A recent study offers cat lovers some brand new ammunition in the endless “cat vs. dog” debate. According to this research, the arrival of felines had a bigger, and more devastating, impact on North America’s dog population than did climate change.

The dog family first appeared around 40 million years ago, possibly in modern-day Texas. Over time, three main subgroups arose: the extinct Borophaginae (meaning "bone-crushing dogs"), Hesperocyoninae ("evening" or "Western dog"), and the still-living Caninae (which includes wolves, foxes, and domesticated dog breeds). Around 28 million years ago, this dog diversity peaked, with almost 30 species roaming North America.

But then the Hesperocyoninae started dying out, and they completely disappeared about 15 million years ago, seemingly outcompeted by the faster, bigger, bone-crushing dogs. But the latter group faced stiff competition itself from some relatively new arrivals on the scene: cats. And in the end, the cats bested them.

That's the conclusion scientists from Sweden, Switzerland, and Brazil came to after examining more than 2200 North American carnivore fossils, about 1500 from 120 canine species, and another 744 from 115 other carnivore species, including bears, bear-dogs, and cats. Their findings were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Around 18.5 million years ago, primitive cats crossed the Bering Strait and arrived in Canada. Just three million years later, as felids started to become numerous across North America, the Borophaginae population took a nosedive. Borophagines went completely extinct more than 2 million years ago.

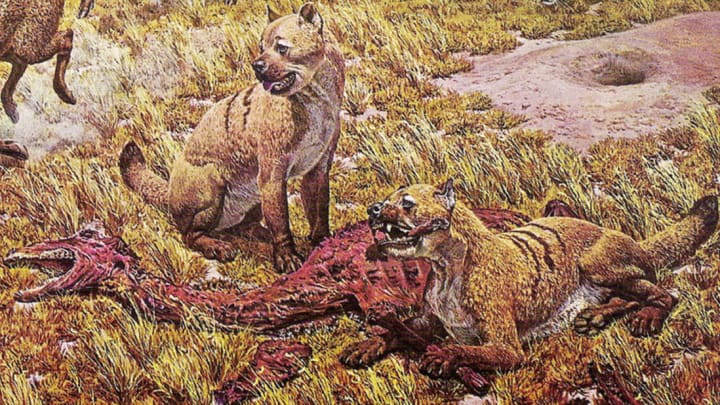

As study lead author Daniele Silvestro explains to mental_floss, this probably wasn’t a coincidence. Several Borophaginae species had a body structure that somewhat resembles that of a big felid more than that of a dog, Silvestro notes. Like cats, they could rotate their palms upwards, a useful adaptation for grabbing prey. They were also likely ambush predators in the vein of mountain lions or tigers. Because of these similarities, Borophagines and felids competed within many of the same niches.

But these early cats may have been better hunters, an edge that could have helped drive up to 40 dog species into extinction over the course of the approximately 15 million years the groups competed. (Unlike their bone-crushing relatives, members of the Caninae family, which began flourishing around 10 million years ago, weren’t especially affected by feline invaders. With their slender builds, canine dogs were, by and large, designed to run down their meals across great distances.) Based on the analytical models the researchers tested, Silvestro thinks this competition drove the eventual extinction of bone-crushing dogs above all other factors, including environmental and climate shifts.

When one group of organisms supplants another, evolutionary scientists characterize it as "passive replacement” if the new arrivals don’t take over until some external factor kills off the first bunch. A good example is mammals and dinosaurs. When Earth was dominated by dinosaurs, mammals already existed but were not very diverse or abundant because dinosaurs were using most of the resources. It was only when dinosaurs finally perished that mammals diversified and thrived, becoming Earth’s dominant land animals.

In the case of North America’s cat-and-dog saga, it looks like “active displacement” by cats did the dogs in. Advantage: cats.