Visitors to Chicago’s Field Museum will see a dinosaur named SUE, check out some of the earliest dioramas created by the visionary taxidermist Carl Akeley, and wander through an Ancient Egyptian tomb. But much of the museum’s collections—which contain some 30 million objects—are not on display. Earlier this year, mental_floss visited The Field Museum to take a peek at the institution's research collections; here are a few things we saw behind the scenes.

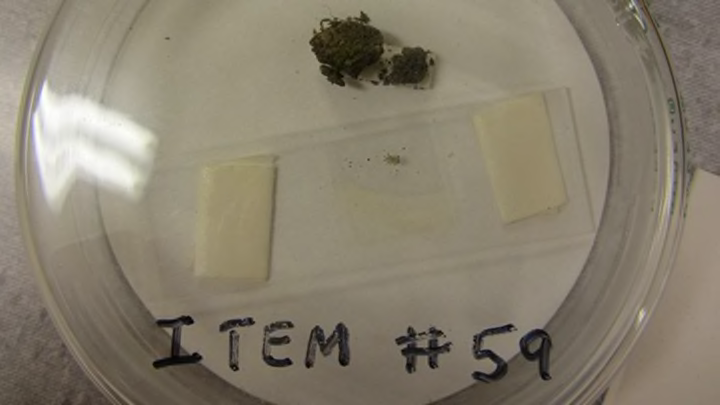

1. THE MOSS THAT HELPED CRACK A CRIMINAL CASE

Photo by Erin McCarthy

In 2009, two employees of Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip, Illinois, were accused of digging up bodies, dumping them in other locations around the cemetery, and reselling the plots. When authorities found 1500 bones from at least 29 people scattered around the grounds, the employees at first denied it, then changed their tune to say that yes, bodies had been dug up, but it had happened a long time ago. So the police called in experts from The Field Museum to weigh in.

“One of the things found was a clump of dirt that, according to the tag, was ‘found amongst human bone remains approximately 8 inches under the surface,’ and it had green moss growing on it,” said Laura Briscoe, a bryologist (someone who studies mosses) and collections and research assistant in the Botanical Collections. “The thought was, ‘Is this something that could be living underground and still be bright green, or was this evidence of something that was more recently turned under?’”

The team collected samples of the moss at the cemetery to prove it was growing there. Back at The Field Museum, they analyzed the moss specimen that the police had collected alongside the fresh moss they had gathered, then sent the fresh moss to physiologists that specialized in mosses. “We determined that the moss was probably not underground for more than two years,” Briscoe said.

Other scientists not affiliated with The Field Museum, working on tree roots found with human remains, reached the same conclusion. In February, the employees were found guilty. Now, the moss—evidence bag and all—is part of the museum’s Botanical Collections, which numbers some 3 million specimens.

2. SOUPED-UP SHREW SKELETONS

Scutisorex somereni skelton. Photo by Erin McCarthy.

Not all spines are created equal—and two species of shrew have the most incredible vertebral columns of all. The so-called Hero Shrew (Scutisorex somereni) was first discovered by Western scientists in Uganda in 1910 and in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1915. The locals, of course, had known about it for much longer. “They told the scientists, ‘If we take some of that animal’s hair, or we kill it and burn it in the fire, and smear the ash on our bodies, we will be invincible when we go into battle. We will survive any spear, any bullet,’” Bill Stanley, Director of Collections, Gantz Family Collections Center and Negaunee Collection Manager, Mammals, told mental_floss when we visited. (Stanley passed away on October 6 during an expedition in Ethiopia.)

The scientists were rightfully doubtful—and then one of the natives, a fully grown man, grabbed a live shrew, put it on the ground, and stood on top of it on one foot for 5 full minutes. When he stepped off of it, the animal walked away. “Anything else would have just been crushed flat,” Stanley said. Though scientists brought a specimen back to the United States, they wouldn’t discover the truly incredible thing about the animal until 1917: Its vertebral column, which has double the number of lumbar vertebrae of typical mammals. For example, typical mammals may have five or six compared to 11 in Scutisorex. The profuse development of interlocking spines—especially on the lumbar vertebrae (from 20 to 28) is a situation unrecorded for any other mammal. The spines are fixed so that the horizontal spines interlock with those of the next adjoining vertebra. “This is the most bizarre spine of any animal in the world,” Stanley said.

