The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 201st installment in the series.

September 14, 1915: Prelude to Rebellion

Just as the passage of the Home Rule Act in May 1914 seemed about to bring the longstanding controversy over Irish self-government to a head, external events unexpectedly intervened. With the outbreak of the First World War the whole issue of Irish autonomy was moved to the back burner by the British government with the Suspensory Act of September 1914, justified on the grounds that now was not the time to proceed with a major reorganization of the state.

This delay was supposed to last just one year, until September 18, 1915, but the changing political landscape threatened to make it permanent. In the spring of 1915 the crisis in British munitions production led to the “Shell Scandal,” which forced Prime Minister Herbert Asquith to form a new coalition government including members of the opposition. One of the key figures in the new cabinet was the Ulster Unionist Edward Carson, who as a Protestant bitterly opposed Irish Home Rule and demanded continued “Union” with the rest of Britain.

Carson joined the cabinet as Attorney General of England and Wales, giving him considerable influence over domestic policy; meanwhile the Irish Nationalist Party led by John Redmond, which represented Irish Catholics demanding Home Rule, was the only parliamentary party not included in the coalition.

Following this political realignment, it came as no surprise when the cabinet issued an Order in Council renewing the Suspensory Act on September 14, 1915, just a few days before it was due to expire – deferring Irish Home Rule for the duration of the war (which everyone now realized would probably last for years).

Moderates Eclipsed

As the British government reneged yet again on its promises of Irish Home Rule, discontent was mounting rapidly among Irish nationalists, many of whom now turned their backs on the policy of peaceful legislative change advocated by moderates like Redmond, and embraced more radical (meaning, violent) solutions.

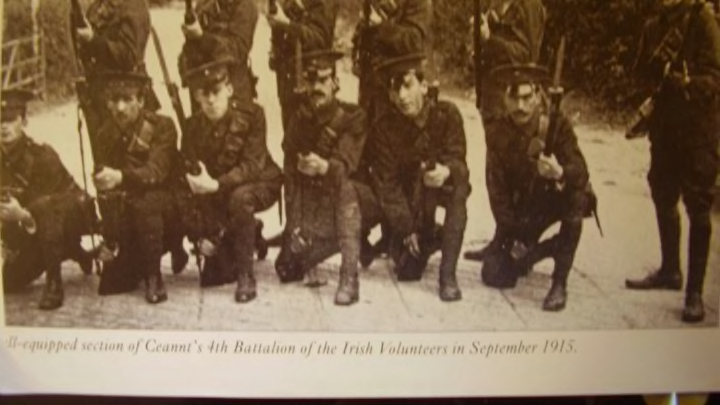

Even before the cabinet renewed the Suspensory Act, in May 1915 the radical nationalist leader Thomas Clarke had secretly formed the Irish Republican Brotherhood Military Council, which would be responsible for organizing the failed Easter Uprising in April 1916. The IRB Military Council would coordinate the activities of the Irish Volunteers (top), a paramilitary led by Patrick Pearse that seceded from John Redmond’s National Volunteers (below) over the issue of service in the British Army, and the smaller Irish Citizen Army led by James Connolly.

By fall 1915 British intelligence was well aware that rebellion was brewing in Ireland. In one secret report filed in November (which, like many Irish people, mistakenly identified the rebels as belonging to the nationalist organization Sinn Fein) British agents warned that the advent of conscription, then under debate, might trigger an uprising: “This force is disloyal and bitterly Anti-British and is daily improving its organisation… its activities are mainly directed to promoting sedition and hindering recruitment for the Army and it is now pledged to resist Conscription with arms.”

Indeed, the preparations were more or less open in many parts of Ireland, as ordinary people made no secret of their hostility to Britain – even to the extent of shunning their own family members who served in the British Army. Edward Casey, a “London Irish” (Irish Cockney) soldier in the British Army, recalled a visit to his cousin’s family in Limerick in the company of a priest in mid-1915:

He took me in[to] the house without knocking, and when my Aunt (who is a widow) saw us together, [she] said in her deep Irish Limerick brogue: “And what in the name of God are you bringing into my house? A British soldier! And I’m telling you Father, he is not welcome.”… The atmosphere in the room was very chilly… It was a very anxious time for me. They were the only Relations I have known. But they accepted me, as a relation.

