Published in December 1843, A Christmas Carol took Charles Dickens just six weeks to write, during which time he wrote intensely and fanatically, only stopping to take occasional long walks through London in the early hours of the morning to clear his head. Less than two weeks after he completed it, the manuscript went to print; by Christmas Eve, the first 6000 copies had sold out.

Despite the early success, the publication of A Christmas Carol was far from smooth. After falling out with his publisher, Dickens funded the print himself to ensure all profits were his, but his insistence on top-quality paper and an expensive leather binding meant that the total cost of production was eye-wateringly high. From the initial 6000 sales, he made a profit of just £230 (around £29,885, or $39,560 today), having expected to earn closer to about four to five times that amount. Worsening his financial woes, the book was pirated by a rival publisher named Parley’s Illuminated Library two months later. Dickens sued, but in response Parley’s merely declared themselves bankrupt, leaving him to pay his own legal costs, which amounted to £700 (around £90,953/$120,376 today).

It may have had a rocky start, but A Christmas Carol soon established itself as one of Dickens’ most popular books, both with readers and its author alike. In fact, Dickens chose A Christmas Carol for his final public reading on March 15, 1870, just three months before his death. But what had inspired Dickens to write it in the first place?

1. A Charity Fundraiser

On October 5, 1843, Dickens spoke at a fundraising event at the Manchester Athenaeum, a local society engaged in promoting education in the city. At the time, Manchester was renowned across the world as one of the most important hubs of the Industrial Revolution, but its sudden growth had been at great social expense, and it’s believed that the strict utilitarian rules and poor pay imposed by factory owners on the city's workers inspired Ebenezer Scrooge’s own lack of charity and empathy—as he famously says, “Are there no prisons? … And the Union workhouses? Are they still in operation?”

2. The Town of Malton, North Yorkshire

Not long before beginning work on A Christmas Carol, Dickens vacationed in the town of Malton in Yorkshire. The town is said to have inspired a number of details in the book, including its numerous recurring references to church bells, which Dickens is believed to have modeled on the bells of Malton’s St. Leonard & St. Mary Catholic Church. In 2012, the town purchased a signed copy of A Christmas Carol from a collector in New York.

3. Charles Smithson

While in Malton, Dickens stayed with a friend named Charles Smithson, who worked as a solicitor there from offices on Chancery Lane—which is believed to have inspired Dickens’ description of Scrooge’s own counting-house. The two Charleses had met more than a decade earlier while Smithson was working at the London office of his family’s firm, when a friend of Dickens—for whom he was acting as guarantor—bought into the business. The pair remained close friends for the rest of their lives, even after Smithson returned home from London to Yorkshire.

4. “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton”

Dickens often had the characters in his novels tell their own stories and fables, and his debut novel The Pickwick Papers was no exception. In it, Mr. Wardle recounts a tale called “The Story of the Goblins Who Stole A Sexton” about “an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow” named Gabriel Grub, who is visited by goblins on Christmas Eve who try to convince him to change his ways by showing him images of the past and future. Sound familiar … ?

5. “How Mr. Chokepear Keeps a Merry Christmas”

“The Goblins Who Stole A Sexton” might not have been the only tale Dickens took his inspiration from. Two years earlier, in December 1841, a short story called “How Mr. Chokepear Keeps A Merry Christmas” appeared in the British satirical magazine Punch. Written by Douglas Jerrold, the story recounted in detail a Christmas Day celebrated by a businessman named Tobias Chokepear: He begins by having breakfast with his family, then attends church and enjoys a lavish Christmas lunch before “cards, snap-dragons, quadrilles, country-dances, with a hundred devices to make people eat and drink, send night into morning.” But despite apparently having a very merry Christmas, the story concludes by mentioning that a man Tobias had lent money to is now in a debtors’ prison; that one of Tobias’s daughters is absent from the Christmas feast, as she has been shunned by the family for marrying beneath her; and that while the Chokepear family celebrates inside, crowds of “shivering wretches” pass by their door. Although the uncharitable Mr. Chokepear doesn’t end up having the same Christmas epiphany as Scrooge, it’s likely that Jerrold’s moralistic tale had at least some influence on Dickens, not least because the two were well acquainted—when Jerrold died in 1857, Dickens served as a pallbearer at his funeral, and went on to donate the profits from one of his own short stories to his widow.

6. Washington Irving’s Sketch Book

Washington Irving’s Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., a collection of essays and short stories, was published more than 20 years before A Christmas Carol in 1819. Although its most famous story by far is "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," the Sketch Book also contains a number of festive tales and dissertations presenting an idealized image of Christmas, with gifts, decorations, songs, dances, games, and lavish spreads of food and drink. Irving partly based these descriptions on his experiences staying at Aston Hall, a stately Jacobean home on the outskirts of Birmingham, England. It’s believed that those descriptions, in turn, greatly influenced Dickens’ writing—in 1841, two years before he published A Christmas Carol, Dickens (who was just 8 when Sketch Book was published) wrote to Irving, “I wish to travel with you ... down to Bracebridge Hall.”