Scutisorex thori skeleton. Photo by Erin McCarthy.

Fast forward to 2012, when Stanley was in the Congo trying to track the vector in an outbreak of monkeypox. In the process of collecting animals and taking tissue samples, Stanley found a new species of hero shrew. “It didn’t have as many processes as the other hero shrew, and the processes were slightly bigger,” he said. “It was big news. This would be like finding a new species of platypus.” He named the new species Scutisorex thori. “While it might invoke the god Thor, it’s actually named after a personal hero, Thor Holmes, who is the collection manager of the Vertebrate Museum at Humboldt State University, where I went to school,” Stanley said.

Though scientists aren’t quite sure why these shrews have such intense spines, there is one hypothesis, offered by Stanley’s friend, Lynn Robinson, who went with villagers to an area where they collected beetle grubs from between the bark and trunk of palm trees. “The villagers said, ‘We always see hero shrews running around here,’ and Lynn thought to himself, ‘I bet the shrews crawl between that brack and the trunk, and they bend their backs and are able to pry the brack away from the tree and get food that isn’t accessible to anybody else,’” Stanley said. “We don’t have proof of this, but it is a hypothesis to explain the adaptive significance.”

3. FRANCIS BRENTON’S BOATS

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 190571

The Field Museum’s anthropology collection contains between 1.5 and 2 million objects; 800 are stored in a big climate- and temperature-controlled room deep underground, below the museum’s public halls. Among the things you’ll see in the room are Roman wine and oil storage vessels from the time of the Vesuvius eruption; a scaled-down Japanese pagoda built for the 1893 World’s Fair; and huge masks used in the ceremonial rites of the Sulka in Papua New Guinea. The room also holds Francis Brenton’s boats.

Born in Britain in 1927, Brenton eventually settled in Chicago. There, the photographer became a member of Chicago’s Explorers Club and made trips to Central America, bringing things back for The Field Museum. At one point, he took a trip down to Panama, where he acquired a 20-foot-long canoe from the Kuna people for the museum. To get it back to Chicago, “He had a second canoe, 2 feet longer than this one, lashed them together, and sailed them up to Chicago from Colombia—up the Mississippi, up the Illinois River, into Burnham Harbor,” said Christopher Philipp, Regenstein Collections Manager of Pacific Anthropology at The Field Museum.

One canoe became part of the collection; Brenton, meanwhile, took the other, put a fiberglass pontoon on it, and traveled out the St. Lawrence River to the Atlantic. From there, he attempted to sail all the way to Africa. “He got lost at sea, was picked up by a German freighter, and was eventually deposited in Senegal,” Philipp said. Then he hatched a plan to try to cross the Atlantic in a hot air balloon, starting in Cape Verde. When that didn’t work, he disposed of the pontoon, got another boat, and “sailed his vessel back across the ocean and to Chicago,” Philipp said. That boat also became part of The Field Museum’s collections.

Brenton would go out to sea again, and get lost again—this time, for good. “We don’t know what happened to Mr. Francis Brenton,” Philipp said. His boats, too, were lost for a time in The Field Museum itself, because they had no catalog numbers, which tie an object to the data about it. “Pre-1999, that used to sit out in the Middle American halls,” Philipp said. “All the paint was gone from the inside, because kids would hop in it for photo ops.”

When it came off display, some believed it was an exhibits prop and could be thrown out. “I was acting as a registrar for the department in 1999 and found the accession file for this thing and said, ‘We can’t throw that out!’” he recalled. They identified Brenton’s other boat from the Senegalese flag painted on it.

4. CRYOLOPHOSAURUS BONES

It might be hard to tell, but this is a dinosaur skull. Note the crest on the top right of the skull, from which the animal gets its name: Cryolophosaurus, or frozen crested lizard. Photo by Erin McCarthy.

The geological history of Antarctica isn’t exactly clear. “Most of it is under ice, so a lot of what we know is what has been spit up by glaciers,” said Peter Makovicky, an associate curator in the Earth Sciences section at The Field Museum. “It wasn’t until Robert Falcon Scott’s expedition in 1912, when he found Glossopteris [seed fern fossils], that it became clear that this place has a deep geological history.”

