The ocean is full of incredible creatures vying for our attention. The Rare Book Room at the American Museum of Natural History is giving them the spotlight they deserve, with a collection of old, exquisitely illustrated tomes dedicated to the study of those animals. The imagery from the books—and the historical research that goes along with them—is featured in Opulent Oceans, the third part in a series dedicated to rare works found in the museum's library.

“For Opulent Oceans, I wanted to cover as many groups of ocean animals and plants as possible,” author and curator of Ichthyology Melanie Stiassny told mental_floss. “The first thing I did was compile a list of all of the main groups of organisms that live in the oceans. It was a long list—from tiny copepods to giant whales, and from algae to sea urchins!—but once I had my list I began looking for beautiful images featuring representatives of as many of those groups as I could find in the Rare Book collection.”

Stiassny included plenty of well-known scientists, from Charles Darwin to David Starr Jordan, but says she was introduced to many others during her time in the library. “The museum’s collection of rare books is amazing—a real hidden gem of the place,” she says. “Even though I have worked here for ages, I have never before been able to spend so much time wandering the stacks. It really was a very special treat to discover the works of so many marine pioneers.”

Stiassny says she learned a lot in her research for Opulent Oceans, but the most exciting discovery, she says, “was the understanding that although much has changed since those pioneering years of marine biology, most of those changes are just the technological accoutrements of modern science—Global Positioning Systems, deep sea submersibles, computers, and cameras. What remains the same is the sheer excitement of exploration and the joy of discovery.”

An exhibition of artwork from Opulent Oceans, curated by Stiassny and Tom Baione, the museum's Director of Library Services, is currently on display outside the museum’s LeFrack Theater through October 2016; you can buy the book here.

1. VAMPIRE SQUID

AMNH/R. Mickens

This illustration of Vampyroteuthis infernalis—which literally means “vampire squid from hell”—appeared in French professor Louis Joubin’s 1920 book Resultats des Campagnes Scientifiques accomplies sur son yacht par Albert 1er Prince Souverain de Monaco. These denizens of the deep sea, which grow to be about 11 inches long, have reddish-brown skin and large blue eyes that can reach 0.9 inches in diameter—the largest eye-to-body ratio of any animal in the world.

2. DARWIN’S BARNACLES

AMNH/R. Mickens

Five years before he published On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin published a four-volume work on his other obsession: barnacles. A monograph on the sub-class Cirripedia, with figures on all of the species, featured these large acorn barnacles (Megabalanus tintinnabulum) which are believed to be native to the tropics, but have since spread all around the world by attaching themselves to the hulls of ships.

3. DOLPHIN

AMNH/R. Mickens

This woodcut, from the 1555 book La nature & diversité des poisons, avec leurs pourtraicts, representez au plus près du naturel by French explorer and naturalist Pierre Belon, features a not-quite-accurate member of the dolphin family, Delphinidae. The dolphin was so fanciful that Stiassny wasn’t able to pinpoint what species it was. “Often the names used for many of the organisms depicted in the older works have changed over time, so it required a bit of detective work to try and decipher what species they may actually represent,” she says. “In a few cases it simply wasn’t possible—like Belon’s lovely dolphin—but in most cases the illustrations were so accurate that I was able to track down what species they actually were.”

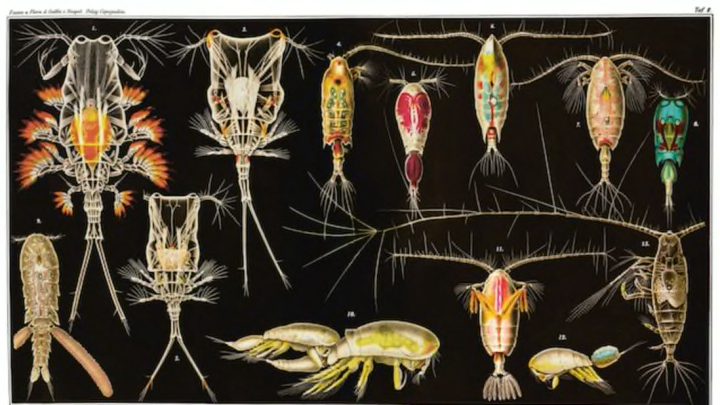

4. GLOWING COPEPODS

AMNH/R. Mickens

When it came time to illustrate these tiny bioluminescent crustaceans in his 1892 book Systematik und Faunistik der pelagischen Copepoden des Golfes von Neapel…, German zoologist Wilhelm Giesbrecht chose to put them on a dark background—not unlike the dark ocean environment they call home. According to the BBC, some copepods “discharge packets of bioluminescent liquid whose flashes are delayed and go off like depth charges,” which confuses their predators and allows them to get away.

5. HAWKSBILL TURTLE

AMNH/R. Mickens

In his book Historia testudinum iconibus illustrata, published between 1792 and 1801, physician and naturalist Johann David Schopf described 33 different kinds of turtles and tortoises—including this Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricate), which today is a critically endangered species. The turtle was illustrated by Friedrich Wilhelm Wunder, who worked from Schopf’s drawings.

Fun fact: As juveniles, Hawksbill turtles have heart-shaped shells, which get longer as they grow older.

6. SIPHONOPHORES

AMNH/R. Mickens

French naturalist and explorer Francois Peron collected these marine siphonophores for his 1807 book Voyage de decouvertes aux terres australes. Some of these fragile creatures can grow to be 100 feet long.

7. KING RAGWORM

AMNH/R. Mickens

One thing Stiassny didn’t find, despite really trying, was a female scientist to feature in Opulent Oceans. “The period covered in the book was a time of deep and pervasive hostility to the active participation of women in science,” she says. But she was able to feature an image drawn by a woman, and it’s one of her favorite images in the volume: the drawing of the magnificent king ragworm (Alitta virens) from William Carmichael McIntosh's A monograph of the British marine annelids. McIntosh, who found the worm on a beach, brought it home alive for his sister, Roberta, to draw. “After her death, McIntosh dedicated his life’s work to her, describing her as his ‘fellow worker and artist,’” Stiassny says. “Although her scientific acumen went unrecognized by the scientific establishment of the day, at least her brother fully appreciated her contributions.”