This week the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it has no authority to decide cases that challenge partisan gerrymandering—a practice in which political parties draw Congressional districts to increase votes in their favor. Gerrymandering shifts power away from voters to toward the parties, and the Supreme Court's decision is likely to increase the momentum.

But how, exactly, do elected officials pick and choose their voters? Their main tactic is as simple as it is unfair. By redrawing the borders of electoral districts, members of a given political party can cram the opposition’s supporters into as few precincts as possible—thus grabbing a disproportionate amount of power.

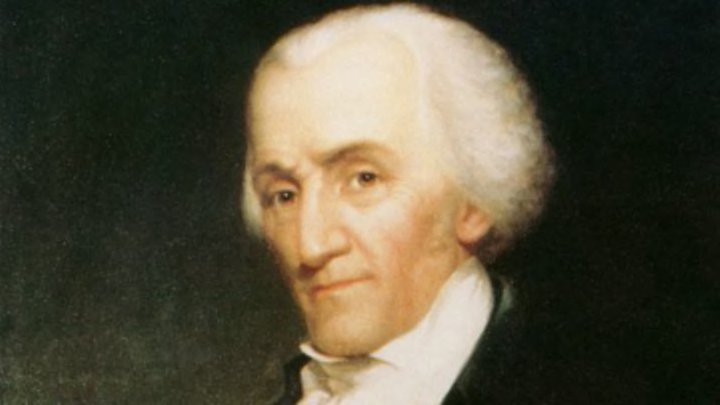

The tactic gets its name after a man who helped make the Bill of Rights happen, a one-time vice president, and the only signer of the Declaration of Independence who's buried in Washington, D.C.

“A Man of Immense Worth”

Elbridge Gerry was born on July 17, 1744. He was a native of Marblehead, Massachusetts, and both his parents were linked to the merchant business. Gerry took up the trade in 1762 and became an exporter of cod (a profitable fish upon which countless fortunes have been built).

At age 28, he won a seat on the colony’s general court, where he’d come to share Samuel Adams’s revolutionary rhetoric. In 1776, Gerry joined the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Throughout his tenure there, Gerry demanded pay raises for patriot troops, earning him the nickname “soldier’s friend.” The merchant’s integrity was widely admired, even by John Adams (who was notoriously hard to impress). “[He] is a man of immense worth,” wrote the future president. “If every man here was a Gerry, the liberties of America would be safe against the gates of Earth and Hell.”

In 1787, with the war over, Gerry took part in the Constitutional Convention. The importance of his presence cannot be understated. After all, it was he who moved to include a Bill of Rights—an idea that his colleagues shot down. Five days after the proposal, the newly completed Constitution was ready to be signed. Since a Bill of Rights was nowhere to be found, Gerry—along with just two other delegates who made it to the end of the convention—withheld his signature.

A subsequent letter to the Massachusetts State Legislature explained this choice. “It was painful for me, on a subject of such national importance, to differ from the respectable members who signed the Constitution; but conceiving, as I did, that the liberties of America were not secured by the system, it was my duty to oppose it,” Gerry stated. He may have lost that battle, but he ultimately won the war. Thanks in part to dissenters like him, a 10-amendment Bill of Rights was formally adopted on December 15, 1791.

Had he retired from politics right then and there, Elbridge Gerry might have gone down in history as the “Father of the Bill of Rights.” Instead, he’s remembered first and foremost for another, less admirable claim to fame.

Redrawing his legacy

Massachusetts made Gerry its eighth governor in 1810. By then, America had turned into a nation divided. Two rival parties now split the electorate: Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans and the late Alexander Hamilton’s Federalists.

Gerry belonged to the former group, which backed his successful re-election campaign in 1811. At the time, Democratic-Republicans represented the Massachusetts legislature’s majority party. This gave them enough votes to pull off a rather devious scheme that secured big wins in the state Senate one year later.

The plan was brilliant in its straightforwardness. Early in 1812, Democratic-Republican legislators laid out new districts which shoehorned most Federalist Party supporters into a handful of precincts.

Behind closed doors, Governor Gerry denounced this plot, calling it “highly disagreeable.” Unfortunately, that didn’t stop him from signing the proposed new districts into law anyway. The result was a monstrously slanted election season. Overall, Federalist candidates for the state Senate earned 1602 more votes than their Jeffersonian opponents did. Yet, because of these new precincts, the Democratic-Republican Party nabbed 29 seats to the Federalist’s 11.

The new state electoral map looked positively absurd. Thanks to partisan manipulation, districts now came in all manner of irregular shapes. Particularly infamous was one such division in Essex County. To the staff of The Weekly Messenger, a prominent Federalist newspaper, this squiggly precinct looked like a mythical salamander. Thus, the name “Gerrymander” was born—and it stuck.

The Federalist surge meant that Gerry was ousted from office, but Gerry’s career wasn’t quite over yet. On the contrary, it saw a swift rebound when James Madison chose him to become his second vice president the following year. But like Madison’s previous VP, Gerry didn’t last long. Death took him while he was still in office on November 23, 1814.

Those interested may find his grave in the capital city of the nation he helped create. Nestled inside Washington’s Congressional Cemetery is Elbridge Gerry’s tomb. Above it sits the first monument ever funded in full by the federal government, where visitors can read Gerry’s personal creed: “It is the duty of every man, though he may have but one day to live, to devote that day to the good of his country.”