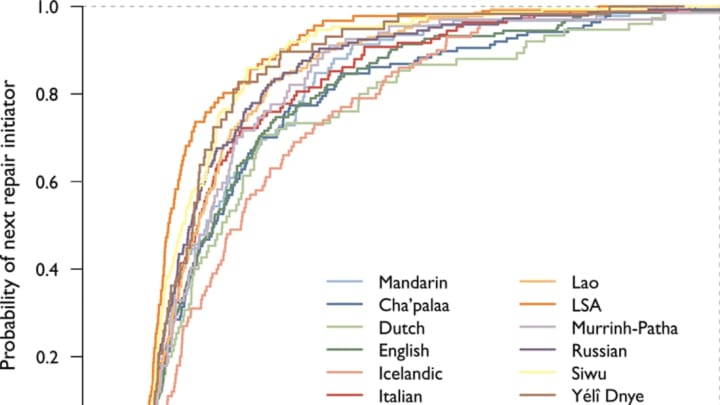

Huh? Who? What? These kinds of little questions that ask for clarification are so pervasive in conversations that we barely notice them. But they are asked, on average, every 84 seconds. So finds a new study by Mark Dingemanse, Nick Enfield, and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics of video-recorded informal conversation in 12 languages. The languages covered a wide range of language types, from English and Italian to Yélî Dnye (a language isolate from Melanesia) and Argentinian Sign Language. In all of the individual conversations recorded (about 48.5 hours total), after one of these little questions has been asked and answered, another such "repair sequence" took place within six minutes.

What do these repair sequences look like? Across all languages in the study, the questions that came up in repair sequences fell into three types. Let’s say you are talking to a friend, and because of background noise or a distraction you completely miss a whole phrase. In that case, you are sure what you missed, so you would use an open-ended question like Huh? (A previous study by Dingemanse found that all languages seem to have a form close to Huh? for this purpose.) If you only missed a specific word or piece or information, you would ask a more specific question like What time? And if you just want to make sure you heard a specific piece of information correctly you would ask for confirmation of what you understood as in She had a boy?

The first type of repair requires the least amount of effort on your part and the most on the part of your friend, who has to repeat the whole missed phrase. The other two types require increasingly more effort on your part and less effort for your friend.

Over the conversations analyzed, these repair types were used in a systematic way that supports the idea that there is a universal inclination to create the least amount of work for both participants, not, selfishly, just for the one asking for clarification. When possible, the more specific questions are used, and this was true for a whole range of languages. This tendency appears to be uniquely human. While other animals do have ways of dealing with the problem of ensuring that a message gets through, they are costly, involving lots of repetition, redundancy, and energy. The study shows how our system is geared toward efficiency and cost-savings and reveals, according to Dingemanse, “the fundamentally cooperative nature of human communication.”

When it comes to sound, word structure, sentence structure, and meaning, the world’s languages differ in myriad ways. But at the level of conversational interaction, where problems are spotted, pointed out, and dealt with, there is a notable similarity between very different languages. This reveals, Dingemanse writes, “a common infrastructure for social interaction which may be the universal bedrock upon which linguistic diversity rests.”