When Titian Ramsay Peale II died on March 13, 1885, the 85-year-old went to his grave believing that his life’s greatest work—a book describing the butterflies and moths of North America—would never be published. And for more than a hundred years, that seemed to be its destiny. But now, 130 years after his death, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) has finally printed portions of The Butterflies of North America, Diurnal Lepidoptera: Whence They Come, Where They Go, and What They Do, which Peale spent five decades working on, through tragedy and hardship, right up until his death.

“It became apparent to me, after poring over his manuscript and his paintings, that [Peale] was the original American lepidopterist,” David Grimaldi, curator of the Division of Invertebrate Zoology at AMNH, said at an event for the book. “He was working before any of the other Americans who are credited with being the early American lepidopterists. He just never published his work.”

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The son of famed naturalist, portraitist, and Philadelphia Museum founder Charles Willson Peale, Titian was born on November 2, 1799 and named after a brother who had died the year before at age 18. The two had more in common than just a name: Like the first Titian, Peale devoted himself to lepidoptery, the study of butterflies and moths, which he took an interest in from childhood. Both Titians were also gifted artists. “He followed very closely in his older brother’s footsteps,” Grimaldi said, “and was very proud of that, in fact.”

But he was more than a lepidopterist: Peale was an accomplished artist who received his first professional commission—creating plates for Thomas Say’s American Entomology, a work Grimaldi called “one of the first original American works on entomology”—when he was just 16. He would later contribute 10 plates to American Ornithology, written by Napoleon’s nephew, Charles Lucien Bonaparte.

Peale was also an explorer, traveling with Say to Florida and Georgia—“wild and wooly places” at the time, said Grimaldi—and working as an assistant naturalist on the Stephen Harriman Long expedition to the Rocky Mountains, the first government-sponsored scientific trip to the American west since Lewis and Clark. Later, he traveled to Suriname, Colombia, and Brazil to expand the collections of what by then had come to be called the Peale Museum, which he took over with his brother, Benjamin, when their father died in 1824.

Still, lepidoptery was Peale’s true passion, and by 1931, he was working on a proposal for a book that he called Lepidoptera Americana: Or, Original Figures of the Moths and Butterflies of North America: In their Various States of Existence, and the Plants on Which They Feed, Drawn on Stone, and Coloured from Nature: With Their Characters, Synonyms, and Remarks on their Habits and Manners. The book would have 100 hand-colored lithographs. Peale’s plan was to release four plates every two months, beginning as soon as possible.

All he needed were subscribers. According to Tom Baione, director of the Department of Library Services at AMNH, “At that time, scientific works were often, but not exclusively, published with the help of subscribers. So if you could find enough people who would agree to purchase the book, then you could proceed and perhaps produce some extras that could be sold to additional interested buyers.”

Unfortunately, only 27 people signed up for Peale’s book—far below the number he’d need to begin sending out folios. He continued to work on the book anyway.

©AMNH/D. Finnin

In 1838, Peale embarked on what Grimaldi called “probably the most adventurous exploration of his life,” as one of the naturalists on the United States South Seas Surveying and Exploring Expedition, the first seagoing expedition sponsored by the U.S. government. “[The expedition] went all along the Eastern coast of the New World, up along the West coast of South and North America, out to the Hawaiian islands, to the Galapagos, Fiji, and New Zealand,” Grimaldi said.

During the four-year trip, Peale identified and collected specimens of about 400 new species of Lepidoptera—which he then lost, along with his notes and private library, when the expedition’s ship, the Peacock, wrecked off the coast of present-day Portland, Ore., in 1841.

Things were about to get worse. Much, much worse.

Peale returned from the expedition to find that his Lepidoptera collections, which had been in storage awaiting a move to the Academy of Natural Sciences, had been destroyed in a fire. Then, the Philadelphia Museum—his family’s museum—closed permanently. Saddest of all, he lost his wife, a son, and a daughter, one right after the other.

“All through that difficult time,” Grimaldi said, “lepidoptera were the things that engaged him and brought him solace.”

©AMNH/D. Finnin

By the time he was 48, Peale realized that he was not going to be able to make a living on the study of lepidoptery or selling his art. So in 1848, he took a job as an assistant examiner at the United States Patent Office in the Division of Fine Arts and Photography in Washington DC. “He became a pioneer in photography,” Grimaldi said, but he didn’t slow down work on the butterfly book he still hoped to have published, “even though he had a means to much more quickly capture, with fidelity, these beautiful specimens. He continued to paint, continued to collect, continued to study and observe life history stages.”

At one point, Peale proposed “a way to facilitate publication [of his book] ... using photography, but which would really compromise the quality of the work,” Grimaldi said. “But he still couldn’t find backers.”

