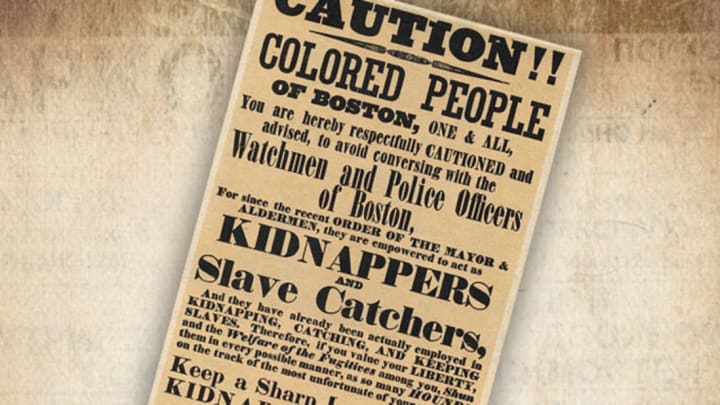

Today, September 18, marks the anniversary of one of the most infamous laws in United States history: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The law, which obligated U.S. citizens to turn in suspected runaway slaves even if they lived in free states, was intended to pacify pro-slavery states and dissuade them from leaving the Union.

The Fugitive Slave Act didn’t save the country from descending into war with itself, of course. What it did accomplish was a decade-long reign of terror. Denied the right to a jury trial, accused runaways—including free blacks who’d never been enslaved—were helpless to defend themselves against their accusers’ claims.

The demise of the law began not with the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, however, but at the start of the Civil War. An archaeological excavation in Hampton, Va. recently shed new light on a little-known event that helped close this chilling chapter of American history.

Oral tradition and historical documents indicated that land in downtown Hampton had been a refuge for escaped slaves during the Civil War. But no archaeological work had ever been undertaken on the site, which most recently housed an apartment complex (it was demolished in 2012).

Last year, the City of Hampton funded a preliminary excavation. It didn’t take long for the archaeologists to uncover a treasure trove: old fence lines, remnants of trash pits, and evidence of pit cellars embedded in a deeper layer of clay.

“There were literally dozens and hundreds of those things,” says Matt Laird, a partner and senior researcher at the James River Institute for Archaeology, which performed the excavation. “There was evidence of garbage pits that looked like they were filled with artifacts from that time period.”

Artifacts unearthed from the site. Image credit: courtesy of The James River Institute for Archaeology

So what did this site have to do with the demise of the Fugitive Slave Act? In the first weeks of the war, three enslaved men took a desperate, dangerous chance on freedom by requesting sanctuary at Fort Monroe, a Union fortification, even though personnel were still obligated to uphold the Fugitive Slave Act.

General Benjamin Butler, Fort Monroe’s commander and a former lawyer, was sympathetic to the men’s plight. He came up with a clever circumvention to the law by declaring the escaped slaves “contraband” that might be used to support the rebel cause, effectively creating a path to asylum.

Word soon spread, and Fort Monroe received hundreds of slaves seeking protection under the new contraband policy. Thousands ultimately settled in nearby fields and burned-out Hampton homes as white residents fled and Confederate forces, fearing a Union takeover, torched the town. The site buried beneath the now-demolished apartment complex is believed part of what came to be known as the Grand Contraband Camp.

An 1864 image of the Grand Contraband Camp. Image Credit: Library of Congress

Today, the remnants of the camp provide a glimpse at the historical moment when the Fugitive Slave Act began to die and one of the first free African-American communities in the South rose up in its place.

“It’s fascinating to see this in a Southern stronghold, right in the middle of Confederacy," Laird says. "You have black neighborhoods with street names like Liberty and Union."

The camp was precedent-setting. Soon, escaped slaves established similar camps throughout the South under the protection of Union troops. None were as extensive as the original, and most were temporary. By contrast, the Grand Contraband Camp evolved into a thriving community that helped rebuild the city after the war.

Laird would love to sift through the trash pits and start piecing together a picture of daily life for camp residents who eked out a living from virtually nothing. But the city of Hampton only funded a preliminary excavation of the site—just enough data to pique the curiosity of archaeologists and residents, some of whom are descendants of the Grand Contraband settlers.

Laird hopes the city can find funding to continue, but knows the site could be sold to a developer. He notes that Hampton will mark its 400th anniversary in 2019, around the same time Virginia’s first slaves arrived in Hampton. He’d like the site to be part of that commemoration.

“Here’s the example of slavery being introduced to Virginia at the very beginning, then you have the Contraband Camp at the end of slavery, and one of the first free black communities,” he says. “To honor that would be interesting.”