Later Casey and his cousin visited a pub, the latter telling him on the way:

“I feel very sorry for you. The Germans are going to win this War, and we (us Sinn Feiners, both Men and Women) will do all we can to help.”… He then made a little speech telling his friends who I was, and finished with the words, “Blood is thicker than water, and like someone said on the Cross, “we forgive you, ye know not what ye do.”… When one man, asked Himself who the hell I was, Shamas repeated, “This is my first cousin from London. He is my Mother’s Sister’s Boy. And I’ll have you treat him with respect. If you don’t, I’ll ask you all to come outside and take your coats off and fight.”

Another Irish soldier serving in the British Army, Edward Roe, also recalled the rebellious mood prevailing in Ireland during a visit home in July 1915:

What a change of sentiment since 1914. Home Rule had not materialized; there was a dread of conscription; even my friend Mr. Fagan (Tom the Blacksmith) had turned pro-German and cheers for the ‘Kaizar’ [Kaiser] when leaving the village pub at ‘knock out.’ The ‘Peelers’ [police] have threatened to jail him several times, but he still defies them.

Conflicts Behind the Front

Although armed rebellions like the Easter Uprising were relatively rare, the First World War exacerbated ethnic tensions and stoked nationalist movements across Europe, presenting yet another challenge to governments which found themselves grappling with angry dissidents on the home front at the same time as foreign enemies abroad.

This was especially true in Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia – polyglot empires ruled by dynastic regimes which dated back to the feudal era, and were ill-equipped to deal with the competing demands of their rival nationalities.

In Austria-Hungary Emperor Franz Josef sat uneasily on the two thrones of his divided realm as the Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, trying to steer a common military and foreign policy with mixed results. Meanwhile both the Austrian Germans and Hungarian Magyars were pitted against the Dual Monarchy’s numerous minority nationalities, including the Italians, Romanians, and various Slavic peoples (including Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenes, Poles, Slovenians, Croats, Bosnian Muslims, and Serbs). Indeed it was Franz Josef’s desperation to neutralize these centrifugal nationalist movements that precipitated the First World War.

Unsurprisingly nationalist resentments were rife within the ranks of the Habsburg armed forces. As early as September 1914 Mina MacDonald, an Englishwoman trapped in Hungary, recorded a Slavic military doctor’s gleeful prediction: “I assure you, whichever way it goes, it’s the end of Austria: if the Central Powers win we become simply a province of Germany: if they lose, it’s the disintegration of Austria. A country composed, as Austria is, of so many races, each one more discontented than the other, must not risk going to war.”

For their part at least some Austrian Germans had already given up on the idea of a multinational empire altogether, instead embracing the pan-German ideology first espoused by George Schönerer in the late 19th century and later by Adolf Hitler. Bernard Pares, a British observer with the Russian Army, recalled meeting a Habsburg prisoner of war in mid-1915:

There was one very militant Austrian German, who would have it that Austria would win; he was so rude about the Austrian Slavs that I asked him at the end whether Austria wanted the Slavs. He said they wished to be quit of Galicia, and in fact of all their Slav provinces; I suggested that Austria proper and Tirol might find their rightful place inside the German empire; he answered with alacrity, “Of course, far better under Wilhelm II.”

Similar tensions afflicted the Russian Empire, memorably described by Lenin as a “prison house of nations,” which ruled non-Slavic or ethnically mixed populations in Finland, the Baltic region, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Even when the subject peoples were also Slavic, as in Poland, nationalist feeling often fueled resentment of the “Great Russians” who ruled the empire – and this feeling was certainly reciprocated.

In January 1915 a Russian soldier, Vasily Mishnin, casually noted of the Polish inhabitants of Warsaw, part of the Russian Empire for a century: “The crowd seeing us off are not our people, they are all foreigners.” And in August 1915 another British military observer, Alfred Knox, noted the dilemma faced by a Polish aristocrat who didn’t want to abandon his estate to the approaching Germans: “Many officers sympathised with the poor landowner who had been our host. He wanted to remain behind, but Colonel Lallin, the Commandant of the Staff, spoke to him brutally, telling him that is he remained behind it would simply prove that he was in sympathy with the enemy.”