It was also during this period that the men that most consider the early American lepidopterists began to publish. One was William Henry Edwards, a wealthy West Virginia coal mine owner. “[He] was obsessed with butterflies,” Grimaldi said. “He bankrolled gorgeous illustrations of his own lepidoptera of North America, which was published between 1868 and 1872, in various folios.” Another was Herman Strecker, a stonemason who specialized in making memorial monuments for children and published Lepidoptera: Rhopaloceres and Heteroceres in 1872. Peale knew and corresponded with both—Williams even bought 50 of the specimen boxes Peale used to display his butterflies—and, says Grimaldi, both were probably well aware of Peale’s proposed book, thanks to his prospectus.

“I wouldn’t doubt that William Henry Edwards and Strecker rushed to get their stuff done so that they wouldn’t be beaten by Peale,” he said.

Peale—who had remarried in 1850—spent 25 years at the patent office, rising to the position of principal examiner. When he retired in 1873, he moved his family back to Philadelphia, where they lived with one of his grandsons and used his wife’s small inheritance to get by. The Academy of Natural Sciences agreed to give Peale a room to complete his book, which by then he had begun to call Butterflies of North America. He spent the rest of his life devoted to butterflies, collecting, raising, and studying them.

When he died in 1885, after being ill for just a day, his book still wasn’t complete. It nearly died with him.

©AMNH/D. Finnin

Peale’s manuscript remained in the family until 1916, when the nephew of Peale’s wife donated the book to the American Museum of Natural History. It was composed of 160-odd plates and 145 pages written on legal-sized paper.

The lepidopterist had made his paintings on heavy paper using mainly gouache paints, with additions made in watercolor, ink, and pencil. “Peale laid out the pages as he hoped they would be pictured in the book,” Baione said. “The name of the plate, and even the plate numbers, are all penciled in, in his neat hand.” Rather than repainting a butterfly’s life stages on a single page, Peale often cut and pasted life stages from previous paintings onto other pages. In many plates, Peale painted a solid background representing the sky—solid blue, gray, or streaked with pink and orange, denoting dusk or dawn.

After its donation, The Butterflies of North America became part of the museum’s rare book collection, where it was accessed by artists and art historians over the years, according to Baione. “I hate to disparage [Peale’s] scientific efforts,” he said, “but in the art world, Peale is better known.”

There the book remained until last year, when the project to publish Peale’s book began. The photography of the manuscript was supervised by AMNH conservation manager Barbara Rhodes. “My main role,” she told mental_floss, “was in handling the material for the photographer, so we could be certain that things would stay where they were supposed to and he didn’t expose them to too much light. A number of [the illustrations] do have loose components, so that was a consideration.”

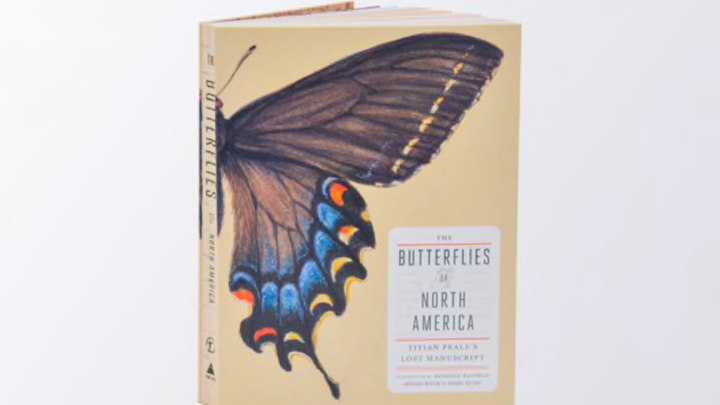

The resulting book, titled The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript, has three sections: the butterfly album, which includes all of the plates from Peale’s book and 14 of the original 145 manuscript pages; reproduced pages from Peale’s prospectus; and a section on a separate work of Peale’s called Lepidoptera: Larva, Food-Plant, Pupa, &c., which features the larvae of different butterflies and moths. Readers will find many butterflies they recognize within the book’s pages, like the Tiger Swallowtail, and some they might not, like Urania sloanus, a butterfly native to Jamaica that has since gone extinct.

And that's not all the museum has planned for Peale's work—there's also a grant proposal to re-treat it. The plates had been contained in a scrapbook until 1977, when it was disbound and taken to a bookbinder, who removed the paintings and secured them to artist’s drawing paper. The paper has curved a bit in the years since. Re-treating will “involve taking the paintings off of the artist’s paper,” Rhodes said. “Fortunately they’re not stuck overall, they’re just dots on the corners, so we think we can get them off reasonably easily and expeditiously. We don’t know if there’s any writing on the backs of these. It’s possible that there is and it just wasn’t documented in 1977. The documentation for this is fairly sparse.”

Rhodes has already made a box especially for Peale's work—a common practice at AMNH—and she plans to rehouse the paintings and repair the leather-bound scrapbook that contains the manuscript. “It’s still in the original cover, but it’s falling apart, unfortunately,” Rhodes says. “So we’ll fix that.”

Thanks to the efforts of Grimaldi and Baione and others at AMNH, Peale is finally getting his due. His story is a sad one, Baione said, “but it has a happy ending. The happy ending is today—his work and his reputation are resurrected.”