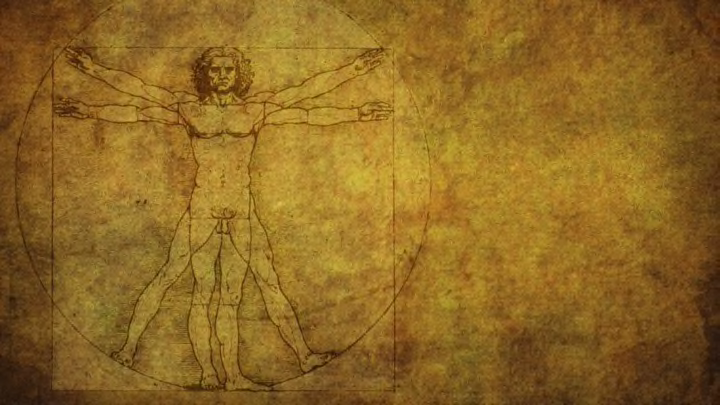

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man has evolved over the last five centuries from a thoughtful sketch into the picture of health. But the history behind this drawing is as curious as its image is omnipresent.

1. Leonardo never intended for Vitruvian Man to be displayed.

The sketch was discovered in one of the High Renaissance master's personal notebooks. The study was simply for the artist’s own edification, and when he completed it around 1490, he likely never expected it would be admired. Yet today Vitruvian Man is iconic and among the artist's best known works, along with The Last Supper and Mona Lisa.

2. It's art-meets-science.

A true Renaissance man, Leonardo was not only a painter, sculptor, and writer, but also an inventor, architect, engineer, mathematician and amateur anatomist. This pen and ink drawing was his exploration of the theories about human proportions set forth by ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. In his treatise De Architectura, Vitruvius wrote, "For if a man be placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a pair of compasses centered at his navel, the fingers and toes of his two hands and feet will touch the circumference of a circle described therefrom. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square figure may be found from it."

3. Leonardo was not the first to attempt to illustrate Vitruvius's theories.

American scholar Toby Lester explained to NPR in a 2012 interview, "Especially in the 15th century, in the decades leading up to Leonardo's own time in drawing, a number of people begin to try to render that idea in visual form."

4. It may have been part of a collaboration.

In 2012, Italian architectural historian Claudio Sgarbi shared findings that he felt indicated Leonardo's study of proportion was sparked by a similar one done by his friend and fellow Vitruvius-enthusiast Giacomo Andrea de Ferrara, an architect of the time. There's some debate about whether the pair worked in tandem, but even if this theory is incorrect, historians agree Leonardo perfected flaws in its execution where Giacomo failed, including the second set of arms and legs that allow for a more accurate depiction of Vitruvius's writings.

5. The circle and the square have a grander meaning.

In their mathematical explorations, Vitruvius and Leonardo were looking for not just the ratios of man but of all creation. In a notebook from 1492, Leonardo mused, "By the ancients man has been called the world in miniature; and certainly this name is well bestowed, because, inasmuch as man is composed of earth, water, air and fire, his body resembles that of the earth." In other words, man is a microcosm of the universe.

6. It's one of a series of sketches.

To improve his art and better understand how the world around him worked, Leonardo drew many people, marking off how their proportions fell.

7. Vitruvian Man is the male ideal.

The identity of the model remains shrouded in mystery, but art historians believe Leonardo took some liberties in his drawing. This work was not a portrait as much as a diligent depiction of a perfect male form designed by math, not shaped by life.

8. It could be a self-portrait.

Going off scant descriptions of the 15th-century artist as a younger man, some art historians have suggested Leonardo himself is his Vitruvian Man model. As Lester told NPR: "He was described as being very finely built, strong, very beautiful with locks of hair that curled and went down to his shoulders. There are a couple of possible renderings of him, one that survives in a sculpture from Florence and another that's in a fresco from Milan, and they both look a bit like that figure as well." But he admitted there's no way to know "for sure."

9. Vitruvian Man had a hernia.

That's the diagnosis that surgical lecturer Hutan Ashrafian made 521 years after the fact: An inguinal hernia. Ashrafian further theorized that such an issue could have killed this Vitruvian Man, and if Leonardo modeled the figure off of a cadaver, it was possibly the hernia that did him in.

10. You need the surrounding notes for the full context.

As the sketch originally appeared in a notebook, Vitruvian Man sat surrounded by handwritten notes regarding its observations about human proportion. Translated to English, they read in part: "Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by Nature as follows that is that 4 fingers make 1 palm, and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man's height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his buildings. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle. The length of a man's outspread arms is equal to his height." [PDF]

11. The body is striped with measurement lines.

Look at the man's chest, arms and face. Solid straight lines mark Leonardo's proportions, to which his notes refer. For instance, the ears/bottom of nose to the eyebrows make up a third of the face, while the bottom of the nose to the chin makes up the lowest third, and the eyebrows to the hairline make up the top.

12. It has other, less esoteric names.

The sketch is also called Canon of Properties or Proportions of Man.

13. Vitruvian Man strokes 16 poses.

At first glance, you might only see two: Standing feet together, arms outstretched and standing feet apart arms lifted. But part of the genius of Leonardo's depiction is that the superimposed body allows for views of 16 combinations of these outstretched limbs.

14. It has been co-opted for a political message.

Reconnecting to Vitruvian Man's relation of man and nature, large-scale artist John Quigley used the familiar image to illustrate the aggressiveness of global warming. Pictures of ice melting may not move mercury for many, but by constructing Melting Vitruvian Man on a massive ice floe in 2011, Quigley was able to give the issue a new scale. Quigley's copper strip sketch measures four times the size of an Olympic swimming pool.

15. The original sketch is rarely seen in public.

Recreations can be found far and wide, but the original is too fragile and important to be on permanent display. Vitruvian Man is typically kept under lock and key at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice. An exhibition held in 2013 offered the first chance in 30 years to see Vitruvian Man, and in 2019, the Gallerie put on a 3-month exhibition in honor of the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death. Any other time, the only way to view Leonardo's sensational sketch is to request special permission for a private session to the Office of Drawings and Prints.