The Armenian Genocide, precipitated by the Christian Armenians’ support for the invading Russians, was only the most egregious example of ethnic conflict in the decaying Ottoman Empire. The Turks also expelled around 200,000 ethnic Greeks during this period, resulting in widespread misery among refugees temporarily housed on Greek islands (eerily foreshadowing the migrant crisis unfolding now), as recalled by Sir Compton Mackenzie, who described the encampment on Mytilene in July 1915:

There was nowhere one could walk but a small emaciated hand would pluck at one’s sleeve and point mutely to an empty hungry mouth. Once a woman dropped dead on the pavement in front of me from starvation, and once a child. No street was hot enough to dispel that chill of death. There were, of course, many organized camps; but it was impossible to cope with this ever increasing influx of pale fugitives.

Although Muslim Arabs fared somewhat better than the Armenians or Greeks under Ottoman rule, they remained politically and socially marginalized, stoking bitter resentment against the Turks among Bedouin nomads and townspeople alike. Ihsan Hasan al-Turjman, a young, politically aware middle class Palestinian Arab living in Jerusalem, wrote in his diary on September 10, 1915 that he would rather die than be drafted to fight the British in Egypt, decisively (if privately) renouncing his Ottoman identity along the way:

However, I cannot imagine myself fighting in the desert front. And why should I go? To fight for my country? I am Ottoman by name only, for my country is the whole of humanity. Even if I am told that by going to fight, we will conquer Egypt, I will refuse to go. What does this barbaric state want from us? To liberate Egypt on our backs? Our leaders promised us and other fellow Arabs that we would be partners in this government and that they seek to advance the interests and conditions of the Arab nation. But what have we actually seen from these promises?

Ironically some British troops, who understood Britain’s Irish troubles well enough, had a hard time grasping that their foes faced similar internal tensions. A British officer, Aubrey Herbert, remembered trying to convince ANZACs at Gallipoli that some captured enemy soldiers really wanted to collaborate with the invaders: “It was a work of some difficulty to explain to the Colonial troops that many of the prisoners that we took – as, for instance, Greeks and Armenians – were conscripts who hated their masters.”

Allied Hatreds

Internal ethnic tensions were only part of the picture, as traditional national rivalries and prejudices continued to divide the nations of Europe – even when they were on the same side. Although the war forced Europe’s Great Powers into marriages of convenience, which official propaganda did its best to portray in rosy terms of popular sympathy and mutual admiration, reality tended to fall rather short of this warm embrace.

For example, there was no getting around the fact that many British and French people simply disliked each other, as the always had (and still do). Indeed, while Brits of all classes sympathized with their French allies and paid tribute to their bravery, there was no question these feelings existed alongside traditional less flattering images, rooted in a millennium of warfare and colonial competition and reinforced by a cultural inferiority complex – and the French, despite their gratitude and affection for some British institutions, fully reciprocated this resentment and scorn.

One common British stereotype was that the French were incompetent when it came to warfare. Mackenzie recalled the contempt felt by the British officers at Gallipoli for their French colleagues in the Corps Expeditionnaire d'Orient:

It would be absurd to believe that the General Staff credited French G.Q.G. at Helles with as much military ability as themselves. They did not. They regarded French fighting much as Dr. Johnson regarded a woman’s preaching. Like a dog walking on his hind legs it was not done well, but they were surprised to find it done at all. The French and English were never intended by nature to fight side by side in joint expeditions.

The ordinary rank and file British soldiers seemed to share these views, and many French civilians made no secret of their dislike for the British. The novelist Robert Graves recalled an honest conversation with one young French peasant woman in the small village where he was billeted: “She told me that all the girls in Annezin prayed every night for the War to end, and for the English to go away… On the whole, troops serving in the Pas de Calais loathed the French and found it difficult to sympathize with their misfortunes.”

Typically the Brits, famous for their lack of interest in foreign ways, made little effort to bridge the obvious linguistic or cultural gap. On September 5, 1915, Private Lord Crawford complained in his diary about the lack of British translators: “It is a pity we can’t find officers of our own who can talk French well enough – but the linguistic ignorance of our officers is positively phenomenal.”