Then, in 1990, a geologist walking up Mount Kirkpatrick—part of the 14,000-foot-high Central Transantarctic Mountains—stumbled across a dinosaur thigh bone, purely by chance. (It wasn't the first dinosaur fossil to be found in Antarctica: Those were unearthed on the Antarctic Peninsula in the 1980s; the animal they came from, an armored dinosaur, wouldn’t get its scientific name, Antarctopelta oliveroi, until 2006.) A group of paleontologists also working on the continent began to extract the dinosaur from the side of the mountain 12,000 feet above sea level. “They got the skull and a number of parts in 1990,” Makovicky said. By 1994, it had a name—Cryolophosaurus, or frozen crested lizard, which lived at the beginning of the Jurassic and was “sort of the first big dinosaur and predator,” Makovicky said. “It’s from 195 million years ago. Dinosaurs were present in the Triassic, but they shared their environment with a lot of other animals. At the beginning of the Jurassic, dinosaurs were the big dogs on the block—and this is sort of the first big meat eater.”

The scientists returned to the site in 2003, and Makovicky was part of the last expedition there, in 2010 and 2011. Getting to the site involves helicoptering in, and the researcher had to use power tools to extract the fossils. “The fossils come from mudstone,” he said. “It’s extremely hard and virtually unbreakable.” Typically, the next step would be to wrap the bones in plaster to secure them for their trip to The Field Museum, but in Antarctica, that’s impossible—the water in the plaster freezes before the fossils can be wrapped. So the scientists extracted huge hunks of rock containing the bones, dragged them to the helicopter landing zone for a flight back to camp, then loaded them onto big military planes, which then flew the specimens back to McMurdo. There they were eventually loaded on cargo ships and taken back to The Field Museum.

The holotype specimen at The Field Museum is about half of the animal. The mountainside where it was found “is actually pretty rich with dinosaurs,” Makovicky said. On the most recent trip, “we found parts of a small plant-eating dinosaur”—one of three different herbivores found on the mountainside, which has yet to be named—“and another Cryolophosaurus brain casing.”

Analyzing the vascular structure of a juvenile dinosaur. Photo by Erin McCarthy.

Once back at museum, preparers used tools to isolate the bones from the rock. Scientists at the museum are now studying these dinosaurs, examining the bones, using 3D printers to print the skulls and analyze brain casings, and slicing open the fossils to look at the vascular structures inside under microscopes.

5. KIWI FEATHER CLOAK FROM NEW ZEALAND

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 273650

In 1958, the museum acquired around 9000 Pacific Island objects from a London-based collector named Alfred Fuller, who bought the objects from traders at auction. “He wasn’t really out to collect the most beautiful things, or the aesthetic objects," Philipp said. "He was looking for the range of technology. So there will be 18 fish hooks from Tonga, and they’ll all be a little different, technology-wise. But there are also many beautiful objects in the collections as well.”

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 273650

One of the beautiful things is this cloak, made from the feathers of kiwi on a backing of flax with a tāniko border. These cloaks are still made by Maori women today, and are given to both men and women of high status. The Maori also see these historical objects as connections to their ancestors. “When I held my first visit to this cabinet with a Maori weaver, she started crying as soon as I opened the cabinet,” he said. It wasn’t because the cloak was in bad condition—it’s not—but because of the connection she felt with her ancestors who made the garment. “It really highlights the importance that The Field Museum has in keeping and caring for these objects,” Philipp said. “They aren’t just things that you stick up on the wall to display.”

6. FIJIAN CLUBS

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 274251

Star Wars fans might find these clubs familiar: According to Philipp, creator/director George Lucas based the weapons carried by the Tusken Raiders on the Totokia—top-heavy wooden clubs carried by Fijian warriors in the 1800s. The clubs were used in warfare to deliver a deadly blow to the skull. They've also been called pineapple clubs.

