Following the success of Serial and The Jinx, in late 2015 Netflix released Making a Murderer, a documentary series that follows the at-times unbelievable story of Steven Avery, a now-56-year-old man from Manitowoc, Wisconsin who is currently in prison for a murder he may or may not have committed. It's a familiar scenario for Avery, who previously spent 18 years behind bars for a sexual assault he was wrongfully convicted of (DNA evidence freed him in 2003).

If you didn't binge-watch all 10 episodes of the highly addictive Netflix series as soon as it dropped, you'd better get started. Because after nearly three years of waiting, a second season just arrived with 10 all-new episodes that dive into Avery's life post-conviction, and his ongoing efforts to clear his name and be released from prison once again. Here are 17 compelling facts about the making of the docuseries.

1. THE PROJECT WAS INSPIRED BY A FRONT-PAGE ARTICLE IN THE NEW YORK TIMES.

In 2005, Making a Murderer co-creators Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi were both film students at Columbia University when a front-page story in The New York Times—“Freed by DNA, Now Charged in New Crime”—caught their attention.

“I found it riveting and kept elbowing poor Moira and saying, ‘I cannot believe this,’” Ricciardi told BuzzFeed. “The focus of that story was the backlash the Wisconsin Innocence Project was experiencing as a result of having been instrumental in freeing Steven. Of course, as it got deeper into the article, I realized that there was an apparent conflict of interest between the county and him.” As storytellers, they were immediately intrigued.

2. THE FILMMAKERS DIDN’T HAVE AN OPINION ON STEVEN AVERY’S GUILT OR INNOCENCE.

The question of Steven Avery’s guilt or innocence wasn’t what motivated the filmmakers. In fact, they told Vulture that it wasn’t a question they even considered. “When we first started we didn't have an opinion as to his guilt or innocence,” Ricciardi admitted. “What drew us to this story was Steven's status as an accused. In this country, people being accused of heinous crimes is unfortunately not that rare an event, but the fact that Steven had been wronged by the system, and was in the process of trying to reform the system and hold people accountable just raised so many questions. Could somebody who had those motivations possibly do something like this? Or did somebody trying to change the system see the system come back down on top of them? Either way, there was a story.”

3. BEFORE SHE WAS A FILMMAKER, LAURA RICCIARDI WAS A LAWYER.

As much as it’s a true crime documentary, Making a Murderer also operates as a forensic science procedural and courtroom drama, which made Ricciardi’s legal background extremely helpful in reviewing Avery’s case and how it was handled. Before pursuing her MFA in film at Columbia, Ricciardi earned a JD from New York Law School. Throughout the decade she and Demos worked on the first season of the series, Ricciardi helped pay the bills by continuing to work in the legal field.

4. THE FILMMAKERS MOVED FROM NEW YORK TO WISCONSIN TO IMMERSE THEMSELVES IN THE SUBJECT.

Within weeks of reading that original New York Times article, Demos and Ricciardi made their way to Wisconsin after learning that they were allowed to watch video from the courtroom and could dig further into the story. As they were getting ready to head back to New York, the police held a press conference, during which they announced that Avery’s nephew, Brendan Dassey, was officially being considered a suspect. “It caught everyone off guard,” recalled Demos. “At that point, we knew that this was going to be more than we had thought.”

The two decided that if they were going to pursue this story in earnest, they needed to relocate to Wisconsin. “Part of that was so we could be there for every court date and every development,” Ricciardi said, “but also so that we could start to reach out to subjects and do interviews about the past and go through archival materials.” They moved to Manitowoc in January 2006, and remained there for about a year and a half.

5. THE FIRST SEASON WAS PRODUCED OVER A 10-YEAR PERIOD.

The math is pretty easy on this one: Demos and Ricciardi began developing the project in 2005, and celebrated its debut on Netflix in December—meaning they invested a full 10 years of their lives in just the first season of the project.

