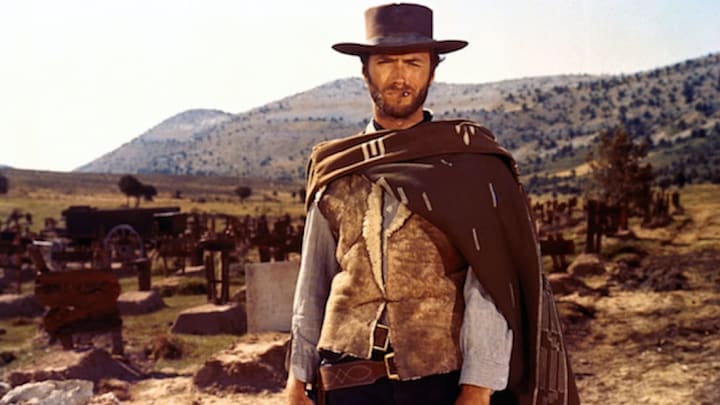

Though it has to forever compete with The Searchers and High Noon, few Western films will ever have the impact of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, the final film in Sergio Leone’s “Dollars Trilogy” and the most famous Spaghetti Western (that is, films in the American Western style made by Italian directors) of all time. It catapulted Clint Eastwood to super-stardom, changed the way countless directors thought about the genre, and continues to influence film to this day. Here are a dozen facts about the legendary tale of gunslingers on the hunt for treasure.

1. THE FILM’S STORY WAS IMPROVISED IN A MEETING.

In late 1965, A Fistful of Dollars and its sequel, For a Few Dollars More, were not yet available in the United States, but their success in Europe was not lost on American film executives. Hoping to capitalize on the buzz and secure a lucrative American distribution deal, director Sergio Leone and writer Luciano Vincenzoni brought Arthur Krim and Arnold Picker—two United Artists executives—to Rome, where they were treated to a screening of the second film at a massive cinema where For a Few Dollars More was playing to enthusiastic crowds.

The American executives were interested, and agreed to pay $900,000 for the American rights (a huge amount at the time, particular considering the fact that Eastwood was not yet the massive star he’d become), but as the principals gathered to sign the deal, Picker asked if Leone, Vicenzoni, and producer Alberto Grimaldi had thought about what they’d be doing next, as he was hoping for yet another Western to package with the first two films. The three men hadn’t thought about it before, but Vincenzoni thought quickly, and improvised an idea.

“I don’t know why, but the poster came into my mind—Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo. ‘The Good, The Bad and the Ugly,’” said Vincenzoni. “It’s the story of three bums that go around through the Civil War looking for money.”

Based on that short pitch, Picker agreed to fund the film, and the movie was on its way. Eventually, all three films were released in America over the course of a single year.

2. CLINT EASTWOOD’S SALARY DEMANDS DELAYED FILMING.

Eastwood initially agreed to return for a third film, but was disappointed when he read the script and discovered that he’d be sharing the screen with two other major players: Eli Wallach and Lee Van Cleef (who’d already co-starred with Eastwood in For a Few Dollars More). In Eastwood’s view, the increasing reliance on an ensemble was crowding him out of the movie.

“If it goes on this way, in the next one I will be starring with the American cavalry,” Eastwood reportedly said in response to the story.

Negotiations for the third film fell apart, and Eastwood’s agents and publicist worked hard to bring him back to the production. What’s most interesting about this was that, because the films still had not come out in America, Eastwood was not yet the huge star that we know him to be today, so he had less negotiating pull than you might expect. Still, his agents were ultimately able to get him a $250,000 salary for the film (more than the entire budget of A Fistful of Dollars), plus 10 percent of the profits when the film was finally released in America. As a cherry on top, he was also promised a new Ferrari. Of course, he ultimately accepted the job.

3. ELI WALLACH SAID YES AFTER SEEING ONLY MINUTES OF THE PREVIOUS FILMS.

For the role of Tuco, a.k.a. “The Bad,” Leone initially wanted Italian actor Gian Maria Volontè, who’d played villainous roles in both previous films. When Volontè turned the role down, Leone turned to American actor Eli Wallach, who was at the time best known for his role in The Magnificent Seven. Wallach was skeptical of making a Western with, of all people, an Italian director, but a screening was arranged in an attempt to convince him. After watching just minutes of one of the first two “Dollars” films, Wallach told the projectionist that he could turn the movie off, and accepted the job.

4. SERGIO LEONE DID NOT SPEAK ENGLISH, AND THUS COULD NOT SPEAK DIRECTLY TO EASTWOOD.

By the spring of 1966, Sergio Leone had made two films with Eastwood, one film with Van Cleef, and was about to make a third film along with another American actor: Eli Wallach. Despite this, Leone did not speak English, and relied on an interpreter. Wallach, however, was able to communicate with Leone in French, in which the director was fluent.

5. LEONE DID COPIOUS RESEARCH.

Because the film was set during the Civil War, Leone wanted to preserve a certain sense of accuracy, and went to America to research the film. Among his inspirations were Library of Congress documents and the photographs of legendary photographer Mathew Brady. The film is not completely historically accurate, though. It features the use of dynamite before that particular explosive was invented.