7. SHARK-TOOTH SPEARS

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 91440

The Field Museum has 123 weapons, spears, or lances that feature shark teeth from Kiribati. The weapons, which line the walls of the Anthropology Oversize storage room, come from two main sources: A 1905 acquisition from a German supply house called the Umlauff Museum, and the 1958 acquisition from Fuller. (Fun fact: To protect themselves against these nasty weapons, warriors would wear armor woven with coconut fiber and human hair.) And they’re proof of how historical research collections can inform current science.

A few years ago, Josh Drew, who was working in the ichthyology department, came down to the anthropology collections and asked if there were any shark tooth weapons from the Gilbert Islands, which are part of the Republic of Kiribati in the central Pacific Ocean. “We’ve got a lot,” Philipp said. After looking at all 123 of these weapons, Drew determined that three of the shark species represented on the weapons are no longer present in the waters near the Gilbert Islands.

“That opens up many questions,” Philipp said. “Was it overfishing? Was it global warming? Was it trade between ancient islanders? We don’t know the answers to those questions. But here’s really old historical objects informing current science, which is really cool, and shows you the reason why we keep all this stuff. Lots of people come down here and say, ‘Why do you keep this stuff if it’s not on display?’ Well, this is primarily a research collection. We don’t know what we’re going to be able to do with collections 100 years from now.”

8. DRAWINGS BY CHRISTOPHE PAULIN DE LA POIX DE FREMINVILLE

Photo by Erin McCarthy

The Field Museum has around 7500 volumes in its Mary W. Runnells Rare Book Room, but it also has plenty of things that aren’t books. Among its 3000 works of art are the graphite drawings and watercolors of Christophe Paulin de la Poix de Freminville, who was born in 1787 and died in 1848. The collection was purchased and donated to the library in 1990s.

Freminville was a sailor in the French Navy and did a lot of traveling. “He went to the North Pole and the Caribbean,” said technical services librarian Diana Duncan. “There are several species that bear his name, but most of his published works deal with antiquities, so he was an archaeologist, too.”

Photo by Erin McCarthy

The Field Museum has several boxes of drawings and matted works from Freminville. He drew everything from snakes to butterflies to fish. Many of them never made it into books—which, sadly, isn’t all that unusual. “There are some publication endeavors that people work on and they run out of money, or they die, and their dreams go unrealized,” said Christine Giannoni, the museum’s librarian. “There’s all sorts of sad stories in the history.” It's not known why Freminville failed to publish these remarkable illustrations.

9. THE BOWL THAT SOLVED THE MYSTERY OF MAYA BLUE

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 189262.1&.2

Archaeologists have long been interested in Maya Blue, a pigment that’s been used on everything from murals to ceramics. “Maya blue has always been kind of an enigma because it’s a very stable pigment,” said Gary Feinman, MacArthur Curator of Mesoamerican, Central American, and East Asian Anthropology. “It’s one of the few blues that’s produced without any modern chemical processes. It was made pre-Hispanically—the Maya and Mesoamerican people figured it out.”

How they made the pigment was a mystery—until scientists analyzed an incense-burning bowl that had been dredged from a cenote, or sinkhole, in Chichen Itza in the late 1800s. The piece, which was initially held at Harvard, was traded to The Field Museum in the 1930s (“at that time,” Feinman said, “it was OK to trade pieces”). The bowl still contained copal incense, a type of tree resin. “The incense, which is an organic material, normally would not preserve in an archeological context," Feinman said. "But it was preserved because it was underwater for centuries.”

Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 189262.1&.2

Dean Arnold, who became an adjunct curator at The Field Museum after he retired from Wheaton College, “has been investigating Maya Blue forever,” according to Feinman. When he wanted to continue his research into the pigment, he came to The Field Museum, which has a laboratory that allows researchers to analyze the chemical compositions of substances. One of the pieces they pulled for testing was the bowl. They examined the copal and eventually took a sample, which they analyzed with a mass spectrometer.

“We noticed that there was something interesting about this particular piece of preserved copal because there’s blue pigment on it,” Feinman said. “It also has white inclusions, which turned out to be a very fine white clay.” Using the test, they surmised that Maya Blue was made in a process that used resinous copal as a bonding agent to fuse the inorganic molecule (fine white clay) to an organic molecule (indigo solution). “The inorganic material is a fine clay and the organic material is a solution of indigo, which gives the pigment its blue color,” Feinman said.