6. IT WAS STEVEN AVERY WHO CONVINCED HIS FAMILY TO PARTICIPATE.

Over the course of the decade they worked on the film, the moviemakers “developed an amazing relationship with the Avery family,” according to Ricciardi. And they owe much of the access they were given to the Avery family to Steven directly. “We started to get to know Steven by telephone and we eventually started meeting him at the county jail, developing a relationship with him and gaining his trust,” Ricciardi told Vulture. “He called and arranged for Moira and me to go out and meet his mother. We were really impressed with how open the Averys were to meeting us. They heard us out about who we were and what we were doing and why we were interested in their story. It's very much Steven's story, but it's also a family's story. It's clear that when someone is wrongfully imprisoned, not only that person but all their loved ones endure it as well.”

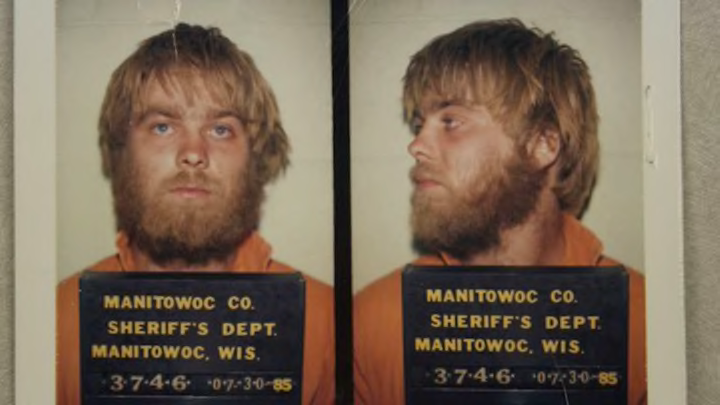

7. AVERY’S PAST BRUSHES WITH THE LAW WERE WHAT MADE HIM AN INTERESTING SUBJECT TO THE FILMMAKERS.

Netflix

Though critics of the series claim that the filmmakers did not give a detailed accounting of Avery’s criminal past, both Demos and Ricciardi have said that Avery’s flaws are what made him so interesting to them in the first place. “In some ways that’s part of the point,” Demos told BuzzFeed. “If you want to push him away at the start and by Episode 10, you care about him, you’ve grown as a person and that’s really important.”

8. THEY SHOT NEARLY 700 HOURS OF FOOTAGE.

According to The New York Times, Demos and Ricciardi “shot over 500 hours of interviews and visuals, then recorded another 180 hours at trials” throughout the 10 years of production.

9. THE FILMMAKERS BELIEVE THE STATE OF WISCONSIN WANTED TO BURY THE FILM.

Demos and Ricciardi made their presence—and their project—known while they were in Wisconsin, which purportedly didn’t sit well with the state. In 2006, the filmmakers were forced to hire a lawyer after the State of Wisconsin attempted to subpoena their footage. “The state wanted any statement Steven made … and statements by others who might have knowledge or claim to have knowledge about who was responsible for the death of Teresa Halbach,” Ricciardi explained to BuzzFeed. “Our argument in trying to get the court to throw out the subpoena is that the state has access to all of this material. Steven is currently incarcerated. All of his calls, all of his visits are being recorded, so they don’t need to get that from us. It was a fishing expedition, and we really think it was an effort by the state to shut down our production. There was a way in which, on the one hand, Wisconsin is a very media-friendly state. It was great for us that cameras were allowed in the courtroom, it was great for us that they had a very expansive public records law so we could get the types of materials [we did]. On the other hand, the people on the ground, the people in power, weren’t always happy we were there.”

10. THE STAIRCASE INSPIRED THE EXTENDED FORMAT.

Though they originally envisioned the film as a documentary feature, the filmmakers quickly began to realize that—with all the twists and turns happening in Avery’s case—confining his story to a two-hour running time was going to be difficult. And it wasn’t until they saw the 2004 Sundance docuseries The Staircase that they realized a multi-part documentary was a possibility. “We were very interested in documenting the historical context for the new case,” Demos told Vulture. “It was then we realized the story could sustain a much longer form. There wasn't an outlet at the time that we really knew of. The one example there was was The Staircase, an eight-part documentary series on Sundance.”