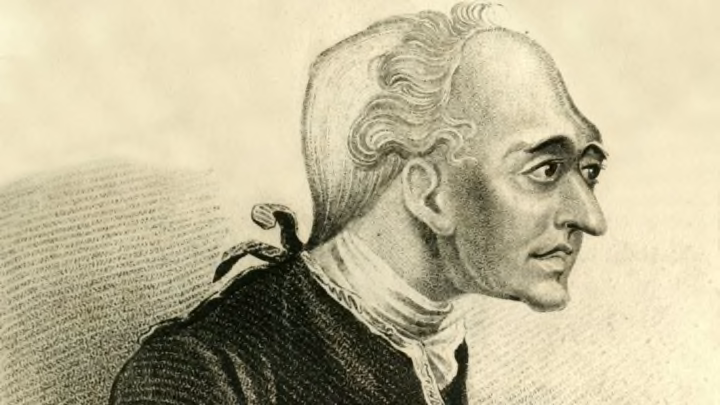

7. John Elwes MP

For Scrooge's miserly character, Dickens is believed to have turned to an infamously penny-pinching 18th century politician named John Elwes.

Born in London in 1714, Elwes inherited a fortune when his father died just four years later, and when his mother (who was so frugal that despite being wealthy she was said to have starved herself to death) died shortly after that, the entire Elwes estate—worth around £100,000—passed to him. Then again in 1763, Elwes’s entitled uncle Sir Harvey Elwes also died, and his even larger estate—worth more than £250,000—also passed to him.

He might have been enormously wealthy, but Elwes began priding himself on spending as little as possible. Despite being elected to parliament in 1772, he apparently dressed in rags, and often looked so shabby that he was mistaken for a beggar and handed money in the street. He only visited doctors when needed, and once after deeply gashing both his legs, he only paid the doctor to treat one—and wagered the doctor’s bill that the untreated leg would heal faster (he won by a fortnight). He let his vast houses become ruins through lack of repair; would go to bed as soon as the sun set to save buying candles; and would even eat molding food to save buying fresh (including once eating a dead moorhen pulled from a river by a rat—although that one is probably just an urban legend). Through all of his penny-pinching ways, Elwes left an estate worth at least £500,000 to his two sons when he died in 1789, having earned himself the nickname “Elwes the Miser.”

After his death, Edward Topham wrote a very popular biography of Elwes that went through 12 editions over the next several years. But Topham had his own reasons for writing Elwes' story; to him, Elwes represented “the perfect vanity of unused wealth.”

BONUS: One Person Who was Likely Not an Influence—Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie

According to legend, on a visit to Edinburgh in 1841, Dickens took a walk around the city’s Canongate churchyard and there happened to notice a gravestone bearing the unflattering inscription, “EBENEZER LENNOX SCROGGIE—MEAN MAN.” Dickens later wrote that it must have “shrivelled” Mr. Scroggie’s soul to take “such a terrible thing to eternity,” but it was nevertheless all the inspiration he needed to create the miserly character of Ebenezer Scrooge. Except that Dickens had misread the inscription. Born in Kirkaldy in 1792, Ebenezer Scroggie was actually a “meal man,” or corn merchant.

Here's the problem with this tale: That's probably all it is. A representative from the Edinburgh Civic Trust told Uncle John's Fully Loaded Bathroom Reader that it was an "interesting tale, but not necessarily based in fact ... [T]here is no evidence of an Ebenezer Scroggie as a merchant in the post office directories for the period, the grave conveniently no longer exists and there is no parish burial record. I’ve also yet to see where the direct quote from Dickens comes from."

So where did the myth come from? "I find myself complicit in a probable Dickens hoax," Rowan Pelling wrote in The Telegraph in 2012:

"On Monday, I was alerted to a letter in The Guardian, which claimed to know the source for the name Ebenezer Scrooge. The correspondent related how Dickens 'visited the Canongate churchyard in Edinburgh’s Royal Mile' in 1841 where he 'spotted a memorial slab to Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie, 'meal man’ (i.e. corn merchant).' Dickens is said to have misread this as 'mean man' and to have been impressed that a man could be so miserly that the trait was recorded for posterity. In the full version of this tale, Scroggie is revealed to have been a licentious bon viveur. How do I know? I published this literary 'exclusive' in 1997, in The Erotic Review. As we went to press, the facts were queried and it hit me that its author, Peter Clarke, was probably pulling my leg. No one could find any corroborating evidence, but it seemed a shame to let the facts obstruct a good yarn. The Edinburgh merchant’s fame has continued to spread: in 2010 it was reported that, although Scroggie’s gravestone had been removed in the Thirties, a new memorial was planned in honour of the man who inspired Charles Dickens. I await new developments with bated breath."

To find out more about the Christmas stories Charles Dickens published after A Christmas Carol, head here.

A version of this story ran in 2015; it has been updated for 2021.