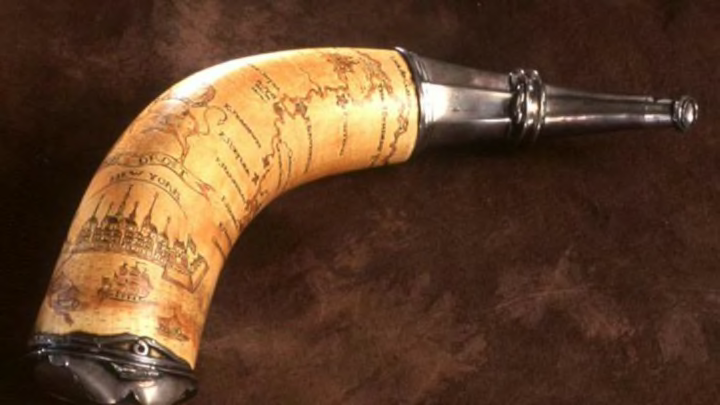

This powder horn, which likely dates to sometime between 1757 and 1760, is inscribed with a map of the Hudson and Mohawk river valleys. Details visible on the horn include Lakes Champlain and Ontario, smaller towns and forts, and decorative depictions of boats and houses. New York City, represented as a simple skyline with boats sailing on an open sea in the foreground, appears at the bottom of the horn.

This beautiful object is an example of one of many types of decorated powder horns made in the 18th and early 19th century to hold the gunpowder used to fire muskets. Men etched diary entries on them, or popular rhymes, or names of hometowns.

Did frontiersmen who carried a map horn like this along with their muskets put the information to use while moving through the rapidly-settling wilderness? The Library of Congress writes that this is possible, but “it is more likely that the map images provided records or mementos of the areas that the owners traversed” (or, in the case of military-themed horns, “campaign[s] in which they were involved”). This horn, then, may have been a souvenir rather than a guide.

In a 1945 book about the J. H. Grenville Gilbert collection of powder horns, which Gilbert donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1937, Stephen V. Grancsay writes that we have numerous surviving examples of horns depicting this particular area of the country. This is because at the time, “the rivers and lakes of this region … were open paths of both warfare and trade.” Horns with maps of other colonial regions—Massachusetts and Pennsylvania—are rarer.

American powder horns were usually made using horns from cows, bullocks, or oxen, selected for their beauty and size. If well-made and cared for—caulked around the wooden bottom plug with hemp or tallow; fitted with a precisely-carved wooden stopper—a horn was capable of keeping powder dry even under wet field conditions. Men wore them on a strap over their shoulders, so that they dangled at their sides.

Many who needed horns made them at home, but there was a trade in fancier specimens. Professionally made horns were often, Grancsay writes, “dipped in a yellow dye to give the surface the appearance of amber,” or scraped thin and then stained with butternut bark to bring out their translucence. Engravings could be punched up by using various locally available dyes, and the whole thing could be preserved with shellac. It seems possible that this horn may have benefited from one or more of these processes, since it’s still so beautifully legible.

Peter Force, a 19th-century politician and mayor of Washington, D.C. who was an avid and influential amateur archivist and accumulator of early Americana, collected this horn along with several others. The Library of Congress bought the group in 1867, along with the rest of Force’s vast collection; the Library now holds eight map horns total.