry by William Wirt, a future attorney general under James Monroe. To reconstruct the speech, Wirt interviewed eyewitnesses and pieced their recollections together. He said later that he used federal judge St. George Tucker’s description “almost entirely.”

Were all of those inspired words really Henry’s? If not, to what degree did Wirt or his interviewees embellish them? Most historians believe that the speech as recreated by Wirt is at least somewhat faithful to Henry’s original remarks. We’ll probably never know for certain.

6. Patrick Henry was the first elected governor of Virginia.

In 1776, he won the first of three consecutive gubernatorial terms, remaining in office until June 1, 1779. During this time, Henry married his second wife, Dorothea Dandridge. (Sarah Henry had died in 1775 after coping with mental illness for several years.) He was subsequently re-elected governor in 1784 and served another two years.

7. Patrick Henry argued unsuccessfully against the U.S. Constitution.

When Henry was offered the chance to participate in the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, he declined—and he went on become one of the Constitution’s loudest foes.

He feared its provisions leaned “towards monarchy,” giving too much power to the federal government. “The concern I feel on this account,” he told George Washington, “is really greater than I am able to express.”

Consequently, Henry spoke out against its adoption during the Virginia Ratification Convention in 1788. No one at the convention spoke at greater length on the subject—during the three-and-a-half-week event, Henry consumed nearly 25 percent of the total floor time. On June 25, Virginia’s representatives adopted the Constitution by a 10-vote margin.

8. He was an early advocate of the Bill of Rights.

When the Constitution was sent to Virginia for ratification in 1788, Henry wanted a bill of rights to be included, but most delegates, including James Madison, didn’t think one would be necessary. Henry thought its absence signaled a federal power grab.

Madison, struggling to convince Virginia’s anti-federalist delegates to ratify the Constitution, arranged for a bill of rights to be added once the Constitution was approved. The first U.S. Congress drew up a list of 12 rights and sent them to the states for ratification, but this wasn’t good enough for Henry. He vented his dissatisfaction to Virginia representative Richard Henry Lee, saying that unless the federal government’s size was decreased, the amendments would “tend to injure rather than serve the cause of liberty.” The states ended up approving 10 of the rights, which were amended to the Constitution in 1791.

9. Henry turned down George Washington’s attempt to appoint him secretary of state.

America’s first president offered Henry the position after his previous secretary of state, Edmund Randolph Jennings, resigned in 1795. Henry declined, telling Washington that “my domestic situation pleads strongly against a removal to Philadelphia,” America’s then-capital. Henry was supporting “no less than eight children by my present marriage,” and a widowed daughter from his previous one. Washington eventually appointed Federalist Timothy Pickering.

10. Henry’s political allegiance evolved over time.

Henry generally allied with the Jefferson-led Democratic-Republicans, but toward the end of his life, however, he softened his position against some Federalist policies and candidates. In 1799, Henry even ran for the Virginia state legislature as a member of Alexander Hamilton’s party.

On the campaign trail, he delivered what would be his last public speech at the Charlotte County, Virginia, courthouse. In a debate with Democratic-Republican John Randolph, Henry said that although the people had the right to overthrow the government, they should do so only when there was no other recourse; otherwise, the nation would descend into monarchy. “United we stand, divided we fall,” Henry said. “Let us not split into factions which must destroy that union upon which our existence hangs.”

He won the seat in the legislature, but died on June 6, 1799, before his first term began.

A version of this article was originally published in 2017 and has been updated for 2023.