It’s worth noting that even within the British Empire, linguistic differences reinforced national prejudices and colonial resentments; thus one anonymous Canadian stretcher-bearer confided in his diaries, “I hate the very sound of the English accent.” In fact sometimes communication was almost impossible. Edward Roe, the Irish soldier, described his mystification at the rural accents he encountered in the English countryside while on leave in October 1915:

I go for long walks on Sundays and visit country pubs, and listen with amusement to country yokels talking in their quaint accent about cows, sheep, oats, cabbages and boars. I could not understand them, as they seem to speak a language all their own. One Sunday… I got into conversation in a pub with a bewhiskered old farm labourer. The subject we “were on” was sheep. I could only reply in yes’s and no’s… I could not understand a word of what he said.

An anonymous ANZAC soldier recorded a similar mix of disdain and incomprehension for rural English folk: “Our camp lay within two miles of Bulford village… inhabited by a bovine-looking breed, whose mouths seemed intended for beer-drinking but not talking – which, in a way, was just as well, for when they did make a remark it was all Greek to us.”

For their part troops from the British Isles found their peers from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand alarmingly undisciplined. Roe noted of some Australian convalescents who shared an English hospital with more reserved British counterparts:

They are a wild, devil-may-care lot and have upset the discipline of the whole hospital… Some are minus an arm and some a leg. They broke out into town the second night they were in hospital. Legs or no legs, arms or no arms, they scaled a 12 foot wall, set Devonport on fire and got uproariously drunk. It took the whole crew of a super-dreadnought in combination with the Military Police to shepherd them back to hospital… They do not understand discipline as it is applied to us.

Seething Central Powers

These tensions paled in comparison to the mutual antipathy between the Germans and Austrians, fueled by the Germans’ contempt for Austrian fighting prowess following the disastrous defeats in Galicia in the early part of the war, complemented by Austrian resentment of German arrogance, which only grew with the German-led victories after the breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow in May 1915.

These attitudes were shared by elites and ordinary people alike. In the fall of 1914 the anonymous correspondent who wrote under the name Piermarini recalled a deliberate social snub at the Berlin opera: “… [I]n front of me were two Austrian officers, while at my side some German people were discussing the war. They were speaking loudly about the battle in Galicia, and passed many untactful remarks, evidently meant to be heard by the Austrians. They carried this to such a length that the two officers left their seats and walked out.” The German author Arnold Zweig, in his novel Young Woman of 1914, recalled the bitter tone in spring 1915: “In every German beer-house men sat and jeered at these feeble allies, and the increasing reinforcements that they called for – which now amounted to entire German armies.”

The Austrians returned the German contempt with interest. In September 1915 Evelyn Blucher, an Englishwoman married to a German aristocrat and living in Berlin, noted in her diary:

The chief subject of discussion is the feeling between Austria and Germany… One cannot help being slightly amused to notice how the point of the whole war is forgotten in the greater interest of internal jealousies. I asked Princess Starhemberg one day whether there was much hatred against England in Austria. “Well, when we have time to, yes, we do hate them; but we are so busy hating Italy and criticizing Germany that we don’t think of much else at present.”

The dislike translated into a social gulf between German and Austrian officers, even when on foreign assignments where they might be expected to fraternize, if only because of their shared tongue. Lewis Einstein, an American diplomat in the Ottoman capital Constantinople, noticed the frigid relations between the “allies” there: “It is odd how little the Austrians and Germans mix. At the Club each sit at separate tables, and not once have I seen them talking together… The Germans make their superiority felt too much, and the Austrians loathe them.”

At least the Germans and Austrians in Constantinople had one thing in common – their complete disdain for their Turkish hosts, which Einstein also noticed: “It is odd to see with what scorn both Germans and Austrians talk of the Turks… If they do this as allies, what will it be afterward?” Of course the Turks, sensing more than a whiff of racism in these attitudes, weren’t shy about sharing their opinions of their esteemed guests. On June 23, 1915, as fighting raged at Gallipoli, Einstein noted: “There are more reports of growing ill-feeling between Turks and Germans. The former complain that they are sent to attack while the Germans remain in safe places. ‘Who ever heard of a German officer being killed at the Dardanelles?’ a Turkish officer asked… From the provinces as well come reports of the same ill-feeling.”

See the previous installment or all entries.