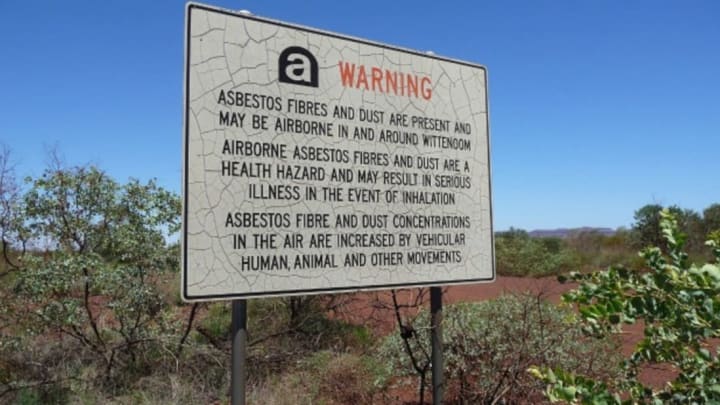

Welcome to Wittenoom, Australia, where the weather is beautiful, the scenery is unparalleled, and toxic substances seep from the earth.

Located in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, Wittenoom was once one of the top blue asbestos mining locations in the world, causing families to flock to the area for jobs. Also known as crocidolite asbestos, blue asbestos was a valuable commodity used for fire protection in ceiling tiles, insulation, electrical work, battery casings, and more. But it was also an incredibly dangerous one—all types of asbestos can cause fatal illnesses, but because crocidolite fibers are as thin as a strand of hair, they’re easily inhaled and may be responsible for more deaths than any other type of asbestos. In Wittenoom—where workers once held asbestos-shoveling contests, and families thought it safe to let their kids play in the stuff—thousands of former residents have died from asbestos-related causes.

Five Years via Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

The mining industry in Wittenoom was halted in 1966, not necessarily for health reasons, but for economic ones—the company which owned the mines was $2.5 million in debt. Health concerns weren’t really addressed until the late ‘70s, when the government started taking steps to shut the town down completely. Buildings were demolished, the airport was closed, and residents were urged to leave. By 1992, less than 50 citizens remained, and by 2007, it was down to eight. Today, just three brave souls still call Wittenoom home.

Why would three people stay in a town that’s still riddled with cancer-causing materials, a town with no electricity or water, one that has literally been erased from maps by the government because of the danger it poses? They all have different reasons.

Peter Heyward, a resident for more than two decades, stays for the nature and the “silent stillness” of the surroundings. “The hills, the plains, the openness, the quiet. I love the country," he told Australia's The Age in 2007. Since so many buildings were razed, he now has a perfect view of Hamersley Mountain Range.

Mario Hartmann stays put largely because he was unimpressed with the amount of money the government offered to buy him out—$40,000 plus $10,000 in moving costs: “What can you buy with $40,000? They'll have to offer $400,000, what it takes to buy a house somewhere else.”

This year, Lorraine Thomas, a 30-plus year veteran of Wittenoom, told WA Today she refuses to let the potential presence of asbestos scare her away. "It's only the dust that's dangerous," she said, a threat she believes has dissipated after the mines' closures. An official report begs to differ, calling the risk to tourists (of which there are still up to 40 a day) and residents alike "extreme."

Neither Thomas nor her fellow residents have any illnesses relating to the asbestos that still looms large in the area.

For a closer look at the ghost town's holdouts—filmed when there were still eight people residing there—the short documentary Wittenoom is worth a watch:

Wittenoom from Caro Macdonald on Vimeo.