This approximately 1100-year-old figurine head, which has a lot of Maya Blue on it, "comes from a late classic Maya site in the northern part of the Maya region," Feinman said. "It looks like it could be an important figure, given the nature of the jeweled headdress, but more than that I cannot say. This was almost certainly a part of a full-body figure, but the rest is gone." Photo by Erin McCarthy // The Field Museum, Cat. No. 48592.

The scientists concluded that the Maya were likely making Maya Blue at the edge of the cenote, coating objects (or human sacrifices) with the pigment, and then throwing them into the water. “A 16th-century Spanish priest who studied the Maya and Maya sacrifice reported that everything, when it was sacrificed, was first painted blue, so they were making the pigment on the side of the cenote before they sacrificed and threw it into the water,” Feinman said. “It gave us the first context ever where the Maya were actually making Maya blue. In other words, we know they made it at various places, but here we have proof that they were making it at the side of the sinkhole. There’s a good chance that they were using this copal incense and heat , because they burned the copal as a resin to bind the indigo solution and the clay. Those two things don’t fuse easily, but once they do, it’s a very stable bond.”

10. A BOOK THAT BELONGED TO ONE OF THE SIGNERS OF THE CONSTITUTION

Photo by Erin McCarthy

At some point in his life, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney—signer of the Constitution, Revolutionary War vet, presidential candidate, and buddy of Alexander Hamilton—nabbed himself a copy of Philosophie Botanique de Charles Linné and signed his name on the title page. “He signed it as an owner,” Giannoni said. “There are bookplates—which would say ‘this book belonged to so and so’—but other people would sign their names as a mark of ownership.” The library purchased this volume in 1907.

11. PEREGRINE FALCON EGGS

Photo by Erin McCarthy

Most of the bird egg collection at The Field Museum is more than 100 years old. Back then, the collection and study of eggs—called oology—was a popular pursuit. People would go to active nests, pull out eggs, remove the insides, and add them to their collections. But no more. “It’s just not a cool thing to do anymore like it was back in the day,” said Joshua Engel, a research assistant at The Field Museum.

Still, the egg collections are another example of how historical specimens can inform scientific research much later. In the 1960s and ‘70s, ornithologists noticed that apex bird populations were declining. Eventually, the entire Midwestern population of Peregrine Falcons was wiped out. “One big problem was that eggs weren’t surviving the nests—they were breaking really easily,” Engel said. The scientists went into museum collections, at The Field Museum and around the world, where they analyzed contemporary eggs against historical ones, looking at things like weight and thickness of the shells. “They were able to determine that egg shells were much thinner during that period, especially in the ‘70s, than they were before,” Engel said. The culprit? Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, a pesticide widely used on crops after World War II. The use of DDT was banned in the United States in 1972.

To bring Peregrine Falcons back to the Midwest, scientists worked with falconers to breed birds for release into the wild. Peregrines typically nest on cliffs, and the hope was that the reintroduced birds would return to their historic range. Many Peregrine instead build their homes on skyscrapers, using the urban environment like a pseudo-cliff. The Chicago Peregrine Program started 30 years ago and has grown since then from none to “just a couple of birds to 30 pairs through the state of Illinois,” Engel said. “When you’re talking a big bird of prey, that’s a big number.”

These days, the scientists keep close tabs on the birds. “We go to the nests in late spring, take the young birds out, and put bands on their legs,” Engel said, so that birders can track them. And if they go to a nest and find some unhatched eggs, they’ll take them, blow out the insides, and add the shells to the collections: “You never know how they’ll be used down the line.”

12. THINGS MADE FROM PLANTS DATING BACK TO THE WORLD COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION

Photo by Erin McCarthy

The Field Museum’s Economic Botany Collection contains “everything from musical instruments to drinking vessels to baskets—things people make out of plants,” Briscoe said. There are jars of baby pineapples preserved in liquid, dried-out loofahs, drawers full of tea, and, delightfully, container upon container of plant-related items from the World Columbian Exposition of 1893. Among them is a jar labeled “Croton Draco? Dragon’s Blood” that came from Colombia. Dragon’s Blood is a cure-all medicine made from the latex (sap) of a tropical South American croton plant, used to treat about any ailment internally and externally.