11. BOTH PBS AND HBO PASSED ON THE PROJECT.

Three years after they first began production on the documentary, Demos and Ricciardi met with a number of network executives to discuss distribution, including representatives from PBS and HBO; all of them passed. It wasn’t until years later, in 2013, that Netflix optioned the series (they said yes based on seeing a rough cut of three episodes).

12. PROSECUTOR KEN KRATZ ISN’T A FAN OF THE SERIES.

Unsurprisingly, former D.A. Ken Kratz—who was part of the prosecution team that put Avery back behind bars—isn’t exactly a fan of the Netflix series, or his representation within it. “If you pick and choose and edit clips over a 10-year span, you’re going to be able to spoon-feed a movie audience so they conclude what you want them to conclude,” Kratz told Maxim. “That the theory of planted evidence ... is accepted by some people isn’t surprising at all. The piece is done very well, and I would have come to the same conclusion if that was the only material I was presented with.”

13. KRATZ CLAIMS THE FILMMAKERS LEFT OUT SEVERAL PIECES OF KEY EVIDENCE.

Netflix

In an interview with People, Kratz said the filmmakers left out and/or glossed over several pieces of evidence presented in court that he claims point to Avery’s guilt in the murder of Teresa Halbach, stating: “You don't want to muddy up a perfectly good conspiracy movie with what actually happened, and certainly not provide the audience with the evidence the jury considered to reject that claim.”

14. THE FILMMAKERS REFUTE KRATZ’S CLAIM.

In response to Kratz’s accusations, Demos told The Wrap that, “We tried to choose what we thought was Kratz’s strongest evidence pointing toward Steven’s guilt, the things he talked about at his press conferences, the things that were really damning toward Steven. That’s what we put in. The things I’ve heard listed as things we’ve left out seem much less convincing of guilt than Teresa’s DNA on a bullet or her remains in his backyard.”

“Ken Kratz is entitled to his own opinion, but he’s not entitled to his own facts,” Ricciardi added. “If he’d like to put together a documentary and try to discredit us in some way, he’s welcome to do that. We’re not going to be pulled into re-litigating the Halbach case with him.”

15. AVERY MAY NEVER SEE THE DOCUMENTARY.

Despite his cooperation, Avery may never get a chance to see Making a Murderer for himself. He has no access to Netflix streaming in prison and DVDs are prohibited, according to Dean Strang, who represented Avery during his murder trial.

16. IT MAY BE THE DIRECTORIAL DEBUT OF BOTH FILMMAKERS, BUT DON’T CALL THEM INEXPERIENCED.

When asked by Indiewire what the biggest misconception was about them and their work, the filmmakers were quick to respond: “That we don't have any experience. Over the past 10 years, we made the equivalent of five feature films.”

17. WHETHER OR NOT AVERY'S CASE WILL BE REVIEWED AGAIN IS UNKNOWN.

Netflix

Since Making a Murderer's Netflix premiere, worldwide interest in Avery's case—and whether or not he was wrongfully convicted a second time—has grown. In addition to a Change.org petition imploring President Obama to pardon Avery (there are more than 350,000 signatures and counting), a petition directly to the White House acquired more than 100,000 signatures, which prompted a response—though probably not exactly the answer that Avery's many advocates were hoping for. The White House stated that, "Since Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey are both state prisoners, the President cannot pardon them. A pardon in this case would need to be issued at the state level by the appropriate authorities." Still, the online hacktivist group Anonymous has taken up the cause and claims to have evidence that will exonerate Avery. If that's true, it's likely the only thing that would allow Avery's case to be reexamined: He has exhausted all his appeals.

“What ultimately freed him [before] was newly discovered evidence where the technology advanced to the stage where you could test the DNA,” said Avery's post-conviction attorney, Robert Henak. “In this case, we’re looking for technology to do the same kind of thing, to show that the evidence at the original trial really did not mean what the state was arguing that it meant and what the jury believed that it meant.”