The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 205th installment in the series.

October 12-13, 1915: Germans Execute Edith Cavell, Bomb London

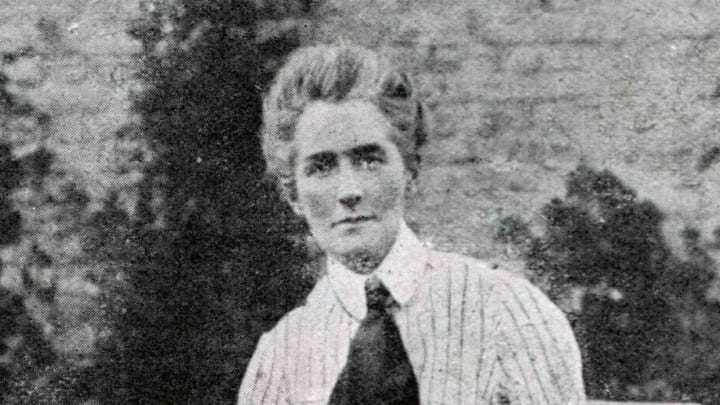

The execution of Edith Louisa Cavell, a British nurse who helped Allied prisoners of war escape Belgium, provided yet more evidence (if any more were needed after Belgian atrocities, Louvain, Notre Dame de Reims, the Lusitania, and gas) that the men in charge of the German war effort had no grasp of the propaganda struggle being waged alongside the shooting conflict, pitting them against the Allies in a battle for the high ground of global public opinion.

A devout Anglican, Cavell had worked in Belgium teaching nursing beginning in 1907, and bravely returned from London after war broke out to continue ministering to wounded soldiers from both sides at her clinic in Brussels. In addition to her life-saving work, Cavell was apparently contacted by British intelligence agents who prevailed on her sense of patriotism to help smuggle around 200 Allied soldiers out of Belgium to the Netherlands, for eventual repatriation; she also passed information to the Allies, concealed on the bodies or in the clothes of the escapees.

Apprehended on August 15, 1915, along with 34 others Cavell was charged with treason by authorities of the German military occupation force in Belgium (despite the fact that she had neither German nor Belgian citizenship, common conditions for a charge of treason). Because Cavell was already well known for her charitable work, her arrest spurred immediate appeals from clemency.

Pleas from the U.S. and Spanish ambassadors failed to move the German military authorities in Belgium, and Cavell was executed by firing squad at 2 a.m. on October 12, 1915, along with her co-conspirator Philippe Baucq. Her final words to an Anglican chaplain who was allowed to visit her reflected her unwavering idealism and Christian piety: “Standing as I do in view of God and eternity, I realise that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

There was no question of Cavell’s guilt (she confessed) and both sides of the conflict had already shown their determination to take extremely harsh measures against spies (or even suspected spies, probably leading to the deaths of scores of innocent people). Nonetheless executing Cavell was a self-inflicted propaganda defeat, as it played into popular narratives of passive female victimhood and uncomplaining Christian martyrdom dating back to the Victorian era.

The international outcry over Cavell’s death prompted the Germans to commute the death sentences of the 33 surviving conspirators, but the damage was done: the execution of Cavell soon became symbolic shorthand for German brutality and “frightfulness.”

Many ordinary Germans realized that killing Cavell was a mistake, at least according to the German novelist Arnold Zweig. In his novel Young Woman of 1914 one of the characters, Sergeant Brümmer, remarks mournfully to the heroine Lenore Wahl:

We shall have to pay for that girl’s blood, and it will take a great many lives to avenge it. They tell me that the English newspapers are wild about it. Why were these people allowed to shoot a brave young woman because she helped prisoners to escape over the frontier… She wasn’t just an ordinary girl she was a nurse, Fraulein Wahl. And she worked in a hospital where she looked after a great many of our men, both officers and rank and file. I needn’t tell you the story in detail, but it’s the talk of all Belgium, and indeed the whole world just now.

Significantly Zweig’s characters seem to share the same Victorian attitudes toward female virtue that made Cavell the perfect tragic victim in British and French eyes:

Lenore sat with wandering eyes, ready for flight. She remembered the Archduchess, the first victim of this war. Shot in Serajevo; and now another woman too—shot in Brussels. Had not all the thinkers in Germany, and indeed in all the world, conferred on women their charter of humanity? Couldn’t she have been pardoned, or even imprisoned? This was too much…

Conversely sentiment wasn’t necessarily unanimous on the Allied side, as some men objected to the special status accorded her as a female victim. A few weeks after her execution Frederic Keeling, a British soldier on the Western Front, noted that his comrades weren’t much impressed by the self-righteous rhetoric:

I see from the papers that the silly sentimental agitation about Nurse Cavell still goes on at home. A good many soldiers out here don’t think much of it. I have discussed it with many and found them all of my opinion—while admiring the woman immensely, I think the Germans were quite within their rights in shooting her. The agitation reveals the worst side of the English character. I hope some Suffragists who prefer to stand for the principle of women’s equal responsibility for their actions will protest against the rot that is being talked.

Bloodiest Zeppelin Raid of the War

On the night of October 13, 1915 German zeppelins struck Britain yet again, in what turned out to be the bloodiest bombing raid of the war carried out by airships (though not airplanes). This time five zeppelins—L11, L13, L14, L15, and L16—bombed London and several surrounding towns, killing 71, including 15 Canadian soldiers, and wounding 128. Once again the raid rattled British civilians and made an especially big impression on children. One boy, J. McHenry, wrote about the bombing of London the following day for school, describing what were obviously ineffective air defenses:

I had not been reading more than half an hour when I heard a terrible bang… I dropped the book, rushed to the window opened it and jumped out into the parapet… No sooner had I got out when bang – bang two more bombs followed in quick succession, and then all was silent for a few seconds. Boom—crash—boom, came the answer from our guns, and a hail of lead went sailing skywards, but I am sorry to say that they did not find their destination. I could see gun flashes coming from the British Museum and from the Kingsway, I only just caught a glimpse of the zeppelin in the city direction the search-lights were shining on it, and the shells were bursting underneath it. Whether it was hit I do not know but all of a sudden It disappeared and fled.

See the previous installment or all entries.