6. THE FAMOUS BRIDGE EXPLOSION HAD TO BE SHOT TWICE.

For the scene in which Blondie (Eastwood) and Tuco (Wallach) decide to blow up the bridge that leads to the cemetery where they believe the gold they seek is buried, the production hired hundreds of Spanish soldiers to stand in for Civil War fighters. The shoot was complicated. The soldiers all had to be in the right, safe place, and Leone set up several cameras to film the moment while waiting for the perfect light to capture it.

As Eastwood and Wallach watched from a nearby hilltop (where Eastwood apparently practiced his golf swing), Leone watched the sky, waiting for the right light. The signal to blow up the bridge was supposed to be the word “Vaya,” and the crew gave a Spanish officer the honor of igniting the blast. Unfortunately, a member of the crew, while trying to hurry a cameraman, said “Vaya” too quickly. The officer heard the word and blew up the bridge.

The special effects expert who accidentally triggered the explosion with his words fled the set quickly, while Leone simply said, “Let’s go eat.” The bridge was rebuilt, and the scene was re-shot, driving up the budget of the film.

7. EASTWOOD HATED HIS CIGARS.

Eastwood’s “Man With No Name” character is easily identified by the little cigarillos he’s almost constantly smoking. Unfortunately for Eastwood, he didn’t really have a taste for them, and Leone was a fan of multiple takes. So Eastwood had to smoke quite a bit, and sometimes he felt so bad that he had to lay down an ultimatum.

According to Wallach, Eastwood would sometimes tell the director: “You’d better get it this time, because I’m going to throw up.”

8. WALLACH WAS ALMOST SERIOUSLY INJURED THREE TIMES.

Of all the stars of the film, it seems Wallach had the hardest time while shooting. For the scene in which he’s about to be hanged while sitting atop a horse (the idea was that the horse would be ushered away, thus leaving him to hang), Eastwood was supposed to fire a rifle at the rope. A small explosive charge in the rope would then detonate, thus freeing Wallach. What Leone didn’t count on was that the horse would be spooked by the sound of the rifle, and take off at a dead gallop with Wallach on its back, his hands still tied.

“It took me a mile before that horse stopped,” Wallach recalled.

For the scene in which Tuco escapes Union captivity by cutting his handcuffs under a moving train, Leone wanted to make sure the audience saw Wallach himself, and not a stuntman, lying beside the train as it sped by. Wallach agreed, then realized after the first take that a metal step affixed to one of the cars had missed his head by inches.

“I realized that if I had raised my head four or five inches I’d be decapitated,” Wallach said.

His troubles still weren’t done, though. During the film’s climax, when Tuco unearths the gold hidden in the cemetery, the crew applied acid to one of the bags of gold, so that when Wallach hit it with his shovel it was guaranteed to split open on cue. What the crew didn’t tell Wallach was that they were keeping the acid in a bottle that once held a brand of lemon soda that he enjoyed. Wallach saw the bottle and, thinking it was his favorite drink, took a sip. Luckily, he realized his mistake before it was too late.

9. IT’S TECHNICALLY A PREQUEL.

Careful viewers of the “Dollars Trilogy” will note that, though it’s the final film, The Good, The Bad and The Ugly actually takes place prior to the other two films. Among the clues: Eastwood acquires his iconic poncho, worn in both A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More, in the final minutes.

10. “THE UGLY” AND “THE BAD” ARE REVERSED IN THE FIRST TRAILER.

In the final film, Tuco is designated as “The Ugly,” while Lee Van Cleef’s character, Angel Eyes, is “The Bad.” In the original trailer for the American release, though, Angel Eyes is “The Ugly” and Tuco is “The Bad.”

11. EASTWOOD TURNED DOWN A FOURTH FILM.

By the end of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, Eastwood was done working with Leone—a famous perfectionist—and had resolved that he would form his own company and start making his own movies. Leone, on the other hand, wasn’t necessarily done with Eastwood. He even flew to Los Angeles to pitch him the role of “Harmonica” (ultimately played by Charles Bronson) in Once Upon a Time in the West. Eastwood wasn’t interested.

12. JOHN WAYNE WAS NOT A FAN OF EASTWOOD.

Before Leone’s Westerns hit America, heroic gunfighters were almost always portrayed as men who waited for the villain to draw their guns first, the idea being that these were men who wouldn’t kill unless they had to. Among these heroes was John Wayne, whose career was winding down just as Eastwood’s was heating up. According to Eastwood, director Don Siegel (who made several films with Eastwood, including ) once tried to get Wayne to be more like the “Dollars Trilogy” star during the filming of Wayne’s final film, The Shootist. Wayne, it turns out, was not a fan of Eastwood’s more ruthless Western style.

For a scene in The Shootist in which Wayne was originally supposed to sneak up behind a man and shoot him in the back, Wayne declared “I don’t shoot anyone in the back.”

Siegel, according to Eastwood, replied: “Clint Eastwood would’ve shot him in the back.”

Wayne’s response: “I don’t care what that kid would’ve done.”

Additional Sources:

(2004)

by Patrick McGilligan (1999)

by Marc Eliot (2009)

Inside The Actors Studio: “Clint Eastwood” (2003)